I DID WARN HIM : Check His Passions

Prostitutes as a Business Incentive Makes More Sense

These were the words supposedly uttered by France’s president, Nicolas Sarkozy, when he heard that Dominique Strauss-Kahn had been arrested in New York on charges of attempting to rape a hotel maid. When “DSK” moved to Washington, DC, in 2007 to take up his duties as the boss of the IMF, Mr Sarkozy is said to have told him to check his passions: he was going to a country that had come close to hounding Bill Clinton out of office for having an affair with a White House intern.

In matters of sex, as of war, Europeans are from Venus. They mock Americans’ puritanism about the sex lives of public figures. For a politician to cheat on his wife in America is a sign of dishonesty. Witness the opprobrium heaped on Arnold Schwarzenegger over the new revelation that he had fathered a child out of wedlock. In much of Europe, affairs can be a badge of virility. That is the insinuation of an interview given by none other than Mr Strauss-Kahn’s wife, Anne Sinclair. Asked in 2006 whether she minded her husband’s reputation, she replied: “No, I’m rather proud of it! It’s important for a politician to seduce. As long as he seduces me and I seduce him, that’s enough for me.”

Nowhere is the politician’s entitlement to sex more tolerated than, perhaps, in Italy. For Silvio Berlusconi, the country’s longest-serving prime minister in modern times, sexual appetite is a matter of pride, not of shame. He is on trial, charged with paying for sex with an underage prostitute. (He also faces a range of corruption charges.) But there are no handcuffs for Il Cavaliere. “I love life and I love women,” he declares cheerily.

Americans (and, it is true, many Europeans) are mystified by Mr Berlusconi’s ability to survive the tales of his lurid “bunga-bunga” parties. Europeans are bemused by the uptightness of American public life, in which a blow job in the White House can lead to the impeachment of a president. But the case of Mr Strauss-Kahn is about more than sex. Dig deeper and you uncover a number of telling differences in transatlantic attitudes.

One question is: how much privacy should public figures enjoy? American intrusiveness may seem distasteful to Europeans. For their part, Americans do not understand how prominent personalities in Britain can obtain “super-injunctions” preventing journalists from reporting some peccadillo or even the existence of the injunction.

European tolerance of cavorting politicians carries the risk of creating a culture of silence and immunity that too easily blurs the lines between a consensual affair, harassment and outright assault. Henry Kissinger may have thought that power is the ultimate aphrodisiac. But power can also be a means of extorting sexual and other favours. If state and media conspire to keep quiet about the debauchery of politicians, might it not be easier to hide other misdeeds, such as corruption?

When Mr Strauss-Kahn was up for the IMF job, Jean Quatremer, a correspondent for Libération, a French newspaper, was one of the few voices expressing concern about his libertine ways. His attitude towards women, blogged Mr Quatremer, was “too insistent, often brushing close to harassment. A trait known to the media, but about which nobody speaks (we are in France).” Mr Quatremer warned that the IMF was infused with “Anglo-Saxon mores” and that France could not afford a scandal.

With hindsight it looked complacently eager to avoid one. In 2007 Tristane Banon, a young writer, gave a televised account of what she claimed was an attack on her by Mr Strauss-Kahn when she interviewed him for a book in 2002. The programme attracted no attention when first screened, in part because it appeared on an obscure cable channel. But it now makes for compelling viewing. DSK’s name was bleeped out as Ms Banon described him to a table of dining companions as “a rutting chimpanzee” and recounted fighting him off on the floor. Later, she said, DSK would send her creepy texts asking: “Do I frighten you?” She thought about pressing charges but did not want to be known “until the end of my days as the girl who had had a problem with a politician”. Ms Banon’s account would not make her the first female journalist to be harassed by a powerful man. But what is intriguing about this tale is that Mr Strauss-Kahn’s name did not leak, as it surely would have done in America or Britain.

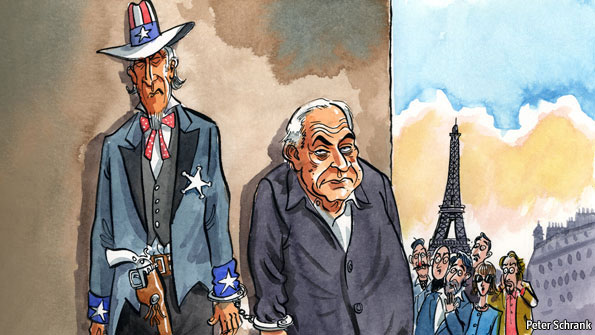

Perhaps inevitably, given the fame of Mr Strauss-Kahn and the anonymity of the chambermaid, more attention has been paid to the tribulations of the former IMF chief than to the plight of his alleged victim. Indeed, the images of Mr Strauss-Kahn in handcuffs during his “perp walk” are regarded by many in France as an assault on the defendant’s dignity, part of a flawed system of justice that places too much emphasis on retribution at the expense of the rights of the accused.

In France parading suspects in public is banned. In Britain, once a defendant is charged, until a trial is concluded only court proceedings may be reported. The aim is to avoid prejudicing jurors. Justice in these countries tends to be a sober affair, insulated as far as possible from external tumult. In America it is more theatrical, with lawyers fighting their case over the airwaves and cameras filming battles in the courtroom. To Americans this is all evidence of great openness.

Beyond such differences in legal cultures, one fact is inescapable. In America a modest African immigrant has obtained a swift response from the police to her complaint of sexual assault. Mr Strauss-Kahn’s innocence or guilt will be determined in court. But New York’s authorities have not shirked from arresting the head of one of the world’s leading international bodies, nor from demanding that he be kept in jail on remand. It is worth asking: would this have happened in Paris or Rome?