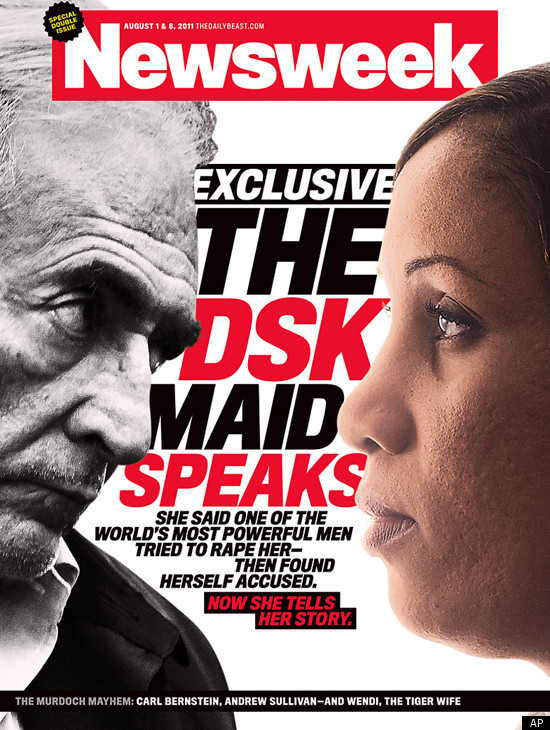

The Maid’s Tale

She was paid to clean up after the rich and powerful. Then she walked into Dominique Strauss-Kahn’s room—and a global scandal. Now she tells her story.

Nafissatou Diallo Interviews: Dominique Strauss-Kahn Accuser Speaks

The hotel maid who accused former IMF head Dominique Strauss-Kahn of rape has broken her silence with a pair of interviews — one for this week’s edition of Newsweek and another with ABC’s Robin Roberts, set to air on Monday’s “Good Morning America” and then “World News with Diane Sawyer” and “Nightline.”

Both are the first mainstream news outlets to publicly name DSK’s accuser — Sofitel maid Nafissatou “Nafi” Diallo, 32, of Guinea.

In a three-hour long interview, Diallo recounted to Newsweek what took place on the day of her alleged attack. She said Strauss-Kahn was standing naked in his room when she knocked on his door.

“Hello? Housekeeping.” Diallo looked around the living room. She was standing facing the bedroom in the small entrance hall when the naked man with white hair appeared.“Oh, my God,” said Diallo. “I’m so sorry.” And she turned to leave. “You don’t have to be sorry,” he said. But he was like “a crazy man to me.” He clutched at her breasts. He slammed the door of the suite.

5-foot-10 Diallo worried about hurting Strauss-Kahn and told him, “Sir, stop this. I don’t want to lose my job,” ultimately running from the room “spitting” after supposedly refusing the French politician’s advances.

And what of the future? Diallo told ABC News, “I want justice. I want him to go to jail. I want him to know that there is some places you cannot use your money, you cannot use your power when you do something like this.”

She added, “God is my witness I’m telling the truth. From my heart. God Knows that. And he knows that.”

According to AFP, Strauss-Kahn’s lawyers have slammed Diallo’s legal team, accusing her attorneys of having “orchestrated an unprecedented number of media events and rallies to bring pressure on the prosecutors in this case after she had to admit her extraordinary efforts to mislead them.”

They also claim Diallo’s broken silence is meant to “inflame public opinion against a defendant in a pending criminal case.”

Diallo’s case against Strauss-Kahn is in jeopardy after prosecutors questioned her credibility. Strauss-Kahn has repeatedly asserted that he’s innocent.

It was even reported that Diallo could face criminal prosecution for allegedly making misleading statements

“Hello? Housekeeping.”

The maid hovered in the suite’s large living room, just inside the entrance. The 32-year-old Guinean, an employee of the Sofitel hotel, had been told by a room-service waiter that room 2806 was now free for cleaning, “Hello? Housekeeping,” the maid called out again. No reply. The door to the bedroom, to her left, was open, and she could see part of the bed. She glanced around the living room for luggage, saw none. “Hello? Housekeeping.” Then a naked man with white hair suddenly appeared, as if out of nowhere.

That’s how Nafissatou Diallo describes the start of the explosive incident on Saturday, May 14, that would forever change her life—and that of Dominique Strauss-Kahn, the managing director of the International Monetary Fund and, until that moment, the man tipped to be the next president of France. Now the woman known universally as the “DSK maid” has broken her public silence for the first time, talking for more than three hours with NEWSWEEK at the office of her attorneys, Thompson Wigdor, on New York City’s Fifth Avenue.

“Nafi” Diallo is not glamorous. Her light-brown skin is pitted with what look like faint acne scars, and her dark hair is hennaed, straightened, and worn flat to her head, but she has a womanly, statuesque figure. When her face is in repose, there is an opaque melancholy to it. Working at the Sofitel for the last three years, with its security and stability, was clearly the best job she’d ever hoped to have, after years braiding hair and working in a friend’s store in the Bronx as a newcomer from Guinea in 2003.

Diallo cannot read or write in any language; she has few “close friends,” she says, and some of the men she has spent time with, whom she does not call fiancés or boyfriends, but “just friends,” appear to have taken advantage of her. One, now in a federal detention center in Arizonaawaiting deportation after a drug conviction, won her confidence—and, she says, access to her bank accounts—by giving her fake designer bags: “Six or seven of them,” she says. “They weren’t very good.” Her face goes almost blank. “He was my friend that I trust—that I used to trust,” she says.

Some of Diallo’s most upbeat moments in the interview came when she recounted the small promotions and credits available at the Sofitel for a job done well. She was supposed to clean 14 rooms a day for a wage of $25 an hour plus tips, according to her union. It’s an achievement, Diallo said, to get a whole floor of your own because it saves the time wasted going up and down in the elevator to clean random individual rooms. Another maid had gone on maternity leave in April, Diallo said, and she’d gotten the 28th floor. “I keep that floor,” said Diallo. “I never had a floor before.” When every door has a “Do Not Disturb” notice, maids save precious minutes by going to the hall closet and quickly refilling their cleaning carts with soap, towels, and other amenities. Diallo’s eyes lit up talking about the routine and about her colleagues. “We worked as a team,” she said. “I loved the job. I liked the people. All different countries, American, African, and Chinese. But we were the same there.”

Occasionally as Diallo talked, she wept, and there were moments when the tears seemed forced. Almost all questions about her past in West Africa were met with vague responses. She was reluctant to talk about her father, an imam who ran a Quranic school out of the family home in rural Guinea. Her husband died of “an illness,” she said. So did a daughter who was 3 or 4 months old—she wasn’t sure. Diallo was raped by two soldiers who arrested her for a curfew violation at night in Conakry, the Guinean capital. When they had finished with her, they released her the next morning, she said, but made her clean up the scene of the assault. At first she said she couldn’t recall what year that happened, but later she said it was 2001. Diallo had managed to get her surviving daughter, now 15, out of Africa and to the United States “for a better life,” she said. But precisely how that happened was not a subject she or her lawyers would explore. Again, her eyes stared downward, welling with tears.

When Diallo reached the point of her alleged assault in the Sofitel, however, her account was vivid and compelling. As she told NEWSWEEK, she had used up a lot of time waiting for guests to check out of room 2820 before she cleaned it. Then she saw the room-service waiter taking the tray out of 2806, one of the hotel’s presidential suites. The waiter said it was empty. But still she decided to check. This is her account.

“Hello? Housekeeping.” Diallo looked around the living room. She was standing facing the bedroom in the small entrance hall when the naked man with white hair appeared.

“Oh, my God,” said Diallo. “I’m so sorry.” And she turned to leave. “You don’t have to be sorry,” he said. But he was like “a crazy man to me.” He clutched at her breasts. He slammed the door of the suite.

Diallo is about 5 feet 10, considerably taller than Strauss-Kahn, and she has a sturdy build. “You’re beautiful,” Strauss-Kahn told her, wrestling her toward the bedroom. “I said, ‘Sir, stop this. I don’t want to lose my job,’” Diallo told NEWSWEEK. “He said, ‘You’re not going to lose your job.’” An ugly incident with a guest—any guest—could threaten everything Diallo had worked for. “I don’t look at him. I was so afraid. I didn’t expect anyone in the room.”

“He pulls me hard to the bed,” she said. He tried to put his penis in her mouth, she said, and as she told the story she tightened her lips and turned her face from side to side to show how she resisted. “I push him. I get up. I wanted to scare him. I said, ‘Look, there is my supervisor right there.’” But the man said there was nobody out there, and nobody was going to hear.

Diallo kept pushing him away: “I don’t want to hurt him,” she told us. “I don’t want to lose my job.” He shoved back, moving her down the hallway from the bedroom toward the bathroom. Diallo’s uniform dress buttoned down the front, but Strauss-Kahn didn’t bother with the buttons, she said. He pulled it up around her thighs and tore down her pantyhose, gripping her crotch so hard that it was still red at the hospital, hours later. He pushed her to her knees, her back to the wall. He forced his penis into her mouth, she said, and he gripped her head on both sides. “He held my head so hard here,” she said, putting her hands to her cranium. “He was moving and making a noise. He was going like ‘uhh, uhh, uhh.’ He said, ‘Suck my’—I don’t want to say.” The report from the hospital where Diallo was taken later for examination notes that “she felt something wet and sour come into her mouth and she spit it out on the carpet.”

“I got up,” Diallo told NEWSWEEK. “I was spitting. I run. I run out of there. I don’t turn back. I run to the hallway. I was so nervous; I was so scared. I didn’t want to lose my job.”

Diallo says she hid around the corner in the hallway near the service lobby and tried to compose herself. “I was standing there spitting. I was so alone. I was so scared.” Then she saw the man come out of 2806 and head for the elevator. “I don’t know how he got dressed so fast, and with baggage,” she said. “He looked at me like this.” She inclin-ed her head and stared straight ahead. “He said nothing.”

The entire incident had taken no more than 15 minutes, and maybe much less. According to a source familiar with the phone records, nine minutes after Diallo entered the room, Strauss-Kahn made a call to his daughter.

The maid had left her cleaning supplies in room 2820 when she went to check on Strauss-Kahn’s suite. Now she retrieved them and returned to the suite in which, she says, she had just been attacked. Disoriented, she seems to have sought some kind of solace in resuming her routine. “I went to the room I have to clean,” she explained. But she couldn’t think how or where to start. “I was so, so, so—I don’t know what to do.” Prosecutors, losing faith in Diallo’s credibility, would later raise an issue about this sequence of events. They said she told the grand jury that after the attack she hid in the hallway, but subsequently changed her story to say she cleaned room 2820 and then began to clean the DSK suite. She disputes that she changed her story, and hotel room-access records support what she told NEWSWEEK.

Many aspects of Diallo’s account of the alleged attack are mirrored in the hospital records, in which doctors observed five hours afterward that there was “redness” in the area of the vagina where she alleges Strauss-Kahn grabbed her. The medical records also note she complained of “pain to left shoulder.” Weeks later, doctors reexamined the shoulder and found a partial ligament tear, she said.

If there is one inconsistency for defense lawyers to dwell on in the hospital records, it is a passage that says her attacker got dressed and left the room, and “said nothing to her during the incident.” In her interview with police and her account to NEWSWEEK, Diallo recalled several statements Strauss-Kahn made during the alleged attack.

Defense lawyers are expected to challenge the nature of her injuries, her recollection of events, the veracity of elements of her life story, and her conduct with other men if the case proceeds.

Diallo’s supervisor, making the rounds, found her in the hallway. She could see Diallo was shaken and upset and asked what was wrong. “If somebody try to rape you in this job, what do you do?” Diallo asked her. The supervisor was angry when she heard of the assault, Diallo recalled. “She said, ‘The guest is a VIP guest, but I don’t give a damn.’” Another supervisor came, then two men from hotel security. One of them told Diallo, “If this was me, I would call the police.” At about 1:30 p.m., an hour after the first supervisor was told of the alleged attack, the hotel dialed 911.

At that moment, Dominique Strauss-Kahn was still one of the most powerful men in the world. As head of the IMF, he was the lead player in attempts to keep the European, and indeed the global, economy from plunging into a potentially apocalyptic recession. He was also getting ready to declare his candidacy for the presidency of France in an election only a year away. If he were to defeat Nicolas Sarkozy, the hugely unpopular incumbent, DSK would then govern a country that is a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council and has the world’s third-biggest arsenal of nuclear weapons.

Prosecutors have identified a hotel concierge who says DSK made an unwanted advance to her the previous night. They have also identified a blonde American businesswoman observed going into the same elevator as Strauss-Kahn at 1:26 a.m. in what appears to have been a consensual relationship. (The French magazine Le Point reported implausibly in July that Strauss-Kahn had even admitted to his wife, the heiress and former television personality Anne Sinclair, that he had had sex with three women that Friday and Saturday as “a last glass before hitting the road for the [French] presidential campaign.”)

What’s more certain is that after checking out of the hotel at 12:28 p.m. on May 14, Strauss-Kahn went to lunch with his youngest daughter, Camille, who had been studying at Columbia University. From there, he went to JFK airport to catch Air France Flight 23 overnight to Paris. The next day he was supposed to meet with German Chancellor Angela Merkel. But as he waited to board the plane, Strauss-Kahn apparently couldn’t find his IMF cell phone. On another mobile, he called the Sofitel to ask if it had been found in the suite. The police, now on the scene at the hotel, had an employee say yes (although in fact the phone was not there) and ask where they could get it to him. The Air France terminal, Gate 4, he said, and asked them to rush to get it to JFK before takeoff. Instead, the Port Authority police were notified, and just before the plane was ready to taxi away from the gate, they took Strauss-Kahn off it. “The NYPD need to speak with you about an incident in the city at a hotel,” one of the cops told him.

While Strauss-Kahn languished in “the box,” the interview room at the Manhattan Special Victims Squad in Harlem, Nafissatou Diallo was taken to the hospital for examination, then back to the hotel with the police to walk through what had happened to her, showing them where she stood, where she fell, where she spit. As the day wore on, she became increasingly frantic about her daughter alone at home. Finally the police took her back to the Bronx at 3 in the morning. Neither she nor the girl could sleep. “She was so scared,” Diallo remembered.

But when Diallo watched the morning news, she was terrified: “I watched Channel 7 and they say this is [the] guy—I don’t know—and he is going to be the next president of France. And I think they are going to kill me.” The phone started to ring in her apartment as reporters found her number. Others appeared at her door. She woke her daughter and told her to pack her bag and get ready to stay with a relative. She told the girl how powerful DSK must be: “Now everybody say everything about me, all the bad things.” The girl tried to reassure her mother. “She says, ‘Please, Mom, don’t hurt yourself. I know one day the truth will come out.’ I was so happy when she said that.”

That afternoon, Diallo went back to the Special Victims Squad to look at a lineup of five men. “My heart was like this,“ she says, patting her chest. But she knew him immediately. “No. 3,” she said, and left as quickly as she could. Later she was housed in a hotel with her daughter for weeks, almost incommunicado, neither of them allowed cell phones after they were placed in protective custody by prosecutors. It would be almost two months before she was allowed to return to her apartment to pick up her possessions. “I don’t know why I have to do these things,” she says. “Is it because he is so powerful?”

To this day, we do not have DSK’s account of what happened in suite 2806. Since his arrest, Strauss-Kahn has shielded himself with highly skilled lawyers and investigators who have kept his version of events off the public record. His lawyer, William Taylor, told NEWSWEEK, “What disgusts me is an effort to pressure the prosecutors with street theater, and that is fundamentally wrong.” To charges of criminal sexual assault, attempted rape, and related offenses, Strauss-Kahn entered a plea of not guilty. Meanwhile, his supporters have attacked the maid’s account, her reputation, her background, and her associations. But Strauss-Kahn’s antecedents surfaced with a vengeance as well.

In 2008 DSK admitted to an affair with a subordinate at the IMF. Speaking to investigators, he called it “a personal mistake and a business mistake.” In July a young French journalist and novelist, Tristane Banon, filed charges against him in Paris for what she claims was an attempted rape in a Left Bank apartment where she went to interview him in 2003. She told fellow guests during a TV appearance in 2007 that he had come after her like “a chimpanzee in rut,” and her account bears some similarities to Diallo’s as she describes a man who seems to lose control completely when at the height of sexual desire. Banon’s mother, Anne Mansouret, is an ambitious politician in her own right who is often identified with Strauss-Kahn’s rivals in the French Socialist Party. She recently claimed that she herself had had consensual but “brutal” sex with him in 2000. Among DSK’s acquaintances from Paris to Washington to New York, dinner-party conversation is rife with tales of close calls and wild encounters. One French magazine calls him “Dr. Strauss and Mr. Kahn.” He also has long enjoyed a reputation as being hugely charming and seductive.

DNA evidence in suite 2806—the result of all that spitting that mingled the maid’s saliva and Strauss-Kahn’s sperm—makes it virtually impossible to deny there was a sexual encounter between DSK and Diallo. Strauss-Kahn’s lawyers raised the possibility early on that it was consensual and have left it to others to speculate about the circumstances under which that might have been the case: that Diallo expected money that she did not receive, or that the sex got rougher and more aggressive than she would accept. The New York Post published stories attributed to an anonymous source that claimed Diallo was at least a part-time prostitute. Her lawyers, Kenneth Thompson and Douglas Wigdor, are now suing the Post, saying the story is false. The newspaper stands by its story.

In her interview with NEWSWEEK, Diallo didn’t disguise her anger at Strauss-Kahn. “Because of him they call me a prostitute,” she said. “I want him to go to jail. I want him to know there are some places you cannot use your power, you cannot use your money.” She said she hoped God punishes him. “We are poor, but we are good,” she said. “I don’t think about money.”

Perhaps. But on the day of the incident, by Diallo’s own account, she made two telephone calls. One was to her daughter. The other call was to Blake Diallo, a Senegalese who is from the same ethnic group but no relation. He manages a restaurant, the Cafe 2115 in Harlem, where West Africans gather to eat, talk, politic, and sometimes listen to concerts. Nafissatou describes Blake as “a friend,” and one of the first things he did for her after the incident was to find her a personal-injury lawyer on the Internet.

More problematic were a series of phone calls that Nafissatou Diallo received from Amara Tarawally, whose uncle owned the bodega where Diallo worked when she first came to the United States. Originally from Sierra Leone, he divided his time between New York and Arizona, where he sold T shirts and fake designer handbags. But last year he was busted in a sting operation run by Arizona police when, according to cops, he paid them almost $40,000 cash for more than 100 pounds of marijuana.

On July 1, The New York Times reported the existence of a taped conversation between Diallo and Tarawally. The article said they talked the day after the incident at the Sofitel and quoted a “well-placed law enforcement official”: “She says words to the effect of, ‘Don’t worry, this guy has a lot of money. I know what I’m doing.’” But at the time, prosecutors did not have a full transcript of the call, which had been conducted in a dialect of Fulani, Diallo’s language. The quote was a paraphrase from a translator’s summary of the tape, and the actual words are somewhat different, sources told NEWSWEEK.

In July NEWSWEEK talked to Tarawally in Arizona. He insisted that the quotation must refer to a later conversation and in any case was taken out of context. Diallo said she no longer talks to Tarawally. He used her bank account to move tens of thousands of dollars around the country without informing her, she said. She denied he ever gave her money to spend. “Like I say, he was my friend,” Diallo told us. “I used to trust him.”

But the list of reasons for prosecutors to doubt Diallo’s credibility does not begin or end with Tarawally. In a letter to DSK’s defense lawyers on June 30, Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus Vance Jr. cited several lies and deceptions in her past. She had claimed deductions for two children on her taxes instead of one. She had understated her income to get cheaper housing. And, most important, she had lied on her asylum application.

Diallo, a widow, came to the United States in 2003, leaving her then–7-year-old daughter behind in Guinea with a brother. Having entered the U.S. under dubious circumstances and without working papers, she lived with family members for some time, eking out an income braiding hair and then working in a bodega in the Bronx.

In late 2003 Diallo applied for asylum. Because she had suffered genital mutilation as a child, and doctors confirmed that fact in a medical report, she probably would have qualified for asylum in any case, given current law and practices. And she insists she was raped after curfew by two soldiers. (This is not unheard of in Guinea. In 2009 soldiers conducted mass rapes and killed as many as 160 people in a Conakry sports stadium, according to human-rights organizations.) But bad as the realities were in Diallo’s homeland, she admits the account that she gave the U.S. government on her asylum application was heavily embellished. Her fictionalized narrative worked to get her a green card and allow her to bring her child to America. But her past misstatements may make it impossible to win a criminal case against DSK based on her testimony.

Prosecutors are likely weeks away from making a decision on whether to proceed with the -charges. They remain confident that the forensic evidence shows a sexual encounter and impressed by the consistency of the story Diallo told to two maid supervisors, two hotel security guards, hospital personnel, and detectives during the first 24 hours. The prosecution team has “no idea what it is going to do yet,” a person close to the case said. The investigators are “treating it like any other case that runs into these problems, and that means gathering all the evidence.”

Given the issues of Diallo’s credibility, investigators have been building a “suspect profile” of DSK, interviewing other women who claim to have been assaulted or who had consensual affairs, trying to establish a pattern of behavior and comparing it to Diallo’s account. In mid-July they talked with the lawyer for Tristane Banon. Though not required to do so, New York prosecutors have begun the process of asking French authorities to let her speak to U.S. officials, providing the alleged victim some political cover in her home country, where the DSK case is a media rage.

Almost immediately after the indictment was secured and long before the public knew of the problems with Diallo’s past, prosecutors began digging around in her financial records and interviewing friends, looking for any evidence of extortion or criminal activity. The review found ties to shady acquaintances and suspicious transactions, to be sure, but no evidence of a premeditated plot against Strauss-Kahn.

It’s possible that Diallo is a woman who has lived for the last few years on the margins of quasi-illegal immigrant society in the Bronx, associating with petty con artists and dubious types trying to get a foothold in this country. But that does not preclude her having been the victim of a predatory and powerful man. Nor does it mean she will rule out an attempt to make some money from the situation.

Given the climate of suspicion that developed around her, Diallo’s last three encounters with authorities, on June 8, 20, and 28, were difficult sessions, as prosecutors grilled her like a defendant. The mistrust between Vance and Diallo’s lawyers boiled over on July 1, when Thompson held a news conference in front of the courthouse and accused the district attorney of abandoning Diallo.

Since then, both sides have tried to smooth matters over. Thompson has signaled a willingness to let his client be interviewed again if prosecutors let her see a transcript of the disputed prison call, and that is something prosecutors say they are willing to do. But the distrust and tensions could be renewed again after prosecutors learn of Diallo’s decision to go public after weeks of remaining in protective custody. Diallo says she gave the interview to NEWSWEEK to correct the misleading portrayal of her in the media. Her account of what happened has remained the same all along, she says. “I tell them about what this man do to me. It never changed. I know what this man do to me,” she says.

Looking to the future, Diallo says she would love to go back to working in a hotel, but maybe in the laundry. She wants never again to have to knock on a door and call out: “Hello? Housekeeper.”