“I call it a sexual revolution: a Catalan boy meets a Flemish girl, they fall in love, get married — and they become European, just like their children.”

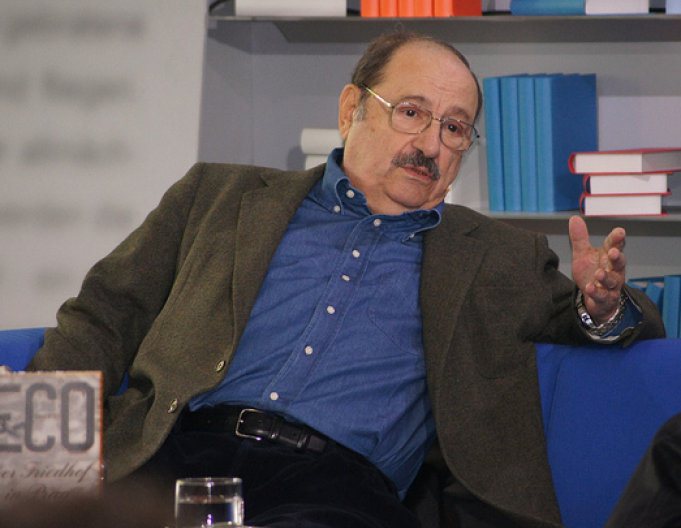

UMBERTO ECO

Umberto Eco has just returned to his office in Milan after a visit to Paris, where French President Nicolas Sarkozy assigned him the title of “Commandeur,” the third rank of the Legion of Honor.

Eco is moved by such tributes to his work, as well as by the recent birthday wishes that arrived from the German President Christian Wolff and Spanish Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy. “By now, we are European by culture, after so many years that Europe was defined by its fratricidal wars,” he says.

Father of semiology, scholar of mass culture, author of essays for the elite and global bestsellers from The Name of the Rose to The Prague Cemetery, Eco has just turned 80. Whenever he gets tired climbing a flight of stairs, he jokes: “Ah, my friend, we’re not 70 anymore!”

From Eco’s office window, the Sforzesco castle looms, with its towers and black birds, a threatening reminder of the many wars that have swept over the continent, Italy and the city of Milan. More than two centuries after its invasion by Napoleon, the area is now overrun with tourists, who come to visit Michelangelo’s La Pietà Rondanini.

“In the face of the debt crisis – and I speak as someone who doesn’t understand anything about the economy – we must remember that it is culture, not war, that forges our identity,” says Eco. “For centuries, the French, the Italians, the Germans, the Spanish and the English have been busy killing each other. We’ve now been at peace for nearly 70 years and no one takes stock in this masterpiece. To even think of a war between Spain and France, or Italy and Germany, is laughable. The United States needed a Civil War to truly unite. I hope that culture and an open market will do the trick for us.”

In praise of Erasmus

Eco sips his coffee, which happens to come from the post-modern formula of a Nespresso capsule. The writer’s German wife, Renate Ramge Eco, stands by the traditional Italian moka recipe.

Eco says that today’s European identity is widespread but “shallow,” using the English word. “That is not the same as the Italian word superficiale, but instead is somewhere between surface and deep. But now we must plant it deeper before the crisis ruins everything.”

Eco mentions Erasmus, Europe’s university exchange program, which is rarely mentioned in the business sections of newspapers. “But Erasmus has created the first generation of young Europeans,” he says. “I call it a sexual revolution: a Catalan boy meets a Flemish girl, they fall in love, get married — and they become European, just like their children.”

“The Erasmus idea should be compulsory,” Eco continues, “not just for students, but also for taxi drivers, plumbers and others. Spending time in other countries within the European Union is the way to integrate.”

The idea is indeed seductive; and yet from newspapers and political parties across Europe, pride looks to be giving way to populism, with E.U. members growing increasingly hostile toward each other.

“That’s why I said that our identity is shallow,” he says. “Europe’s founding fathers– Adenauer, De Gasperi, Monnet – may have traveled less. De Gasperi spoke German, but only because he was born within the Austro-Hungarian empire, and he didn’t have the Internet to read the foreign press. Their Europe reacted to war and shared their resources to build peace. Today, we must work towards building a deeper identity.”

Eco is serious about his proposal for a version of Erasmus for craftsmen and professionals. “When I proposed it at a meeting of E.U. mayors, a Welsh mayor said: ‘My citizens would never accept this!’”

Eco also brought it up recently during an appearance on British television. He says the show’s host shot it down with concerns about the euro crisis, and said the unelected “technical” governments of Papademos in Greece and Monti in Italy were “undemocratic.”

“How should I have responded? By saying that (Italy’s) executive is approved by Parliament and proposed by a president of the Republic elected by Parliament? By saying that all democracies have unelected institutions, like the Queen of England, and the U.S. Supreme Court, and that no one defines them as non-democratic?”

“Just cold landscapes”

Europe’s weak identity, as diagnosed by Eco, was apparent even before the debt crisis. It was evident, he says, “when the E.U. Constitution was rejected by referendum. It was a document that had been written by politicians, and was impossible for any man of culture to participate, and was never discussed with voters.”

Eco also notes how euro banknotes were designed without using the faces of important men and women, another sign of the shallowness of European identity. “Instead, there were just cold landscapes, as in a De Chirico painting. Or does the problem go back to God? The fact that the United States grows more and more religious, as Europe is ever less religious?”

He recalls the debate when Pope John Paul II was still alive about whether the European Constitution should refer to the continent’s Christian roots. “Secular people prevailed and the Church protested. But there was a third way, more difficult, but one that would have given us strength today: To speak in the Constitution of all our roots – the Greek-Roman, the Judaic and the Christian. From our past, we have both Venus and the crucifix, the Bible and Nordic mythology, which we recall with Christmas trees and by celebrating St. Lucy, St. Nicolas and Santa Claus,” says Eco. “Europe is a continent that was able to fuse together many identities, without mixing them up. That is precisely how I see its future.”

Eco cautions about the religious question. “Many of those who say they are non-practicing still carry around a little saint card with a picture of Padre Pio in their wallets!”

The Italian writer, however, is no pessimist: “With all of its defects, the global market makes war less likely, even between the United States and China,” he says. “Europe will never be the United States of Europe, a single country with a common language. We have too many languages and cultures. But on the Internet, in the meantime, we wind up bumping into one another: we may not read Russian, but we see Russian websites and we are made aware.”

“I continue to remember that Lisbon to Warsaw is the same distance as San Francisco to New York,” he adds. “We will remain a federation, but indissoluble.”

So whose faces should we print on our banknotes? Who can remind the world that we are not merely Europeans in a ‘shallow’ way, but that it is something more profound? “Maybe not politicians or the leaders who have divided us, but men of culture who have united us, from Dante to Shakespeare, from Balzac to Rossellini.”