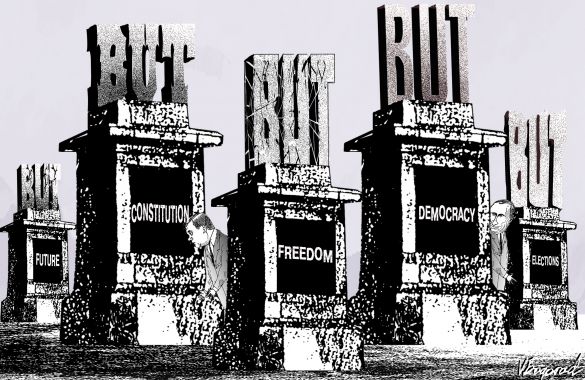

Prime Minister Vladimir Putin has said on several occasions that without normal democratic development, there is no future for Russia. We Russians are pleased to hear these enlightened words, yet Putin invariably adds a “but” to these soaring statements, which weakens them considerably. In fact, Putin’s “but” renders his points senseless.

We have hated the coordinating conjunction “but” ever since the dawn of the Soviet era. Then we were told that freedom is good, but that we can’t live in an individualist society without common concern for the Communist state. Democracy is great, we were told, but only in the interests of the working class.

Now Putin tells us that democracy is indeed great, but that public protests cannot take place in public places, say, around hospitals and the like.

President Dmitry Medvedev does understand — with no “buts” — that “freedom is better than no freedom,” that “legal nihilism” is bad and democracy is good. He understands that Stalin was a criminal, that his order to murder Polish officers in Katyn was an act of depravity that has no excuse or explanation. Unfortunately, we don’t understand the role Medvedev politics plays in Russia. He says all the right things, yet they don’t seem to be reflected in reality.

The Dissenters’ Marches, which take place on the 31st of every month to mark Article 31 of the Constitution guaranteeing freedom of assembly, could be — and are — easily dismissed as a marginal protest of a few hundred people with no common goals or ideas. Putin’s and Medvedev’s poll numbers are so high, many argue, that they don’t need to care about a few dissenters. Besides, most Russians support the government with no dissent at all, they say. This doesn’t say much, however, because the Russian majority always supports the government, regardless of the policies it implements.

Today’s dissenters are indeed a minority and of course can be disregarded, but only up to a point. After all, this minority is made up of the country’s best thinkers — musicians, artists, writers, and those who develop science, technology and economic innovation. Such people cannot be dismissed as useless, since we need the innovation that they deliver even if we think Russia doesn’t need democracy. True, not all members of the thinking minority attend the dissenters’ marches, yet many more of them silently oppose the regime.

Russia’s leaders talk obsessively of the country’s industrial modernization, of their support for innovations, such as nanotechnology, that can help the country catch up to the developed world. In line with Soviet traditions, a nanotechnology project was given a chunk of land, financing and assigned a grandiose name: Innovation City. The best brains in Russia will gather in one place and move the country forward. The hope is that Russians at home, and especially abroad, will be overcome with patriotic feelings. Drawn by high salaries, emigres will return to make themselves famous and their motherland proud.

A wonderful plan, but I fear that it won’t work. For example, imagine a genius who left Russia many years ago. He has achieved prominence in a foreign country for inventing something outstanding. Now he is asked to come home: Your motherland is waiting for you, it values your contribution, it forgives your betrayal, and it will pay you more than what you are getting elsewhere.

To give the plan the benefit of the doubt, the brilliant scientist is nostalgic for the birch trees, his old friends, his ex-wife and children from the first marriage. He wants to come back, to revisit all that he has left behind, while also helping his nation become economically strong, technically advanced, and prosperous. Yet before making the final decision, he turns on the radio, watches a bit of television, browses the Internet and finds out what Russia is like. Journalists are killed, scientists are accused of espionage, and former Yukos CEO Mikhail Khodorkovsky remains unjustly imprisoned. He reads the confused and confusing speeches of our leaders: freedom is good, but …

This brilliant scientist learns that Vasily Aleksanyan, the terminally ill former Yukos lawyer, was held in prison in inhuman conditions; that corporate lawyer Sergei Magnitsky died in pretrial detention after being refused medical treatment; and that human rights lawyer Stanislav Markelov was gunned down on a Moscow street. Then this scientist will be surprised to discover that Russians voted Stalin the third most popular “Face of Russia.”

In the meantime, his junior colleague in Russia does not attend the Dissenters’ March, but simply emigrates — perhaps the highest form of protest.

In Soviet times, Communist leaders tried to lure people into the collective farms with promises of great crops and spectacular meat production. Nothing worked because the agricultural system was incompatible with high achievement in the long run.

Similarly, in a country where the concepts of democracy and freedom are balanced by “but,” achievements in science, technology and economy are impossible.

The thinking minority needs an effective system of laws and institutions, genuinely free and fair elections, a working parliament with opposition parties and a judicial system that is independent, rather than subservient to orders from above.