Karzai’s China-Iran dalliance riles Obama

By M K Bhadrakumar

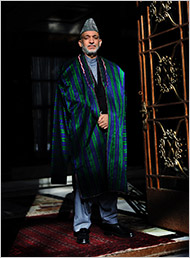

Great moments in diplomatic timing are hard to distinguish when the practitioners are inscrutable entities. Afghan President Hamid Karzai’s visits to China and Iran within the week rang alarm bells in Washington which were heard in the Oval Office of the White House.

Karzai’s two days of talks in Beijing last week were scheduled exactly at the same time as the high-profile strategic dialogue taking place between the United States and Pakistan in Washington.

Karzai has coolly defied the President Barack Obama’s do-or-die diplomatic campaign to “isolate” Iran in the region – not once but twice during the past fortnight. Karzai earlier received his Iranian counterpart, Mahmud Ahmadinejad, with manifest warmth in Kabul while the US Defense Secretary Robert Gates was on a visit to Afghanistan.

Washington lost no time signaling its displeasure. Obama flew into Kabul on Sunday unannounced for an “on the ground update” from Karzai.

US national security advisor James Jones told the White House press party that Obama hoped to help Karzai understand that “in this second term there are things he has to do as the president of his country to battle the things that have not been paid attention to almost since day one”.

Jones’s unusually sharp comment bears out the New York Times report from Kabul that Obama “personally delivered pointed criticism” to the Afghan president that “reflected growing vexation” with him.

The newspaper commented:

Mr Obama’s visit to Afghanistan came against a backdrop of tension between Mr Karzai and the Americans. It quoted a European diplomat in Kabul as saying, “He’s [Karzai] slipping away from the West” and it went on to point out that the Afghan president “warmly received one of America’s most vocal adversaries” in Kabul and then “met with him again this past weekend in Tehran”, apart from visiting China, “a country that is making economic investments in Afghanistan, … taking advantage of the hard-won and expensive security efforts of the US and other Western nations.”

It seems Karzai had barely got back to Kabul from Tehran when the US Air Force One carrying Obama landed in Bagram air base north of the Afghan capital. Obama has since asked Karzai to go over to Washington on May 12.

Spring is in the air Clearly, the Americans are furious that Karzai is steadily disengaging from the US’s grip and seeking friendship with China and Iran. Pretences of cordiality are withering away even as Washington realizes that the ground beneath its feet is shifting.

Curiously, two days after his return to Kabul from Beijing on Thursday, Karzai flew to Tehran to celebrate Nowruz festival. By celebrating the advent of spring at an extraordinary conclave of Persian-speaking regional countries in Tehran, Karzai drew attention to Afghanistan’s multiple identity as a plural society of pre-Islamic antiquity.

But in political terms, he ostentatiously displayed his freedom from American control. His itinerary in Tehran included a meeting with Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

If Karzai’s Iran diplomacy was rich in political symbolism, his state visit to China was politically substantive. Karzai was accompanied by the Afghan ministers of foreign affairs and defense. China’s Xinhua news agency reported from Beijing that Karzai’s upcoming visit “has drawn wide attention at a time when major powers are speculating whether China would engage deeper in efforts to rebuild – and possibly offer military assistance to – the war-torn country.”

Xinhua scotched speculation regarding any role for China in the war:

Since early 2008, Afghan officials, as well as the NATO [North Atlantic Treaty Organization] troops, have repeatedly asked China to open the border on the east end of the Vakhan corridor to help them fight terrorists in the country. China has rejected the appeal, refusing to be sucked into a war on terror. … Foreign Minister Yang Jiechi said earlier this month that military means would not offer a fundamental solution to the Afghan issue.

Zhang Xiaodong, deputy head of the Chinese Association for Middle East Studies, was quoted as saying, “China definitely will not participate in the country’s internal affairs under the NATO framework”.

Zhang challenged the call last month by NATO secretary-general Anders Fogh Rasmussen to reinforce the alliance’s ties with Asian countries such as China, India and Pakistan as well as Russia, which would have a stake in Afghanistan’s stability. Zhang said “unbalanced engagement by these [Asian] stakeholders” could lead only to more problems.

Zhang added: “Afghanistan should cut its reliance on the US. At the moment, Washington is deeply involved, and it makes other neighbors nervous. Karzai now hopes to seek more support from other big countries and find a diplomatic balance.”

However, in a meeting with his Afghan counterpart, Abdul Rahim Wardak, Chinese Defense Minister Liang Guanglie pledged bilateral military cooperation. “Chinese military will continue assistance to the Afghan National Army to improve their capacity for safeguarding national sovereignty, territorial integrity and domestic stability,” Liang said. He pointed out that the military cooperation is proceeding smoothly in the direction of military supply and personnel training and the Chinese assistance is “unconditional”.

China Daily lambasts AfPak

On Wednesday, ahead of Karzai’s meeting with Chinese President Hu Jintao, the government-owned China Daily featured a devastating critique of the US’s AfPak policy in an article titled “Afghanistan reflects US’ self-obsession”.

The commentary said:

It is clear that the US would like to maintain its influence over Afghanistan even after withdrawing its troops, no matter when that happens. Which means it would not allow regional powers such as China to play a greater role in Afghan affairs. Instead, what the US is willing to share with countries like China is the burden of economic reconstruction.

The commentary harped on differences in the “basic stances” of China and the US. First, the US has adopted a differentiated approach toward terrorism insofar as its focus is on preventing Taliban or al-Qaeda from threatening its homeland security or US’s facilities and personnel. On the contrary, “China, as Afghanistan’s neighbor, also needs to tackle non-traditional security threats such as drug trafficking, arms smuggling and other cross-border crimes,” China Daily said.

Second, the US’s “consolidation” of its military presence in Central and South Asia” on the pretext of the Afghan war “put extra pressure on China’s defense and security interests”.

Third, the US and Chinese economic interests clash. “America gets priority in project selection … And its economic input is aimed at paying for its military operations,” while Chinese enterprises face unfair competition in securing contracts and are vulnerable to security threats.

Fourth, the US is prescriptive and has been “trying to force its political model on the backward country. On the other hand, China believes the Afghans (of all ethic groups and political parties) should decide on what form of government they want based on their culture, tradition and domestic conditions.”

Fifth, China Daily said the US and China are pursuing contradictory “geopolitical objectives”. The US has an “offensive counterterrorism strategy in which Afghanistan is being used as a pawn to help it maintain its global dominance and contain its competitors. China, on the contrary, pursues a defensive national defense policy and wants to have good relations as neighbors of Afghanistan.”

Looking ahead, the commentary said:

The chaos caused by the war in Afghanistan is threatening security in China’s northwestern region. A weak government in Kabul could mean a poorly manned border, which in turn would facilitate drug trafficking and arms smuggling and allow “East Turkmenistan” separatists to seek shelter in Afghanistan after causing trouble in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region.

China should get more countries to come together to resolve the Afghan problem. … The SCO [Shanghai Cooperation Organization] could play a more active role because five of Afghanistan’s six neighbors are its members or observers. … But given the present situation in Afghanistan, an SCO-led reconciliation and reconstruction process is an unrealistic proposition. Hence at present it [China] could only provide help through multilateral channels.

A show of support for Karzai

On the eve of Karzai’s departure for Beijing, he received a delegation from the opposition Hizb-i-Islami group headed by Gulbuddin Hekmatyar. Washington is ambivalent about Hekmatyar, but in the joint statement issued after Karzai’s visit, Beijing expressed support for the reconciliation and reintegration process in Afghanistan and affirmed “respect for the Afghan people’s choice of development road suited to their national conditions”.

Ahmadinejad’s consultations in Kabul, followed by Karzai’s dash to Islamabad, and now his visits to Beijing and Tehran – the sudden spurt of high level exchanges suggest a pattern.

What should alarm Washington most is that the Chinese position on Afghan national reconciliation meshes with Karzai’s political agenda and accords with Iran’s overlapping concerns and interests.

The China-Afghan joint statement affirms Beijing’s readiness to expand economic cooperation, trade and investment while upholding the principle of “respect for the Afghan people’s choice of development road suited to their national conditions”.

Washington will factor in that it is quite within China’s financial capacity to reduce Karzai’s dependence on Western largesse, in turn encouraging the Afghan leader to shake off the West’s attempts to dominate him.

The US-government funded media speculated that during his stay in Beijing, Karzai might seek Chinese investment in Afghanistan’s vast reserves of minerals such as the rich gas fields in the northwestern region bordering Turkmenistan, which is already connected by a pipeline to Xinjiang.

It cannot be lost on Washington that Beijing and Tehran share similar concerns on almost all core areas of the Afghan situation.

These include their perspectives regarding the US’s “hidden agenda” in the Afghan war and therefore the urgency of stabilizing the Afghan situation, Washington’s double standards in the fight against terrorism, the West’s hegemonistic approach toward Afghanistan, the imperative need of “Afghanization” including an Afghan-led national reconciliation, and most important, the desirability of cooperation among like-minded countries in the region in the search for an Afghan settlement.

Conceivably, Beijing’s worries over the critical security situation in Afghanistan and its commonality of interests with Tehran could well act as an additional factor hardening Beijing’s stance apropos the Iran nuclear issue.

Equally, does the prospect of long-term strategic ties between the US and Pakistan worry China?

A senior advisor to the former Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif wrote recently, “Strategic relations with the US may well impinge on other vital linkages. Two are critical. With the US determined to engineer a ‘regime change’ in Iran, what would its expectations be from Pakistan? Finally, can we [Islamabad] contemplate cooperating with the US in any initiative that could trouble our relations with China?”

For the present, the Chinese commentaries seem to take a detached view. They tend to view the US-Pakistan long-term strategic partnership project as a pragmatic move on both sides – borne out of Washington’s need to solicit Pakistani help to stabilize Afghanistan on the one hand and on the other hand Islamabad’s need of US help to resuscitate its economy and to maintain a strategic balance vis-a-vis India.

But Beijing cannot be oblivious of the underlying US regional strategy to frustrate China’s efforts to gain access routes to the Persian Gulf region via Central Asia bypassing the Malacca Strait, which is effectively under American control. The US strategy cannot work unless Pakistan falls in line.

Beijing’s (and Tehran’s) show of support for Karzai comes at a time when his relations with the US and Pakistan are somewhat rocky, to say the least.

Ambassador M K Bhadrakumar was a career diplomat in the Indian Foreign Service. His assignments included the Soviet Union, South Korea, Sri Lanka, Germany, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Uzbekistan, Kuwait and Turkey.