By Tunku Varadarajan

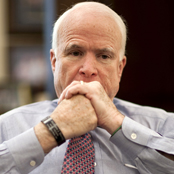

As John McCain heads into Tuesday’s primary fighting tooth and nail against a clownish challenger, Tunku Varadarajan says failing to do the decent thing and call it quits after losing the presidency to Obama turned the maverick into an insecure, reactive hack.

“Barnacle McCain” is the way one might characterize the senior senator from Arizona, now fused so ferociously to the tidal rocks of a fifth term that he will say pretty much anything, no matter how much the utterance is at odds with his older, saner positions, in order to secure his own reelection. All the polls indicate that John McCain will, come Tuesday, knock out J.D. Hayworth, his clownish challenger, in the state’s Republican Senate primaries; and, having done so, it is impossible to see his Democratic opponent beating him in November. Arizona is, after all, the Tea Party writ large. But I do wish that McCain had not fought the primaries as an insecure, reactive, poll-watching hack who focus-groups his way to reelection. From a first-timer, such strategic micro-tailoring would be understandable; from a fifth-timer, the whole exercise seems tawdry, unseemly, yucky.

Conservatives have always found McCain confounding, and infuriating: No one has ever counted him among the more ideological of Republican politicians, his reputation being, instead, that of an “honor” politician who laid great, often gaudy, stress on Doing the Right Thing, on being a “maverick,” a condition that bestowed a certain unpredictable magic on him while at the same time freeing him of ideological taint. McCain gloried in the label, using it to differentiate himself from the rock-ribbed right, a ploy that was successful—and largely credible—until he chose Sarah Palin as his running mate in 2008.

He seems to have taken deeply personal offense at the loss to Obama, and it has weakened him to the point where a Tea Party caricature has forced McCain to spend $20 million to defend his Senate seat.

Adding to conservative consternation with McCain was the fact that much of the American media, ideologically liberal as a tribe and partisan in favor of the Democrats, treated McCain as a “hero” precisely to the extent that he dissented from conservative policies and caused trouble for the Republicans. (He is, after all, the McCain of McCain-Feingold, a law that counts among its fans a certain Barack Obama.) McCain took his biggest wrong turn when he boarded his “Straight Talk Express” and became the media’s darling, always providing pungent copy, always giving them a lead, always sniping and sneering at the “Establishment” and quite unaware that the press adored him because he was useful to them in their own soft-core anti-Americanism. But once he became the Republican standard-bearer in 2008, he became the enemy—and this happened many months before he plumped for Palin. McCain then found himself, for the first time in his political career, to be a politician largely friendless in the media: The so-called mainstream, besotted with Obama, bid McCain an abrupt adieu; and the Fox News right, always ambivalent (at best) about the maverick, tolerated him as the non-Democrat without ever embracing him, its thumb and forefinger held firmly to its nose.

• Midterm Madness: 10 Hot Races to Watch

• Kirsten Powers: The GOP’s Long, Hot, Racist SummerThe decent thing for McCain to have done after Obama’s election would have been to say that he was calling it quits, giving way in the Senate to a politician less spent. But he didn’t. Politicians without a guiding ideology are, frequently, the ones who stay in the game longest. Manic redefinition, constant reorientation, tracking the latest directions on the ideological GPS, places them on an unending trajectory of reelection, a journey that ends only with death. The late Senator Robert Byrd was one such man; McCain, without Byrd’s godawful stains, is shaping to be another. I don’t have reliable data on the topic, so consider this an anecdotal observation, but this is how vainglorious politicians often end their careers—hanging on a little too long, at great cost to their public image. Think of McCain as the Liza Minnelli of American politics.

Ultimately, there is no escape from the McCain bottom line. A colleague of John McCain’s put it this way: What you need to know is that he really does believe in duty, honor, country… and he is an American hero. But he thinks that is all there is. He has no deep interest or principle on any other subject. Every other issue has become personal with him, viewed through politics or pique. He is a patriot for whom most other issues are simply situational, which is why he can change so easily on them.

McCain has conducted himself like a sore and unpleasant loser since his defeat by Obama, without ever plumbing those Al Gore depths in the sore-loss stakes. He honestly believed that Obama wasn’t qualified to be president (which wars did Barack fight in?) and that he thought the voters would see that lack of qualification and elect him, McCain, because of it. He seems to have taken deeply personal offense at the loss, and it has weakened him to the point where Hayworth, a Tea Party caricature whom Palin cannot bring herself to support, has forced McCain to spend $20 million to defend his Senate seat. Insecurity is a very expensive vice.

If we were inclined to be sympathetic to McCain, we’d probably say that his problems with conservatives have always been unfairly chronicled. He has always been more of a maverick by auto-conceit than by political record. He’s differed from many in the GOP on immigration, the environment, and campaign finance. But beyond that, he’s a foreign-policy hawk and a deficit-minded tax-cutter. I don’t think he cares much about the social issues. It must be strange for him—bizarre, even—that after a lifetime as a legitimately Republican senator, he has to prove his right-wing bona fides to upstarts from the Tea Party. And I don’t think he knows how to go about it. One is almost inclined to feel sorry for him.