Huge’ results raise hope for cancer breakthrough

In early results from a clinical trial, genetically engineered T cells eradicate leukemia cells and thrive. Two of three patients studied have been cancer-free for more than a year.

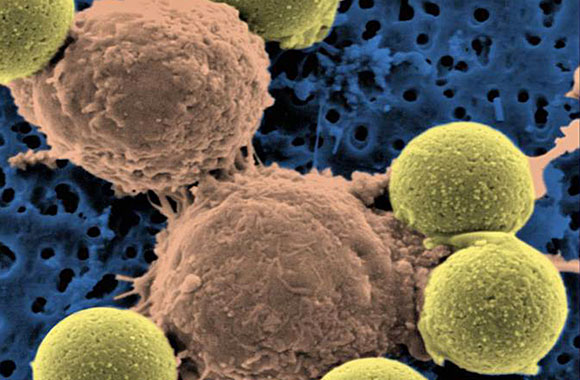

A microscopic image shows two T cells binding to beads, depicted in yellow, that cause the cells to divide. After the beads are removed, the T cells are infused into cancer patients. (Dr. Carl June / Penn Medicine)

In a potential breakthrough in cancer research, scientists at the University of Pennsylvania have genetically engineered patients’ T cells — a type of white blood cell — to attack cancer cells in advanced cases of a common type of leukemia.

Two of the three patients who received doses of the designer T cells in a clinical trial have remained cancer-free for more than a year, the researchers said.

Experts not connected with the trial said the feat was important because it suggested that T cells could be tweaked to kill a range of cancers, including ones of the blood, breast and colon.

“This is a huge accomplishment — huge,” said Dr. Lee M. Nadler, dean for clinical and translational research at Harvard Medical School, who discovered the molecule on cancer cells that the Pennsylvania team’s engineered T cells target.

Findings of the trial were reported Wednesday in two journals.

To build the cancer-attacking cells, the researchers modified a virus to carry instructions for making a molecule that binds with leukemia cells and directs T cells to kill them. Then they drew blood from three patients who suffered from chronic lymphocytic leukemia and infected their T cells with the virus.

When they infused the blood back into the patients, the engineered T cells successfully eradicated cancer cells, multiplied to more than 1,000 times in number and survived for months. They even produced dormant “memory” T cells that might spring back to life if the cancer was to return.

On average, the team calculated, each engineered T cell eradicated at least 1,000 cancer cells.

Side effects included loss of normal B cells, another type of white blood cell, which are also attacked by the modified T cells, and tumor lysis syndrome, a complication caused by the breakdown of cancer cells.

“We knew [the therapy] could be very potent,” said Dr. David Porter, director of the blood and marrow transplantation program at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia and a coauthor of both papers, which were published in the New England Journal of Medicine and Science Translational Medicine. “But I don’t think we expected it to be this dramatic on this go-around.”

Bone marrow transplants from healthy donors have been effective in fighting some cancers, including chronic lymphocytic leukemia, but the treatment can cause side effects such as infections, liver and lung damage, even death. One-fifth of bone marrow transplant recipients may die of complications unrelated to their cancer, Porter said.

And so researchers have been working for many years to develop cancer treatments that leverage a patient’s immune system to kill tumors with much greater precision. “It is kind of a holy grail,” said Dr. Gary Schiller, a researcher with UCLA‘s Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center who was not involved in the trial.

Earlier efforts to replace risky bone marrow transplants with such engineered T cells proved disappointing because the cells were unable to multiply or survive in patients, Porter said. This time, he said, the T cells were more robust because the team added extra instructions to their virus to help the T cells multiply, survive and attack more aggressively.

About 15,000 patients are diagnosed with chronic lymphocytic leukemia every year, Porter said. Many can live with the disease for years. Bone marrow transplants are the only treatment that eradicates the cancer.

Porter cautioned that these were preliminary results. The scientists plan to continue the trial, treating more patients and following them over longer periods. The researchers also would like to expand the work to other tumor types and diseases, Porter said.

The hope, scientists said, is that the method would work for cancers that can kill more ruthlessly and rapidly.

“It would be great if this could be applied to acute leukemia, where there is a terrible unmet medical need,” UCLA’s Schiller said.