Secretive Geofence Surveillance Software Being Snapped Up By Law Enforcement

Image: Fog Reveal

Image: Fog RevealFog Reveal hoovers up cell phone location data by tracking ad ids and pings from local censors, and then sells it to law enforcement. It doesn’t require a search warrant but can display your pattern of life within minutes. Its use is seldom mentioned in court cases; one spokesman said, “The success lies in the secrecy.”

EFF reports in Inside Fog Data Science, the Secretive Company Selling Mass Surveillance to Local Police:

EFF could not verify Fog’s claims. But there is reason to be skeptical: Thanks to the nature of its data sources, it’s likely that Fog can only access location data from users while they have apps open, or from a subset of users who have granted background location access to certain third-party apps. Public records indicate that some devices average several hundred pings per day in the dataset, while others are seen just a few times a day.

TN Editor

Local law enforcement agencies from suburban Southern California to rural North Carolina have been using an obscure cellphone tracking tool, at times without search warrants, that gives them the power to follow people’s movements months back in time, according to public records and internal emails obtained by The Associated Press.

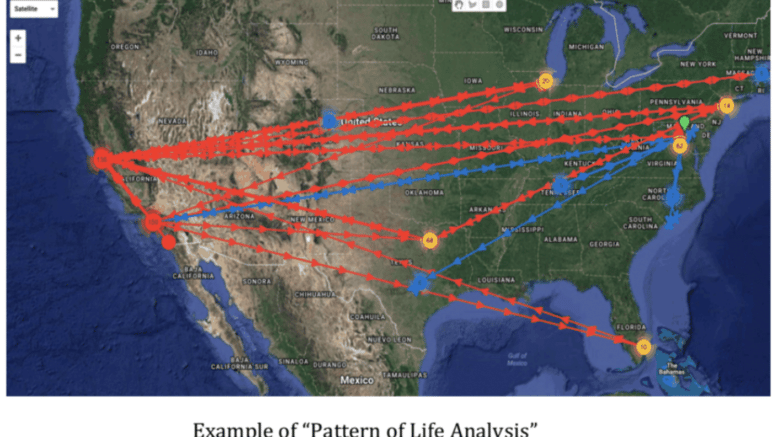

Police have used “Fog Reveal” to search hundreds of billions of records from 250 million mobile devices, and harnessed the data to create location analyses known among law enforcement as “patterns of life,” according to thousands of pages of records about the company.

Sold by Virginia-based Fog Data Science LLC, Fog Reveal has been used since at least 2018 in criminal investigations ranging from the murder of a nurse in Arkansas to tracing the movements of a potential participant in the Jan. 6 insurrection at the Capitol. The tool is rarely, if ever, mentioned in court records, something that defense attorneys say makes it harder for them to properly defend their clients in cases in which the technology was used.

The company was developed by two former high-ranking Department of Homeland Security officials under ex-President George W. Bush. It relies on advertising identification numbers, which Fog officials say are culled from popular cellphone apps such as Waze, Starbucks and hundreds of others that target ads based on a person’s movements and interests, according to police emails. That information is then sold to companies like Fog.

“It’s sort of a mass surveillance program on a budget,” said Bennett Cyphers, a special advisor at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a digital privacy rights advocacy group.

The documents and emails were obtained by EFF through Freedom of Information Act requests. The group shared the files with The AP, which independently found that Fog sold its software in about 40 contracts to nearly two dozen agencies, according to GovSpend, a company that keeps tabs on government spending. The records and AP’s reporting provide the first public account of the extensive use of Fog Reveal by local police, according to analysts and legal experts who scrutinize such technologies.

“Local law enforcement is at the front lines of trafficking and missing persons cases, yet these departments are often behind in technology adoption,” Matthew Broderick, a Fog managing partner, said in an email. “We fill a gap for underfunded and understaffed departments.”

Because of the secrecy surrounding Fog, however, there are scant details about its use and most law enforcement agencies won’t discuss it, raising concerns among privacy advocates that it violates the Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which protects against unreasonable search and seizure.

What distinguishes Fog Reveal from other cellphone location technologies used by police is that it follows the devices through their advertising IDs, unique numbers assigned to each device. These numbers do not contain the name of the phone’s user, but can be traced to homes and workplaces to help police establish pattern-of-life analyses.

“The capability that it had for bringing up just anybody in an area whether they were in public or at home seemed to me to be a very clear violation of the Fourth Amendment,” said Davin Hall, a former crime data analysis supervisor for the Greensboro, North Carolina Police Department. “I just feel angry and betrayed and lied to.”

Hall resigned in late 2020 after months of voicing concerns about the department’s use of Fog to police attorneys and the city council.