THE north-eastern Nigerian town of Chibok is spared little. Earlier this year fighters from the extremist group, Boko Haram, abducted more than 200 local schoolgirls. In the past week insurgents and government troops have traded possession of urban districts and surrounding farmland, leaving much of it burnt.

The Nigerian army, one of the biggest in Africa, should have little difficulty scattering the amateur jihadists. But its arsenal is decrepit and its troops poorly trained. Hence the government’s decision to spend $1 billion on new aircraft and training, among other things. Critics question how much will go towards appropriate kit (never mind how much gets stolen by corrupt generals) and whether it is sensible to lavish resources on a force implicated in atrocities and human-rights abuses.

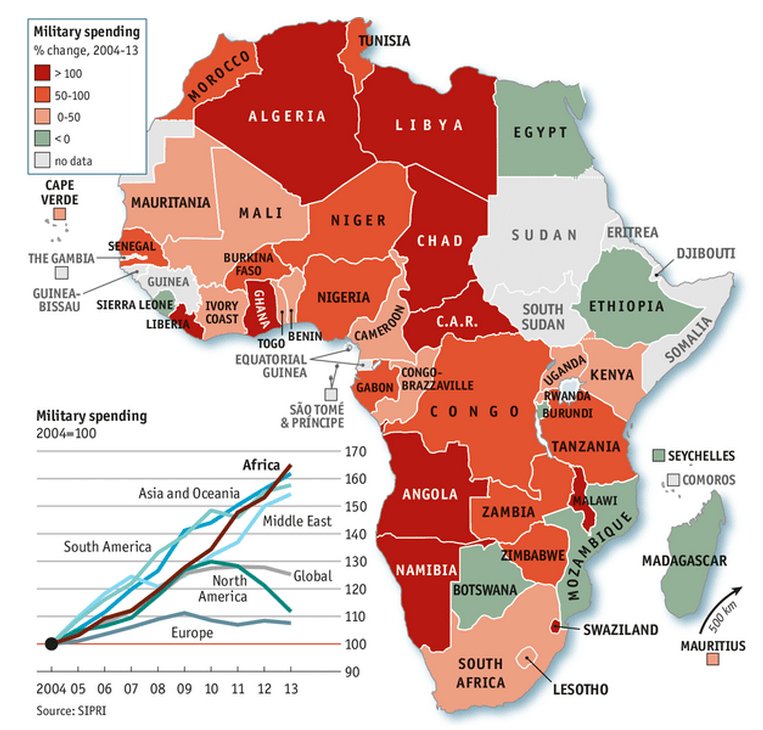

These questions resonate across Africa. Last year military spending there grew by 8.3%, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), faster than in other parts of the world (see chart). Two out of three African countries have substantially increased military spending over the past decade; the continent as a whole raised military expenditure by 65%, after it had stagnated for the previous 15 years.

Angola’s defence budget increased by more than one-third in 2013, to $6 billion, overtaking South Africa as the biggest spender in sub-Saharan Africa. Other countries with rocketing defence budgets include Burkina Faso, Ghana, Namibia, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe. The continent’s biggest spender by far is Algeria, at $10 billion.

“Some countries are buying really amazing stuff,” says David Shinn, a former American diplomat, now a professor at George Washington University. Ethiopia last year took delivery of the first of about 200 Ukrainian T-72 tanks. Neighbouring South Sudan has bought about half as many. Coastal states such as Cameroon, Mozambique, Senegal and Tanzania are sprucing up their navies. Angola has even looked at buying a used aircraft-carrier from Spain or Italy.

Chad and Uganda are buying MiG and Sukhoi fighter jets. Cameroon and Ghana are importing transport planes to boost their ability to move troops around and deploy them abroad, which they have been ill-equipped to do. For peacekeeping duties they generally ask friendly Western governments for help in airlifting troops, or charter civilian planes.

Despite such handicaps, many are participating in a growing number of African Union and UN peacekeeping missions. Once rarely seen in blue helmets, sub-Saharan soldiers are increasingly replacing troops from Europe and Asia. Ethiopians and Rwandans have acquired a reputation as reliable peacekeepers, all the while benefiting from training as well as from reimbursements for purchases of weapons. A new “business model” for African defence ministries is taking shape.

Many African armies are becoming more professional, too. Their troops are more often paid on time, get decent food and go on regular leave, all of which boosts morale and discipline. “Even small countries like Benin and Djibouti now field respectable forces,” says Alex Vines of Chatham House, a think-tank in London.

A big issue is whether troops have enough training to handle sophisticated new gear. Chad makes good use of its Sukhoi SU-25 jets–with the help of mercenaries. On the other hand, Congo-Brazzaville only manages to get its Mirage fighter jets into the air for national-day celebrations. South Africa bought 26 Gripen combat aircraft from Sweden but has mothballed half of them because of budget cuts. Uganda spent hundreds of millions of dollars on Sukhoi SU-30 combat aircraft but little on the precision weapons to go with them.

The reasons for African governments to boost arms spending vary. High commodity prices over the past decade (they are now falling) have filled the coffers of many. Some leaders have been tempted to buy expensive arms to gain prestige. Other are suspected of inflating deals to siphon off money for themselves.

Tanks for everything

But some spending is prompted by genuine security threats. The Sahel and parts of east Africa face a range of extreme jihadists. Coastal states have seen piracy soar, most recently in the west. Offshore discoveries of oil and gas have increased the need for maritime security. More traditional threats, internal as well as external, persist in countries such as South Sudan, where the government is fighting rebels while also facing a hostile northern neighbour.

Industrial ambition also plays a part. A number of countries hope to foster defence manufacturing at home. A huge South African purchase of arms from, among others, Germany and Britain, agreed to more than a decade ago, included promises of “offsets” whereby local firms would help assemble jets and ships. Angola plans to build its own warships. Nigeria and Sudan make ammunition. Four European arms manufacturers set up African subsidiaries this year: Antonov is going into Sudan; Eurocopter is in Kenya’s capital, Nairobi; Fincantieri, an Italian shipbuilder, is in the country’s main port, Mombasa; and Saab is setting up a plant for its military aircraft in Botswana.

These military improvements carry risks. Ambitious officers may misinterpret new might for political right–and may be tempted to seize power, as many have done before. Sophisticated arms may also fall into the wrong hands; witness the array of Libyan weapons that have fuelled conflicts across Africa, from Mali to the Central African Republic, since the fall of Muammar Qaddafi.

These structural changes to African armies may gradually alter the type of war that could be fought on the continent. Since the anti-colonial guerrilla wars of the past century, most African conflicts have been internal. Few countries previously had the ability, let alone the inclination, to fight their neighbours. In the late 1990s, several countries, including Angola and Zimbabwe, sent forces to take part in Congo’s civil war–to little avail. Ethiopia and Eritrea fought each other in 1998-2000. Tanzania sent its army into Uganda, along with guerrillas returning from exile, to overthrow Idi Amin in 1978. In general, however, few disputes between African countries have been liable to spark wars. But the build-up of beefier armies is bound to carry a risk.