Who Runs the Fed?

Timothy A. Canova ? Summer 2015

The 2008 financial crisis challenged many orthodox assumptions in finance and economics, including the proper role and accountability of central banks. The U.S. Federal Reserve, commonly known as the Fed, is the world’s most powerful central bank.

One major source of Federal Reserve power is its role as “lender of last resort,” lending directly to commercial banks through its so-called discount lending window. Traditionally, only commercial banks had access to the Fed’s discount lending since non-bank financial institutions were not subject to the same reserve and capital requirements as those imposed on banks. The other major source of the Fed’s power is its ability to purchase short-term Treasury securities. These restrictions on Fed lending and asset purchases helped support the central bank’s political independence from Congress and the White House by ensuring that Fed policy was socially neutral and did not favor particular sections of financial markets or particular private constituencies. But as the Federal Reserve’s lending and asset purchase powers expanded in unprecedented ways in 2008, these traditional restrictions were swept aside, exposing the flaws of central bank independence.

The Fed is also able to create money—U.S. dollars, also known as Federal Reserve notes—which means there is virtually no limit to the amount of money it can lend and no limit to the volume of assets it can purchase without adding to public-sector borrowing or deficits. During the 2008–2009 financial crisis, the Fed extended more than $16 trillion in low interest loans to all kinds of financial institutions in distress, including borrowers who traditionally lacked access to its discount window such as hedge funds and foreign commercial banks and central banks. Also, beginning in 2008, the Fed launched several asset purchase programs, known as “quantitative easing” (or QE), to purchase more than $3.5 trillion in U.S. Treasury securities and mortgage-backed securities (MBS).

But this expansion of the money supply is deceiving. Instead of lending out the funds pumped in by the Fed, banks have added more than $2.6 trillion to their excess reserves, on which the Fed has also paid them interest. This is similar to what happened during the Great Depression. Much of the money the Fed pushed into the banking system has not trickled down to the real economy.

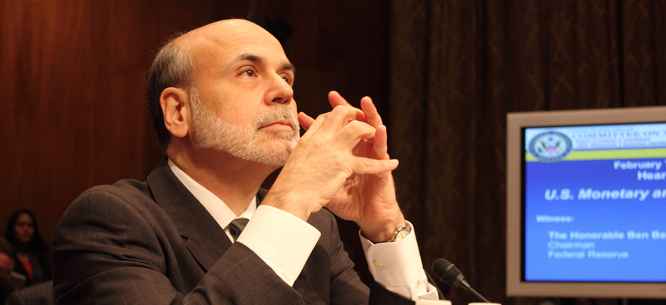

Ben Bernanke, the Federal Reserve chairman when the QE programs were first launched, claimed that asset purchases would have a “wealth effect”: by the Fed purchasing bonds in such large amounts, bond prices would rise, yields would fall, and investors would shift into riskier securities, driving up the price of corporate shares and stock markets. Everyone would feel richer, businesses would invest and consumers would spend more. This seems much like the theory of “trickle-down” fiscal policy: that tax cuts for those with high incomes would be invested, thereby leading to the hiring of additional workers and spreading the benefits to the rest of the economy. But like the Bush administration’s tax cuts, the Fed’s monetary trickle-down has not worked so well. The Fed’s lending and asset purchase programs have effectively propped up Wall Street interests—big banks and financial markets—but they have also neglected the needs of Main Street, including the small community banks, small and moderate sized and family-owned businesses, unemployed and underemployed workers, and state and local governments.

The Federal Reserve’s response to the 2008 crisis is quite different from its “bottom up” approach in the Great Depression in the 1930s when it extended credit directly to Main Street businesses. Section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act allowed the Fed to lend directly, not just to big banks, but also to “individuals, partnerships, and corporations” in “unusual and exigent circumstances.” Another provision, section 13(b) (since repealed in 1958) authorized the Fed to make credit available for “working capital to established industrial and commercial businesses” with permissible maturities of up to five years and “without any limitations as to the type of security” for collateral. In total, the Fed made about $280 million available to small- and moderate-sized businesses. That was about 0.43 percent of GDP at the time, or about $65 billion in today’s terms.

In contrast, in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, the Federal Reserve has consistently rejected proposals to lend directly to Main Street, including proposals for loans to state infrastructure banks, to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac (two government supported entities that hold trillions of dollars in mortgages), to modify underwater mortgages, and to students to refinance their debts. Throughout, Fed officials have taken the view that they lack the legal authority for such lending and in particular, that federal law requires there be “good collateral” for any such loans.

However, such requirements did not stop the Federal Reserve from lending $29 billion to JPMorgan Chase to purchase Bear Stearns in March 2008, secured only by Bear Stearns’ shaky mortgage-related assets. This led Paul Volcker, a former Fed chairman, to express concern that the Fed’s intervention was testing the limits of its lawful powers and would call into question the Fed’s political independence if the central bank were viewed “as the rescuer or supporter of a particular section of the market,” such as mortgage-backed securities, collateralized debt obligations (CDOs), and other exotic financial instruments. Volcker warned that such allocation decisions are inherently political—“not strictly a monetary function in the way it’s been interpreted in the past”—and are more properly made by the elected branches of government as fiscal policy.

Yet, throughout 2008–2009, the Fed expanded its lending well beyond its traditional statutory authority, including to primary dealers in U.S. Treasury securities and foreign exchange swap lines for foreign central banks. The Fed effectively lent them more than a trillion U.S. dollars in exchange for a specified amount of their currencies until they were able to return those dollars for their currencies at the same exchange rate. The Fed also lent more than $700 billion to a facility of its own creation, a “special purpose entity,” to purchase commercial paper directly from major corporate borrowers, which helped prop up big businesses and cartels while ignoring the small and moderate-sized businesses and family enterprises that give life to Main Streets across the country. It was clear that the courts and political branches of government would not interfere with the Fed’s determination of what constitutes good collateral and the scope of its lawful powers in “unusual and exigent circumstances,” particularly when helping Wall Street in a crisis.

The Federal Reserve expanded its support for Wall Street in other unconventional ways that also suggested a bias in favor of the private financial interests that sit on the Fed’s own governing boards. In the fall of 2008, the Fed made an emergency equity investment in American International Group (AIG), taking a 79.9 percent interest in the global insurance conglomerate, all to make sure that AIG continued paying off on its credit default swaps (CDS) to Goldman Sachs and other counterparties. These swaps provided insurance against a downturn in the housing and mortgage markets. However, they also allowed Goldman Sachs and other speculators to bet against the same toxic mortgage-backed securities that they had created and already sold off to unsuspecting clients and investors. By rescuing AIG, an extraordinary measure that tested the limits of its authority, the Fed was no longer simply the lender of last resort: it was now the “buyer, dealer, and gambler of last resort,” serving as the gambling house to prop up the market for derivative contracts and to cover the wagers and losses of the global casino.

Goldman Sachs and other giant banks and hedge funds have engaged in similar shady and speculative activities abroad, for instance, betting on Greek, Spanish, and Italian sovereign and private debt. Through the use of derivatives, Goldman Sachs shorted the same Greek debt that it had previously helped the Greek government hide through other derivatives, namely currency swaps that allowed Greece to swap debt it had issued in dollars and yen for euros, using an outdated exchange rate that implied a reduction in debt. The European Central Bank (ECB) and International Monetary Fund (IMF) assured that these speculators would be paid off on their bets. Along with JPMorgan Chase and other big banks, Goldman Sachs would then take advantage of the austerity imposed on Greece and other countries by setting up infrastructure funds to buy up state-owned assets in fire sale privatizations.

Unlike the Federal Reserve’s lending programs, which have at least a semblance of statutory guidelines, the Fed has more discretion in its asset purchase programs, which have made a longer lasting effort at trickle-down monetary policy. In the first QE program, which began in November 2008, the Fed purchased $1.25 trillion in mortgage-backed securities, $300 billion in Treasury securities, and $200 billion in Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac “agency debt,” all with money newly created by the Fed. The Fed was no longer just taking distressed mortgage bonds as collateral on loans, which had been Volcker’s concern, it was now actually purchasing more than a trillion dollars in these assets.

When this QE program ended, the U.S. economy once again slowed. The financial markets had become addicted to the Fed’s massive bond purchases and when each QE ended, the markets needed another fix. The Fed responded in November 2010 with QE2 to purchase an additional $600 billion in Treasury securities. Next came “Operation Twist” a year later, in which the Fed shifted some of its portfolio of Treasury securities from short-term to long-term maturities, intended to bring down long-term interest rates on other securities and mortgage loans. Finally in September 2012, the Fed announced QE3, an open-ended pledge to purchase $40 billion of agency MBS and $45 billion of long-term Treasury securities each month. QE3 would last nearly two years.

Critics have charged the QE approach with pumping up financial markets, creating new bubbles, ignoring the needs of real people and Main Street businesses, and weakening the currencies of countries following the approach, thereby impairing growth in other nations. Yet, the Fed’s QE programs have become the model for other major central banks. Beginning in March 2009, the Bank of England purchased about $569 billion in assets, in at least three rounds, increasing the total each time the effect of the previous round wore off. As the Fed was tapering off its QE3 purchases, the Bank of Japan launched its own QE program of $1.4 trillion in asset purchases. More recently, the ECB announced its QE program of $69 billion a month in public and private bond purchases, to total more than $1.3 trillion.

Many central bankers were aware of the limited effectiveness of these QE programs, but supported them nonetheless in the absence of any ongoing fiscal stimulus. Although Ben Bernanke, the Fed chairman at the time, was calling on the government to do more on the fiscal policy side, extension of Bush’s tax cuts was the trickle-down approach he most favored and which was accepted by the Obama administration through 2012.

In helping Wall Street and global capital markets, the Fed has stretched its asset purchasing well beyond its traditional powers. Meanwhile, it has claimed a lack of authority to serve Main Street interests, even on a far lesser scale. For instance, there have been proposals for the Fed to purchase state and municipal bonds to help finance construction and repair of roads and bridges. The Fed presently lacks authority to purchase municipal bonds with maturities of more than six months, so Fed purchases of longer maturities would require congressional action. There have also been proposals for the Fed to pump money into state infrastructure banks, and to purchase student debt and to allow moratoriums on debt repayment while labor markets remain weak. Others have urged the Fed and the ECB to make cash transfers directly to consumers and taxpayers. From both sides of the spectrum came proposals for mortgage loan modifications, financed either directly by the Fed or by the Treasury with Fed support. These kinds of QEs for Main Street, like the Fed’s QEs for Wall Street, would incur no costs to government and would not add to deficits; quite the contrary, since they would put taxpaying resources back to work. Such monetary policies would have prodded the United States and the Eurozone away from austerity and in the direction of full employment.

Why help Wall Street creditors and not Main Street debtors? Why purchase trillions of dollars of mortgage-backed securities from banks, but not help the actual homeowners who are upside down on their mortgages? With the QE approach, central banks are picking winners and losers in the marketplace, which should raise concerns about both their social neutrality and their political independence. In criticizing the proposed Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) agreement, Senator Elizabeth Warren has noted that a rigged process inevitably leads to rigged outcomes. It is much the same with the Federal Reserve, which is captured by big banking interests and rigged by design. Not surprisingly, the Fed also fosters rigged outcomes.

Although the Federal Reserve claims that its allocation decisions are disinterested, a review of its governance structure may suggest otherwise. The public face of the Fed is the chairman of its Board of Governors in Washington, D.C. For nearly two decades that was Alan Greenspan, who came to the Fed through the “revolving door” from Wall Street, where he had been a director at JPMorgan. Ben Bernanke, formerly the chief economics advisor in the Bush White House, was Fed chairman from 2006–2014, during the peak of the financial crisis, and was also the architect of the Fed’s massive lending and asset purchase programs. Janet Yellen, who became Fed chair in 2014, was president of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco during the bubble and embraced Bernanke’s QE strategies since first becoming the Fed’s vice chair in 2010. In addition to the Fed chairman and Board of Governors, the Fed’s Open Market Committee (FOMC) and the Federal Reserve Bank of New York (the NY Fed) make many of the key decisions that have helped Wall Street. This is not at all surprising since the FOMC consists of the seven-member Board of Governors along with the presidents of the twelve privately owned regional Federal Reserve banks. The regional Feds are governed by private boards of directors that are dominated both formally and in practice by the private commercial banks that own the shares in these banks. The Fed’s governance structure, like all “independent” central banks, is not all that independent of private financial interests. Rather, these central banks are captured agencies. The fox is running the henhouse.

The Obama administration’s main legislative response to the financial crisis was the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010, which included a provision introduced by Senator Bernie Sanders requiring the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) to conduct unprecedented audits of the Federal Reserve’s governance, monetary policy, and emergency lending programs during the crisis. These audits revealed Fed favoritism of big Wall Street interests with secret emergency loans, including massive support for many of the bankers who sit on the boards of the regional Fed banks. For instance, Jamie Dimon, the CEO of JPMorgan Chase, sat on the board of the NY Fed while his bank received an eighteen-month exemption from risk-based leverage and capital requirements, and $29 billion in financing to acquire Bear Stearns, while the Fed assumed Bear Stearns’ toxic assets, thereby relieving JPMorgan of huge liabilities in the future.

Another GAO audit found serious conflicts of interest in Federal Reserve governance. For instance, in 2008, Stephen Friedman, the chairman of the NY Fed, sat on the board of directors of Goldman Sachs and owned Goldman stock, while the NY Fed was approving Goldman’s application to become a bank holding company to obtain access to the Fed’s low-interest loans. This was also while Friedman chaired the search for a new president of the NY Fed that resulted in the selection of William Dudley, who had recently been a partner and managing director at Goldman and served for a decade as Goldman’s chief U.S. economist.

In September 2010 Reuters published a special investigative report of the Federal Reserve’s selective disclosure of sensitive information about monetary policy to its favored clientele in the private financial sector. Reuters found that private financial analysts and former Fed officials were profiting from their leaked information, possibly in violation of federal law. Moreover, these backroom exchanges appear to be among the many quid pro quos in a system of opaque subsidies and part of a larger problem of private financial influence over economic decision-making by the government. In 2011, the Fed announced certain restrictions on meetings with senior Fed officials. But it is difficult to change the Fed’s culture of revolving doors and cozy relations with private financial institutions. In May 2015, the Fed announced that the U.S. Justice Department was conducting a criminal investigation of a 2012 disclosure of confidential information about a crucial FOMC meeting to Medley Global Advisors, a firm that sells financial analysis to investors, is owned by the Financial Times, and is part of Pearson PLC, a huge multinational publishing and education conglomerate. House Republicans are also pressing for information about the leak and the Fed’s own internal inquiry.

Finally, the Fed’s conflicts of interest have raised questions about the rigor and impartiality of its regulatory supervision and oversight of the biggest banks. For instance, in 2009, the NY Fed commissioned a secret internal investigation of itself conducted by a Columbia University finance professor, which according to the Wall Street Journal, revealed “a culture of suppression and discouraged regulatory staffers from voicing worries about the banks they supervised.” The review recommended various reforms to encourage “critical dialogue and continuous questioning.” Yet, four years later the Fed’s culture was still in question when one of its former bank examiners, Carmen Segarra, filed a lawsuit alleging that the NY Fed had interfered with her oversight of Goldman Sachs. Segarra’s allegations could not be easily ignored since she had secretly recorded audio of some forty-six hours of meetings and conversations with her colleagues and superiors.

The Fed’s governance and independence are often defended by arguments that its current methods help to draw on the expertise of bankers and financiers. But the exclusion of all social groups other than bankers from Fed governance skews the institution’s decision-making. Reforming central bank governance to include a diversity of perspectives and interests could prod the institution into once again supporting public infrastructure and a jobs program.

It would also be worthwhile to break the monopoly of central banks in the issuance of currency by funding some government operations with money created and issued by treasuries and finance ministries—money that would not add a penny to public debt. This is what President Abraham Lincoln did by issuing more than $400 million in U.S. notes, the so-called Greenback, to pay the huge costs of the American Civil War and national economic development programs. A century earlier, colonial Pennsylvania enjoyed fifty-two years of non-inflationary growth by issuing and lending its own currency into circulation, thereby financing major development of infrastructure without incurring debt or high tax burdens. Adam Smith, in his classic work Wealth of Nations (1776), praised Pennsylvania’s success with government-issued money. Such proposals have been introduced in Congress over the years, but Wall Street lobbying has prevented such legislation from passing.

In the United States and elsewhere, the model of central bank independence is built on sand, propped up with trillions of dollars in market interventions designed and implemented by captured central banks. This central bank exception to democracy is not sustainable. It undermines broad-based economic well-being by concentrating power—and therefore wealth and income—in fewer and fewer hands. Any real progressive reform will require making the governing boards and policy-making committees of central banks genuinely inclusive to reflect a wider range of interests and to facilitate a wider discussion on the formulation of monetary policy. The longer reform is delayed, the longer we will have to live with huge redistributions of wealth and income from the many to the few, from Main Street to Wall Street.

***Timothy A. Canova is a professor of law and public finance at Nova Southeastern University’s Shepard Broad College of Law in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. An earlier version of this article was published in Limes, the Italian journal of geopolitics, in February 2015 in a special volume, Money and Empire (Moneta e Impero).