Marketing genius: Picasso at his villa in the South of France in 1957

A new tribe of hyper-rich global nomads is distorting the international property market. Like Hans Holbein’s anamorphosis, it can only be understood when seen from an acute angle. In this case the angle of arrogant wealth. It is not unusual to find an apartment in London or New York being sold for 50 million to someone who has three or four similar homes elsewhere. The currency is neither here nor there since once you are into eight figures, realism gives way to fantasy.

For this tribe art is the ultimate luxury product. Why? Because they make so little of it. Any merely rich person can buy a yacht or a plane, but a Kiefer, Hirst or Cézanne establishes the consumer in an altogether different category of high-net-worthiness. Art is rare and deliciously expensive. What better to excite appetites jaded by jacuzzis and mere Rolls-Royces? Forget about affordable art. The whole point of art as luxury is that it must be unaffordable to all but tiny caste. Limited supply and desperate demand do one thing to prices. People wonder when the billion-dollar work of art will be with us.

Of course, art has always gone where the money is. You once had the Church and now you have hedgies and central Asian gas entrepreneurs. Art as merchandise is not a new idea. Michael Baxendall’s Painting and Experience in Fifteenth Century Italy, 1972, was a helpful revision of a settled academic view of art as a subject for religious or aesthetic speculation alone: he showed that paintings were often competitively traded status symbols. Later, secular art became the first international luxury product.

Banks love art. There were, of course, the Medicis. In the 1960s, David Rockefeller built-up the Chase Manhattan collection. He said it was an exercise in corporate identity, which is to say dignifying usury with painting and sculpture, but it was also a shrewd investment. UBS helped establish Art Basel Miami Beach and Frieze is none-too-subtly supported by Deutsche Bank. The international caravanserai of art fairs might have been designed to support and excite the banking system.

In this hothouse laboratory of taste, art has leapt the species barrier. Its value is no longer, if it ever was, determined by scholars, curators, connoisseurs and critics. Instead, now that it has become a luxury product, its value is established by exactly the same commercial branding methods you would use to sell a premium handbag or wristwatch.

Any visitor to, say, Art HK (soon to be Art Basel Hong Kong) knows this. In a dreadful, pitilessly-lit cavernous space on the Wan Chai waterfront, where prostitutes once strolled (but are now indoors), merchants set up their stalls. It is trade fair of spectacular vulgarity and a chilling rebuke to anyone still nurturing a belief that art has something to do with the fine ideas and responses which Bernard Berenson and Geoffrey Scott discussed at I Tatti. The art is displayed in exactly the same way that diamonds are displayed in the lobby vitrines of The Peninsula Hotel.

The mood is not genteel. A disgraced New York dealer delicately explained: “Being with Rembrandt is like making love. And being with Warhol is like fucking.” In this culture, Jeff Koons is worth more than El Greco, Jasper Johns more than Duccio. But this is also a culture that flies in its water for sushi rice from Tokyo. This is a culture where Larry Gagosian took over a whole airport the better to facilitate the travel arrangements of ravenous clients encumbered by the problem of parking private jets.

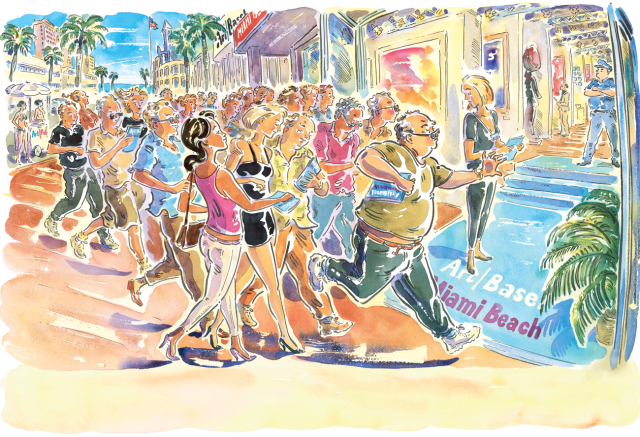

Tom Wolfe has caught this mood in his latest novel, Back to Blood, set in the roiling cauldron of Florida. Already a satirist of the absurdities of conceptualism (whose Painted Word [1975] remains irrefutably mischievous), Wolfe has a demonic eye for the frailties of humanity as revealed in competitive consumption of goods and services. At Art Basel Miami Beach he describes the unusual sight of billionaires in shorts breaking into desperate, covetous runs to access the stalls of dealers selling luxury art.

Fools Rush In

In an excerpt from his new novel, Back to Blood, Tom Wolfe sees Art Basel Miami Beach through the eyes of Magdalena, a young Cuban-American exile, as she watches a local tycoon and a Russian oligarch lock horns over erotic conceptual art—price tag be damned.

It is not so very dissimilar to the January sales. In this venal scrum, successful contemporary artists are brands: value depends not so much (and possibly not at all) on aesthetic merit, but on a profile sculpted by media manipulation. Demand and therefore price are directly related to volume of celebrity. As a business, selling paintings is essentially the same as selling exclusive handbags, but for the brassy plutocrats who collect luxury art, reassuringly more expensive.

The idea of an artist as a brand was Picasso’s, as Bernd Kreutz explained in Die Kunst der Marke (2003). His methodology remains impressive. At some level he realised that merely being a prodigiously talented painter was not enough. At first, it was his art that fascinated the public, but later his wealth (his brand value) became the fascinator itself. Cleverly, he dumped his given-name of Pablo Diego José Francisco de Paula Juan Nepomuceno María de los Remedios Cipriano de la Santísima Trinidad Ruiz y Picasso. He became simply “Picasso”, a brilliant bit of brand management.

He wanted originally to become a painter, but decided on a higher ambition: to become no less than “Picasso”. But, as John Berger explained in Success and Failure of Picasso (1965), Picasso controlled the relationship between production and distribution. “The works,” Berger said “would have to be sold tactfully, so as not to flood the market”. This is what the handbag market calls a premium product strategy. Hermès does the same.

Again, Picasso realised that Malaga, his home town, was not a big enough marketplace, so decided to exploit the cupidity of the new collectors then jostling for primacy in Paris, as they are now in New York, London, Shenzhen, Mumbai and Moscow. For these collectors, 50 years before Detroit established “the annual model change” and brought must-have meretricious novelty to US car buyers every autumn, so Picasso excited demand with a continuous stream of new styles. Collectors dutifully moved on from Blue Period to Cubism, just as consumers would later move on from a ‘57 Chevy Bel Air to a ‘58 Chevy Impala.

Crucially, Picasso understood the media and the value of social networking. The dealer Ambrose Vollard and the writer Gertrude Stein were given freebies, which created firm bonds of loyalty. Picasso would only allow the best photographers of the day—Robert Doisneau, Irving Penn and Man Ray—to take his picture. And Guernica (1937) became the most famous 20th century painting, although there are many rivals for the title of best 20th-century painting, because of adroit and self-conscious media manipulation by its maker.

This then was the beginning of contemporary art as premium-priced luxury product. And in this sense, Damien Hirst is the true inheritor of Picasso. Less flatteringly, but just as apposite, Hirst sold £111m of work at Sotheby’s in the very week Lehman Brothers went bust in 2008. The fallout is still with us, meanwhile newer markets are driving the demand for luxury art.

Art Of Damien Hirst

Yet in the handbag trade, there is evidence that these same markets are becoming fatigued with famous luxury labels. Will Asians tire of Western art soon after they tire of expensive French handbags? Celebrity, as John Updike knew, is a mask that eats the face. In China, consumers in the major cities may have seen enough of LVMH and its wares. There is speculation that, to maintain volumes, Louis Vuitton will have to start building stores in Chinese cities you have never heard of. Will we find Gagosian in Mongolia one day?

Art Of Giacometti

But for the meanwhile, art is the ultimate luxury product: apparently recession-proof, it is rare and richly truffled with status. Any fool can buy a Learjet 60XR for $13m but it takes real financial pistonnage to acquire a Giacometti. Coco Chanel said luxury is not the opposite of poverty, it is the opposite of vulgarity. Alas, that witty definition does not apply to the luxury art market.

Stephen Bayley is an author, broadcaster and critic.