William Gibson lives in an overwhelmingly green suburb with old-money roots south of Vancouver’s downtown, and it is in this suburb that I am currently wandering, looking for William Gibson. Yesterday, over lunch, he’d given me an address that seems not to actually exist, and just a minute ago, over the phone, he gave me a real address that wasn’t his. I know this because I’m standing in front of a massive gated house, the kind of house in which a reclusive beverage magnate might live, marveling at the elaborate hedges, when Gibson appears behind me. He’s laughing.

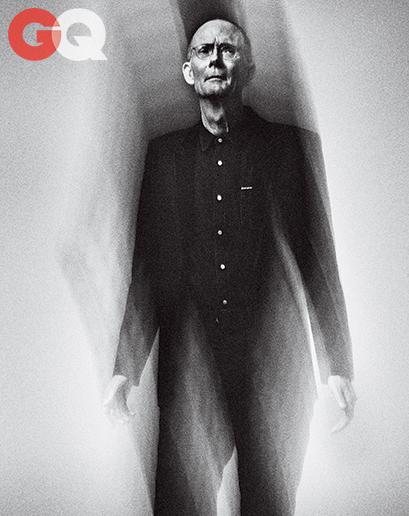

“I’m not that rich,” he says, apologizing for the confusion. He’s wearing wire-framed glasses and has a kind of severe oracular thinness that complements his severe six-foot-four-inch height. At 66 he is permanently bent over, breaking-wave-shaped, the result of a lifetime of leaning down to listen. He points across the street at a more modest but still quite stately home where he actually lives.

Inside it’s Arts and Crafts-y, wood floored, quiet. We sit in the living room, and without ceremony he picks up where we left off the day before.

“I figured out the two things where I was most dumbstruck,” Gibson says. “The two questions were: Was I thinking about retiring? Which I still haven’t got my head around. But the other one, which I think is gonna be the big one when I tour with this book”—The Peripheral, his tenth and most recent novel—”is: Have I been too terribly bleak, or do I think the world is absolutely fucked?”

And do you?

“I don’t have an answer for that yet,” Gibson says, the light slanting through his windows. “In retrospect, I think I wrote the book to try to find out.”

We all should probably hope William Gibson doesn’t think the world is fucked. In the thirty years since the publication of his first novel, Neuromancer, he’s gotten plenty wrong about the future but also an unsettling amount of it right. We have Neuromancer to thank for making ubiquitous the word cyberspace, which Gibson described as “a consensual hallucination”—still maybe the best description of whatever it is we now spend most of our days doing. Since then, in books like Virtual Light (1993) and Idoru (1996), he’s imagined a pretty convincing facsimile of modern reality television, long before the advent of anything that actually resembled modern reality television; a cure for AIDS that increasingly seems like a way we will in fact finally cure AIDS (Virtual Light again); and a whole host of other now familiar ideas about nanotechnology and viral marketing and drones shaped like silvery penguins that swim through the air (2010’s Zero History; yes, they do exist).

His hard-boiled books—cool but not cold, deceptively well written—go by in tangles of sleek sentences. Uncannily prescient ones. “I was never able to predict,” Gibson says. “But I could sort of curate what had already happened.”

The Peripheral is an emphatic return to the science fiction he ceased to write after the turn of this century, set in not one but two futures. The first, not far off from our own present day, takes place in a Winter’s Bone-ish world where the only industries still surviving are lightly evolved versions of Walmart and the meth trade. The second future is set further along in time, after a series of not-quite-cataclysmic events that have killed most of the world’s population, leaving behind a monarchic class of gangsters, performance artists, and publicists in an otherwise deserted London. Like many Gibson books, The Peripheral is basically a noirish murder mystery wearing a cyberpunk leather jacket and, after an uncharacteristically dense first one hundred pages, a super enjoyable read—though perhaps less so when you consider just how accurate Gibson can be when he’s thinking about what might come next.

Because according to The Peripheral, what is coming next is, to borrow Gibson’s phrase again, well…fucked.

···

For a while, characters in William Gibson novels tended to be orphans, or had mothers who left, or were otherwise bereft of family. And though not much in Gibson’s books is directly autobiographical, it’s impossible not to read this tendency against the story of Gibson’s own life, which for a while was uncommonly, improbably sad.

“Well, the whole thing—it’s a story of trauma,” Gibson begins, sitting on his couch. He is not a guy to self-dramatize. He’s goofy, colloquial as a 22-year-old, a father of two. Smiles a ton. “Like, major trauma.”

The story starts in the American South—Tennessee, North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia, states through which Gibson’s family would follow his father’s construction business, until his father died. He’d been away on business and choked to death. This was before people knew to do the Heimlich maneuver, Gibson recalls neutrally. “Just one of those things that could just take anybody out.”

Gibson was 7 or 8, he doesn’t remember exactly. He and his mother moved back to her childhood home of Wytheville, Virginia, a tiny town where the modern world scarcely existed. He read science fiction and fantasized about leaving; finally his mother sent him to boarding school in Arizona.

Then she died, too.

Gibson had just turned 18. “She collapsed on the street one day,” he says.

It was 1966, and Gibson basically lost his mind for a while. He remembers coming to, temporarily jolted out of whatever fog of grief he was in, while riding an overnight bus to Toronto. It was that moment when he first saw the future, the signature dystopian vision now familiar from his books, where the sky is always gray or the color of television tuned to a dead channel.

It looked like trash.

“In the morning, when the light was coming up, I saw green plastic garbage bags for the first time in my life,” Gibson remembers.

“Millions of them, because, as it happened, there was a municipal strike going. And I couldn’t understand why there were so many of them, and I had to infer their purpose. Isn’t that strange?”

···

An enormous orange cat joins the two of us in Gibson’s living room, and in the momentary silence I remind Gibson that I never actually brought up retirement—he did.

“Yeah,” Gibson says after a long pause. “That’s right. But subsequently I think I sort of realized that I’m just not there.”

Which is a relief: Gibson’s writing is so thoroughly part of the world now that it’s hard to imagine a world without it. His work has permeated the culture to the point that even he can’t tell what’s his and what isn’t. Even something as randomly familiar as a bar-code tattoo: That was Gibson’s idea, something he imagined in an early screenplay draft for Alien 3, Gibson’s first—though not last—foray into screenwriting, and the only bit of his that made it into the finished film.

Gibson’s Hollywood years are lesser known than his books, probably for good reason. In the ’90s, a bunch of producers somehow gave Gibson and the artist Robert Longo $26 million to make the film that would become Johnny Mnemonic, a movie that climaxes with Ice-T leading a crossbow battle against the yakuza while Keanu Reeves hacks his own brain with the aid of a heroin-addicted dolphin. Gibson remembers staying at the Chateau Marmont for months—years—as the film descended into development hell, batting away questions from the studio like: Can the dolphin perhaps not be addicted to heroin?

“That’s a thing that really happened,” Gibson says, laughing.

Johnny Mnemonic was released in 1995, to deservedly disastrous reviews, and Gibson returned to his desk, where he filled his next two novels, Idoru and All Tomorrow’s Parties, with acidly satirical meditations on fame and the entertainment industry. Four years later, a movie called The Matrix—another term Gibson popularized in Neuromancer—came out, also starring Keanu Reeves as a guy who hacks his own brain, and grossed $463 million: a Hollywood message of some sort, though by then Gibson wasn’t around to listen.

For nearly two decades, he’d been writing science fiction set somewhere off in the future. But then, at the dawn of this century, the present started seeming weirder than anything he could imagine, so he began writing about that instead. The subsequent three books he published—Pattern Recognition (2003), Spook Country (2007), Zero History (2010)—were thrillers in a different, more mature mold, DeLillo-esque but pop, too: about marketing consultants hunting shadowy filmmakers, or former indie-rock front women investigating stolen shipments of cash. For the first time, Gibson found himself on the New York Times best-seller list.