In the absence of a common narrative shared by the U.S. and China, the two nations are likely to drift more rapidly apart. Trust builds on itself just as distrust builds on itself as well, compounding into deep enmity over time.

BEIJING — I have watched carefully the evolution of China’s concept of a “New Type of Great Power Relationship.” This has been a core element of President Xi Jinping’s foreign policy towards the United States. I am a strong supporter of this concept.

I am well aware of President Xi Jinping’s description of the key aspects of what he means by a “New Type of Great Power Relationship”:

— No Conflict

— No Confrontation

— Mutual Respect

— A “Win-Win” Approach To Mutual Cooperation

My reason for supporting this concept is simple: in 21st century Asia, we should not repeat the mistakes of 20th century Europe. Here in Asia, we can choose a peaceful future, rather than repeating the wars that have blighted so much of Europe’s past. In other words, we should learn from history, not simply repeat it.

Specifically, we can avoid repeating the so-called “Thucydides Trap.” According to the Thucydides Trap, the most dangerous period in international history is when we have a rising power challenging the pre-existing status of establishing powers.

In history, we have seen this with Athens and Sparta; and more recently with Britain and Germany, and Germany and Russia. In fact, according to Graham Allison, the director of the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government, history tells us that in 11 of 15 cases over the last 500 years, when an emerging great power challenged an established great power, the result was war.

History, therefore, teaches us that preserving the peace in Asia in the future will not be easy. But with strong political leadership and with a common strategic vision for our region’s future, we can, I believe, preserve the peace.

And I believe, preserve the peace in a manner which sufficiently, but imperfectly, embraces the values and interests of all. The alternative is simply drifting inevitably towards conflict and war. And I sometimes fear that too many people in our region have either forgotten, or have no experience of, how destructive and devastating war really is.

‘Art Of War’ In The Warring States Period

When we analyze Sun Tzu’s “Art of War,” it is important to understand the historical and philosophical context in which it was written. Scholars disagree when the “Art of War” was exactly written. Some argue that it was actually written by the historical figure Sun Wu in the early 5th century BC. Others argue that it was compiled in the 4th or 3rd centuries BC. Students of China would understand how complex a period this was in Chinese history. Following the Xia, Shang and Western Zhou dynasties, China entered a period of long-term political fragmentation.

During the so-called Spring and Autumn period (771 BC to 476 BC), there was a proliferation of independent states that increasingly severed their feudal links with the Zhou dynasty. By the time we reach the beginning of the 5th century BC, China enters what is called the Warring States period (475 BC to 221 BC). It was during this 250-year period that the hundreds of contending states were gradually reduced to just seven major states: Qi, Chu, Yan, Han, Zhao, Wei and Qin. Of course, we all know the final result: China was successfully militarily united under the Qin in 221 BC.

Therefore, when we are locating Sun Tzu’s “Art of War” within this historical framework, it needs to be seen as a guide to the complex tasks of political and military struggle, survival and in some cases, triumph at a time when war was a permanent condition. As Sun Tzu says in the opening line of “Art of War”: “The art of war is of vital importance to the State. It is a matter of life and death, a road either to safety or to ruin. Hence it is a subject of inquiry that can on no account be neglected.”

Strategy Is Not Philosophy

Nonetheless, Sun Tzu’s “Art of War” was not intended as a comprehensive political philosophy of the state, nor was it intended as a text of moral philosophy.

In the periods of Chunqiu and Zhanguo, which lasted half a millennium, there were hundreds of contending philosophical schools. It was during these 500 years that China’s major philosophical schools emerged, including Confucianism, Daoism, Mohism and Legalism.

Confucianism emphasized the hierarchical nature of the society and the state. This hierarchical order was regulated by cardinal principles including “Yi”, “Xiao”, “Li” and “Ren” — respectively, “righteousness”, “filial piety”, “rituals and ceremony”, and “benevolence.”

Daoism, by contrast, did not strive to construct a philosophy for society and the state, but rather a philosophy for the individual and his or her relationship with the cosmos. Daoism emphasizes the three core moral principles of compassion, moderation and humility.

For this reason, throughout Chinese history many scholar officials publicly professed Confucianism as their official orthodoxy but privately practiced Taoism (and later Buddhism) as the preferred path to inner peace.

By contrast, Mo Zi advocated a doctrine of universal love and of non-violence. It represented a radical departure from the mainstream tradition. Given the time, this school did not prosper.

Finally, there is so-called legalist school, expressed through the works of Li Si, Han Fei Zi and Guan Zi. Chinese legalism is often interpreted as an Eastern version of Machiavellianism. Whereas Confucianism and Daoism emphasize moral virtue as a precondition for the proper governance of the state, legalism, by contrast, argues that the well-being of the state would be best guaranteed by clear-cut rules rather than any reliance on private morality.

“Legalism argues that the well-being of the state would be best guaranteed by clear-cut rules rather than any reliance on private morality.”

Legalism ultimately triumphed with the success of the Qin State in 221 BC and the unification of China under Qin Shi Huang. Based on this analysis, Sun Tzu’s “Art of War” (literally translated as Sun Tzu’s Military Methods) has more in common with legalism than any of the other philosophical schools. But it would be incorrect to argue that the other philosophical schools, particularly Confucianism, did not engage in the strategic and conceptual questions of the professional management of military affairs.

Nonetheless, my overall point is that within the framework of ancient Chinese philosophy, Sun Tzu’s “Art of War” was primarily seen as a military handbook for use by Chinese rulers and commanders. It was not seen as a substitute for the values that were central to the more comprehensive philosophical and political systems such as Confucianism.

The reason I emphasize this distinction is that more than 2,000 years later, it is also equally important to separate out the wider debates about global values, institutions and policies on the one hand from the practical consideration of political and military strategies and tactics on the other.

Of course, in all of our countries, both these traditions are important: political philosophies on the broader role of the state in society; as well as narrower debates about the specific military strategy to be adopted by the state for its own security.

The Seven Military Classics

While the Sun Tzu’s “Art of War” is the most famous text on military strategy, both within China and across the world, the truth is it is one of a number of “military classics” written over several centuries. They are generally referred to as the “Seven Military Classics” of Ancient China:

— Tai Gong’s Six Secret Teachings

— The Methods of the Sima

— Sun Tzu’s Art of War

— Wu Zi

— Wei Liao Zi

— Three Strategies of Huang Shi Gong

— Questions And Replies Between Tang Tai Zong And Li Wei Gong

[Note: All quotations that follow are taken from”The Seven Military Classics of Ancient China” translated and edited by Ralph D. Sawyer, Westview Press, 1993]

The reason I emphasize this broader literature is that within China they are all drawn upon, not just Sun Tzu’s “Art of War.” For example, President Xi Jinping has often drawn on the “Methods of Sima” (roughly a contemporary of Sun Tzu’s “Art of War”). In a number of his public addresses Xi has drawn repeatedly on the following phrase from the “Methods of the Sima”: “Thus even though a state may be vast, those who love warfare will inevitably perish.”

“Even though a state may be vast, those who love warfare will inevitably perish.”

Here the Chinese president is emphasizing China’s peaceful rise. But as someone who has read Chinese history extensively, Xi would also be aware of the following phrase in the “Methods of the Sima” which warns: “Even though calm may prevail under Heaven, those who forget warfare will certainly be endangered.”

This, of course, goes to the military preparation in which all countries engage to safeguard their national security. In this respect, the “Methods of the Sima” is a text which balances a strong preference for peace, good government and sound administration with a parallel recognition that military preparedness is equally necessary.

This is clearly reflected in the opening sentence of the “Methods of the Sima”: “In antiquity, taking benevolence as the foundation and employing righteousness to govern constituted uprightness. However, when uprightness failed to attain the desired [moral and political] objectives, [they resorted to] authority. Authority comes from warfare, not from harmony among men.”

Furthermore, the “Methods of the Sima” makes clear the distinction between the civilian and military functions of the state:

In antiquity the form and spirit governing civilian affairs would not be found in the military realm; those appropriate to the military realm would not be found in the civilian sphere. If the form and spirit [appropriate to the] military realm enter the civilian sphere, the virtue of the people will decline. When the form and spirit [appropriate to the] civilian sphere enter the military realm, then the virtue of the people will weaken.

This distinction is important to bear in mind when we analyze the specific teachings of Sun Tzu’s “Art of War.” Consistent with our analysis of the “Methods of the Sima,” and its clear distinction between civilian and military affairs, we must recognize that Sun Tzu did not set out to define a philosophy for the individual, for society or even for the state itself.

How To Fight War If It Can’t Be Avoided

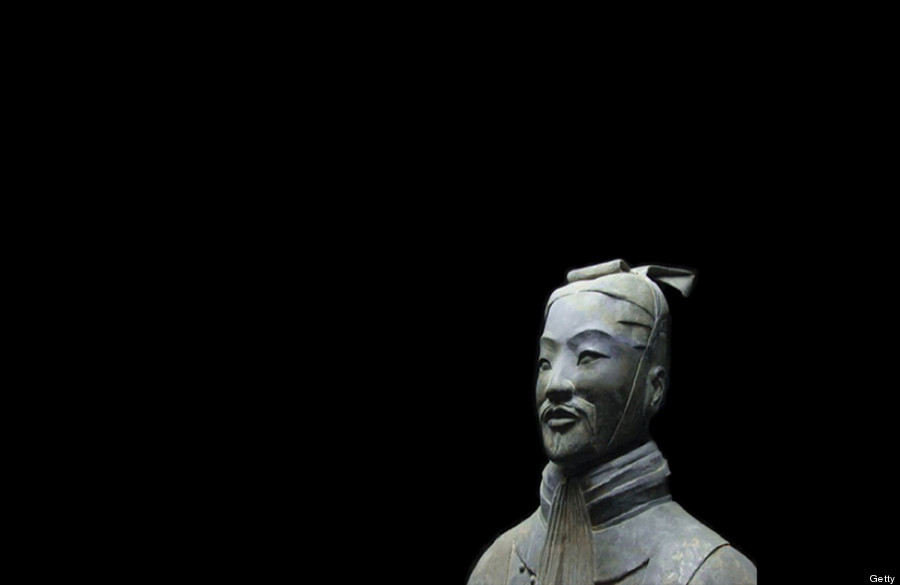

terracotta warriors

What the “Art of War” does provide is a handbook on how war should be fought — if war cannot be avoided.

First, it emphasizes that: “To fight and conquer in all your battles is not supreme excellence; supreme excellence consists of breaking the enemy’s resistance without fighting”; and further that, “The skillful leader subdues the enemy’s troops without any fighting; he captures their cities without laying siege to them; he overthrows their kingdom without lengthy operations in the field” [Chapter 3: 2 and Chapter 3: 6].

Second, Sun Tzu points to the importance of having a clear strategy for prevailing in war, which is made clear in his first chapter “Laying Plans.”

Third, Sun Tzu emphasizes the proper organization of your own forces, including how best to concentrate force [Chapter 5:21].

Fourth, Sun Tzu emphasizes the importance of knowing your enemy. As he says in Chapter 3:18: “If you know your enemy and know yourself, then in one hundred battles you will never be in peril. If you know yourself but not the enemy, for every victory gained you will also suffer a defeat. If you know neither the enemy nor yourself, you will succumb in every battle.”

Fifth, Sun Tzu also underlines the importance of only engaging the enemy at a time, in terms, and on a terrain which is advantageous to yourself. As he said in Chapter 7:15: “In wars, practice dissimulation and you will succeed. Move only if there is a real advantage to be gained.”

Sixth, the “Art of War” warns against entering into alliances. As it says in Chapter 7:12: “We cannot enter an alliance until we are acquainted with the designs of our neighbors.” But Sun Tzu also encourages leaders and military commanders to undermine the alliance of others: “Those who were called skillful leaders of old knew how to drive a wedge between the enemy’s front and rear; to prevent cooperation between his large and small divisions; to hinder the good troops from rescuing the bad, the officers from rallying their men” [Chapter 11:15].

Seventh, in the effective implementation of military strategy, the majority of Sun Tzu’s work emphasizes the importance of espionage, secrecy and deception.

Of course, there may have been a time in history when knowledge of these principles for defeating an enemy was uniquely in the possession of a small number of Chinese rulers. Now, of course, these principles are known almost universally, either through the translation and dissemination of the “Art of War” across China and across the world, or through the collective conclusions of other western military strategists, from Machiavelli to von Clausewitz.

My central point is that the universalization of technical and strategic military knowledge no longer presents any particular party to a military conflict with a particular advantage. Of course, one side may be better or worse in the execution of tactics and strategy over the other. But that is primarily a question of training, rather than the exclusive possession of secret stratagems.

Finally, it should also be emphasized that even within a narrow military context of the time, the “Art of War” dealt with land-based conflict, rather than maritime conflict.

As military strategists are aware, these represent vastly different operating environments and military disciplines. This again is an important distinction from Sun Tzu’s time to the vast array of international security challenges in East Asia today, which are in the main maritime in nature, or involve a combination of naval and air operations. This represents a different strategic context to that of complex, continental, land-based warfare around fundamental questions of state survival.

Therefore, given that Sun Tzu’s “Art of War” was specially designed as a military handbook for the effective conduct of physical warfare, we are left with the fundamental question of what is the broader relevance of the “Art of War” to the challenges and opportunities we face in the regional and global order today?

For me, the most sobering content in all of Sun Tzu’s writings is contained near the end of his work. In Chapter 12:21 and 22, the “Art of War” recalls: “But a Kingdom that has been once destroyed can never come again into being; nor can the dead ever be brought back to life …Hence the enlightened ruler is heedful, and the good general full of caution. This is the way to keep a country in peace and an army intact.”

These sentences from Sun Tzu require us all to pause for deep reflection. We should remember, for example, the impact of the First World War on the previously great powers of Europe.

The bulk of Sun Tzu’s work is how to prevail in a conflict against another state or states by either non-military or military means. Taken in insolation, it can be interpreted as meaning that conflict and war represent the natural and inevitable condition of humankind.

However, the “Art of War” also warns us explicitly, in the section I have just quoted, of the consequences of what happens if you are engaged in conflict or war and you lose. Again this is why Sun Tzu warns us in Chapter 1: 1: “These questions are of vital importance to the State. It is a matter of life and death, a road either to security or to ruin.”

Therefore, the practical question which Sun Tzu presents to us today is how do we preserve the peace so that the implementation of the “Art of War” is in fact rendered redundant?

Or as the “Methods of the Sima” has reminded us, what are the values and virtues of civilian government that need to be deployed in addition to military preparedness? Here I refer to the essential elements of political leadership and effective diplomacy in constructing an alternative reality for the future, rather than implicitly assuming that conflict and war represent the inevitable and unavoidable condition of humankind.

here is nothing determinist about history. Nations choose their futures. And they choose whether they have war or peace. Of course for some these may be easier choices than for others, depending on their geo-political, geo-economic, and geo-strategic circumstances. These choices are shaped too by complex national circumstances including domestic politics, economics, social conditions, cultural factors as well as our very different national historiographies. They are also shaped by our perceptions of each other, whether those perceptions happen to be accurate or inaccurate. But ultimately, taking all these factors into account, our nations choose their futures.

Therefore the core question for the 21st century, this century of the Asia-Pacific, is what future the United States and China choose for themselves, for the region and for the world.

President Xi Jinping has proposed that the U.S. and China develop a “New Type of Great Power Relationship.” His explicit reason for doing so is important: he has said he wants to avoid repeating the mistakes of history, in particular the Thucydides Trap, whereby emerging great powers have almost inevitably ended up fighting wars against the established great power.

Equally importantly, at the Sunnylands Summit in June 2014 President Obama agreed with President Xi that the two sides should develop this concept further.

“How to conceptualize such a relationship in language which is meaningful in both languages is a critical task in itself.”

How to conceptualize such a relationship in language which is meaningful in both languages is a critical task in itself. How then to operationalize it in a way that results in new strategic behaviors towards each other is even more of a challenge.

Conceptual Agreement, Not Rhetoric

Forming a new conceptual framework for the relationship which is meaningful, rather than simply rhetorical, is important. It is important in both countries. America is a country much given to foreign policy doctrines, just as its foreign policy elites focus on how to explain “China policy” to its domestic constituencies and to its allies. And China for itself, given the sheer size of its political apparatus, also requires any new policy direction to be synthesized and simplified into manageable formulations for its 86 million party members.

Previous conceptualizations of the relationship, both American and Chinese, over the last 40 years have ranged across what I have previously called the “seven C’s”:

1. Co-existence

2. Cooperation

3. Contribution (especially in the context of the U.S. concept of China as a responsible global stakeholder)

4. Competition

5. Containment

6. Confrontation

7. Conflict

These generally fall across a spectrum from positive to negative and have been used at different times to characterize different states of the relationship. The important point is practically all these terms have been used by one side characterizing the behaviors of the other, rather than as part of a commonly shared narrative about the relationship’s future.

The evolution of American conceptualizations of the China relationship has been complex. Chinese conceptualizations of the U.S. relationship have also evolved over time. But my core points remain — very few of these conceptualizations of the bilateral relationship have been conjoint.

The basic reality is that as China’s economy grows and supplants the U.S. as the largest economy in the world, and as China gradually begins to narrow the military gap between the two over the decades ahead, there is a new imperative for a common strategic narrative for both Washington and Beijing.

In the absence of such a common narrative (if in fact such narrative can be crafted), the truth is that the two nations are more likely to drift further apart, or at least drift more rapidly apart than might otherwise be the case.

By contrast, a common strategic narrative between the two could act as an organizing principle that reduces strategic drift, and encourages other more cooperative behaviors over time.

So long, of course, as such a narrative embraces the complex reality of the relationship, and avoids motherhood statements which provide negligible operational guidance for those who have day-to-day responsibility, for the practical management of the relationship.

Therefore I argue the relationship needs to consider a new strategic concept for the future that is capable of sufficiently embracing both American and Chinese realities, as well as areas of potential common endeavor for the future, and to do so in language which is comprehensible and meaningful in both capitals.

The Pillars Of A Common Narrative

It should, for example, embrace the following:

First, where the U.S. and China in fact have common values and common interests (even though they may not be entirely conscious of these commonalities), as well as clearly recognizing when certain values and interests are not in common.

Second, what the United States and China may be able to actually “construct” together over time in their bilateral relationship, in the region as well in building new global public goods together over time;

Third, how it might be possible for the U.S. and China not only to cooperate in these areas, but also as a result of successful cooperation gradually build greater strategic trust, step by step, between them over time;

Fourth, how to deploy this gradual accumulation of trust over time to better manage, and perhaps reduce, some of the more intractable areas of strategic distrust that realists legitimately point to as ultimately constraining the full normalization of the relationship;

And finally, how to gradually transform the relationship over time.

The Core Concepts

The core concepts here are being “realistic” about strategic commonalities and differences; being “constructive” about areas of strategic cooperation; and being cautiously open to the possibility of using constructive engagement to build strategic trust that in turn may begin to “transform” the relationship over time.

“The easiest thing to do in international relations is to list all the problems. The hardest thing to do is to recommend how problems might be solved.”

The three key terms are therefore realism, constructivism, and, perhaps in time, some possibility of transformation. Or perhaps best summarized as “constructive realism,” given that my realist friends will always doubt the possibility of any fundamental transformation of such a deeply competitive relationship.

The alternative approach is simply to allow strategic mistrust between the U.S. and China to continue to escalate, with the growing possibility of crisis or even conflict.

The easiest thing to do in international relations is to list all the problems. The hardest thing to do is to recommend how problems might be solved.

onceptualizing the future of the U.S.-China relationship is one thing. Operationalizing such a relationship is something else again. There are a number of areas where the U.S. and China can cooperate together, based on common interests and common values.

Below I list just five possible candidates.

Globally, the climate change issue tops the list. Some may regard this as a soft security issue. In many parts of the world, it is already a hard security issue. When rains do not come, when extreme weather events become more frequent and intense, when farmers cannot plant or harvest their crops, these rapidly become hard security questions.

As the world’s largest and second largest carbon emitters, China and the U.S. have an opportunity together to save their own environments and to save the planet. Perhaps neither state can sign a legally binding global treaty. But they can take parallel action and use other mechanisms such as the G20 to bring about a plurilateral agreement. After all, the G20 represents about 90 percent of total global carbon emissions.

The Xi-Obama agreement on climate change in November at the APEC Summit is a highly encouraging, hopeful and potentially historic step along these lines. *(Editor’s note: This sentence was inserted after the APEC Summit since the speech from which this article is adapted was given earlier).

Regionally, the U.S. and China could work together on the question of the denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula. I also know how hard this is. I have spent time in both Seoul and Pyongyang. I also know that neither the U.S. nor Japan will tolerate a nuclear-armed North Korea. I believe if the North Korean nuclear threat can be permanently solved, and inter-Korean relations put on a stable and sustainable footing, the U.S. has no permanent interest in retaining military forces on the peninsula.

Bilaterally, the U.S. and China need to conclude their investment treaty. On this, the U.S. needs to accelerate progress through its own domestic processes.

I believe that a new wave of foreign direct investment in each other’s economies will help bring the countries closer together over time. It’s also good for business. The poor state of much of American public infrastructure provides a big potential market for Chinese investment. Better infrastructure would also make the American public happier. The more the two economies are enmeshed over time, the less likely it is they will end up in conflict or war.

Multilaterally, the U.S. and China could also work on improving the overall effectiveness of the U.N. system. Many people only focus on the disagreements between China and the U.S. at the U.N. Security Council. In fact, there is much they cooperate on in the Security Council as well. Particularly in Africa and in other regions where China has been a constructive partner and contributed much to U.N. peacekeeping. They could also work together more effectively through U.N. specialized agencies on the development, sustainability and humanitarian agendas where China is also now playing a more active role. I believe it is in the deep interests of both countries to have a resilient, effective and respected U.N. system for the future.

Finally, within our own fraught region, we should better attend to the tasks of regional institution building. Unlike in Europe, we do not have a single pan-regional institution capable of enhancing common security and economic cooperation across the region with the objective of reducing historical tensions and enhancing regional unity over time.

“Unlike in Europe, we in Asia do not have a single pan-regional institution capable of enhancing common security and economic cooperation.”

The U.S., China, Russia and other regional powers could take the lead in transforming the existing East Asia Summit into what I have called an Asia Pacific Community over time.

As a region, we need to start cultivating the habits of regional cooperation. One practical area is in region-wide counter disaster management. Work has already begun on this. But it needs to be expanded, particularly when we don’t know when our region’s next big natural disaster will hit. This type of regional security cooperation, under the aegis of an emerging regional institution like an Asia Pacific Community, helps build mutual confidence and trust over time.

Apart from these five areas listed above, there are many other potential areas for a common work program between the U.S. and China as well.

“The emerging practice by Chinese naval Captains of ‘hail and respond’ with their American counterparts has been welcomed by the U.S. military.”

Common rules of the road on cyber security is one such area. Deepening cooperation on global and regional counter-terrorism is another. Common investment in major infrastructure projects in emerging markets in order to share risk, is yet a third.

Similarly, common protocols for managing conflicting security interests should also be embraced. This should involve military to military arrangements to avoid or manage incidents in the air and incidents at sea. For example, the emerging practice by Chinese naval captains of “hail and respond” with their American counterparts has been welcomed by the U.S. military. In other words, there is a long list of projects that could be embraced — some of which are manageable, others apparently intractable.

Constructive Realism

If China and the U.S. are to build a “New Type of Great Power Relationship,” I believe it should be based on a principle of what I have called “constructive realism.” It may be that the best the countries can do is to manage their “realist” differences. And balance this through cooperation in other areas by “constructing” a new range of global, regional and bilateral “public goods” for the future.

But as I indicated above, it might also be possible to aim a little higher for the longer term future as well. I am not an idealist. I am a constructive realist. But if both sides can reach agreement on a range of new areas, it might just be possible to use these successes to change the overall content and atmosphere of the relationship over time as well.

Trust tends to build on itself. Just as distrust builds on itself as well, compounding into deep enmity over time.

“Trust tends to build on itself. Just as distrust builds on itself as well, compounding into deep enmity over time.”

There is a further reason to consider the possibilities of transforming the relationship in the long term. And that is it is impossible to predict the power relativities between the two countries out to mid-century.

Things could go wrong for either country. Many Chinese friends have concluded that the U.S. is in inexorable decline. They may be right. I’m not so certain.

The Americans have a remarkable capacity to reinvent themselves. They are a growing population. And if we think, as many Americans now do, of an integrated North America in the future, including the integrated product and increasing labor markets of Canada, the U.S. and Mexico, by mid-century, we are looking at an integrated economy of 5-600 million people.

This may not be insignificant, particularly after China’s population peaks by 2030, and starts to decline. Whatever the future may hold for both countries in terms of their relative size, capabilities and influence, it makes sense for these two great civilizations to work towards a common view of the planet, the world and our wider region here in Asia.

Nations Choose Their Future

Nations get to choose their futures. And I remain optimistic that the U.S. and China can still choose a positive future for themselves and the world. That is why both sides need to explore how best to give definition to the concept of a new type of strategic relationship between them.

To define this conceptually is important because strategic concepts and the language around them are important organizing principles in both countries, but particularly in a country as vast as China. And as I have noted above, both the concepts and the language have to work equally effectively in both English and Chinese.

The time has well and truly passed when the language of international relations should be exclusively written in English. And it is easier than we think for complex concepts to be simply lost in translation.

“The time has well and truly passed when the language of international relations should be exclusively written in English.”

That’s in part why I emphasize words like “realistic”, “constructive” and “reform.” These are positive words in Chinese. They are also positive words in English. Xianshi, Jianshe, Gaige, or when put together: U.S.-China Relations: Realistic, Constructive, and, over time, Transformative.

Of course all of this takes time. Rome was not built in a day. That is why we need to also reflect on some modern Chinese political wisdom to help us as well. What we are describing is a gradual process but with a clear view of a destination: namely a “New Type of Great Power Relationship.”

Deng Xiaoping described a similar, gradual process of reform domestically over 30 years ago. Deng roughly said that we must cross the river, feeling the stones, one by one. His strategic destination was a modern China. But he recognized the process for getting there was feeling your way, one step at a time.

And that strategy has succeeded in producing the modern China we have today. I believe this wisdom also applies to China’s role in the world, as well as its relationship with the United States. Perhaps the overall logic is something like this: Based on realist foundations; but nonetheless beginning to construct new bilateral, regional and global public goods together; so that step by step the relationship is transformed by building strategic trust over time.

The Salutary Warnings Of ‘The Art Of War’

As a last point, let’s return once again to the wisdom of Sun Tzu’s “Art of War.” Sun Tzu says:

“The art of war is of vital importance to the state. It is a matter of life and death, a road either to safety or to ruin. Hence it is a subject of inquiry that can on no account be neglected.”

????????????????????????

To put it into its current international context, perhaps it would better go like this:

“The art of war is of vital importance to the world. It is a matter of life and death, a road either to safety or to ruin. Hence it is a subject of inquiry that can on no account be neglected.”

????????????????????????????????????????????