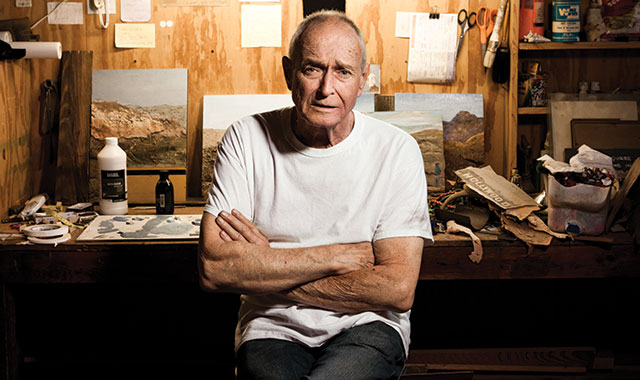

Llyn Foulkes in Studio

Llyn Foulkes in Studio

On July 16, 2012, a painting by a little-known artist sold at Christie’s for $74,500, nearly ten times its high estimate of $8,000. The work that yielded this unexpected result — an acrylic teal-hued painting of a rocky coast called “Nob Hill” — was not the work of a 20-something artist finishing up his MFA. It was a painting created in 1965, and the artist, Llyn Foulkes, is 77 years old and has been working in relative obscurity in Los Angeles for the past 50 years. In March, the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles mounted a retrospective of his work, which will travel to the New Museum in June, marking the first time Foulkes will have had a retrospective at a New York museum.

What’s surprising about this turn of events is not just that it happened but that it’s part of a new pattern, one that defies what everyone thinks they know about today’s art collectors: that they like their artists either very established or — increasingly — young and ultra-trendy. “You have these young hot artists and you have the blue chip work,” said Mitchell Algus of Algus Greenspon, summing things up. “Why would someone buy a Jacob Kassay painting and not a Donald Judd drawing — assuming they’re of equal value? The Judd drawing is great, but it doesn’t carry the social clout that the Kassay painting would carry.”

Such a bias towards mercurial emerging artists has certainly been the rule. But things seem to be changing. Foulkes is among many mid-career artists who are over the age of 60 experiencing the kind of long-overdue career breakthrough in the art world that eluded them in their youth. Mary Corse, De Wain Valentine, Sturtevant, and Judith Bernstein are a few others who are beneficiaries of recent and seemingly growing attention to artists who were active decades ago and who have found their concerns and aesthetics taken up once more by interested dealers, critics, and collectors.

This rising interest in comeback artists might at first seem to dovetail with the recent wave of historical shows that have been mounted at important galleries both large and small, from Algus Greenspon and Marianne Boesky to Gagosian and David Zwirner (the last of which just opened a new wing primarily for historical exhibitions). Last year, Pace and Boesky — two seeming competitors — even came together to present a joint show of work by then 69-year-old Arte Povera artist Pier Paolo Calzolari, marking the artist’s first show in New York in 20 years.

Rediscovered artists often find their early work being reconsidered. Judith Bernstein’s show at the New Museum last year presented both historical drawings and paintings from the start of her career — like her menacing black-and-white drawings of phallic screws — alongside new work, including bright and splashy paintings like “Birth of the Universe #4” which depicts two comic, vaginal-looking creatures with sharp teeth.

Still, the new interest in older artists isn’t just about scholarly rediscovery. The interest has less to do with the necessity of unearthing historical material to understand an artist’s career arc and more to do with feeding an insatiable market. “Unlike the past model where most galleries hosted one new exhibition every four to six weeks, many galleries now have two or more new exhibitions every turn-over,” said Todd Levin, and art advisor and director of Levin Art Group. “There’s a increasing need to fill the constantly expanding number of exhibition opportunities.”

Today, there are some 300 to 400 galleries in New York compared with the roughly 70 galleries in New York in 1970. As for the number of shows galleries mount each year, that has likewise increased: Gagosian mounted 63 last year at its galleries worldwide, David Zwirner had 14 shows at its spaces in New York and London, and Pace had 36 across its three galleries in New York, Beijing, and London. In response to their hydra-headed growth, these galleries have started departing from their original focus. “It’s like mining for gold,” said Levin. “The main veins of ore eventually become depleted, so one starts digging further afield to keep feeding demand.”

Judith Bernstein’s rediscovery is an illuminating story on how that consensus is formed. She was still relatively unknown when she showed at Mitchell Algus Gallery in 2008. It was artist Paul McCarthy’s interest in Bernstein’s work that was the catalyst for her recent revival. When McCarthy saw her show at Algus, he remembered her screw drawings from the ‘60s. He called up his daughter Mara, the owner of The Box, who met with Bernstein, loved her work and gave her a solo show at her L.A. gallery. At that show, mega-gallery Hauser & Wirth scooped up some of Bernstein’s original paintings and drawings. While her drawings can now be picked up for $14,000 to $40,000 a pop — depending on whether you opt for a historical or contemporary work — that may change soon, as there’s speculation that Bernstein may be next in line for joining the blue chip gallery.

Rediscovered artists offer collectors a new pool of work to fuel sales, and one that’s less risky than the still-untested corpus of a younger artist with less material and experience under his belt. “Collecting mid-career and established artists over emerging is not so much a ‘dis’ to the younger generation,” said art advisor Liz Parks via email. According to Parks, recently there has been a sense, conscious or unconscious, of not wanting to participate in the mania over very young and untested artists. “I think collectors want to see the proof in the pudding first.”

Wanting “proof in the pudding” may be a result of the dramatic market shake-up of 2008-9, when artists were madly switching galleries and many galleries were cutting artists, mostly younger ones. “For many young artists, the more ferocious the initial market frenzy for their work, the harder the inevitable crash after early speculative buyers get their fill,” said Levin. And while younger artists are more likely to crash and burn, “the market for rediscovered and re-appreciated mid/late-career artists is usually established in a more gradual and experienced manner, and is less likely to viciously retract.”

No one can deny that the mania for youthful work persists, given the thrill of discovering an unknown artist, investing in him or her, and watching the artist’s market soar overnight. This is well in evidence in the recent case of the 28-year-old artist Jacob Kassay, whose silver deposit and acrylic on canvas works saw a ten-fold leap in their market value at one heady auction in 2010 and then continued to rise over the course of several auctions in rapid succession, turning heads all over town.

Indeed, some collectors still want only that kind of thrill. “We had a collector come in and ask about an artist we were showing,” said one art dealer who asked to remain anonymous. When the dealer told him the artist was close to 40, and had taken some time off before getting her MFA, the collector lost interest. “He thought she couldn’t be a true artist if she was starting so late in life.”

But increasingly, in seems, rediscovered artists do offer collectors the kind of thrill — and opportunity — usually associated with the emerging. Not having had their breakout moment, they are fertile territory for something akin to discovery. On the eve of Llyn Foulkes’s show at Andrea Rosen in 2011, collector Adam Lindemann Tweeted out: “Foulkes Me Twice: Andrea Rosen Gallery and Kent Fine Art Throw Up Shows of Relatively Unknown 76 Year-Old Surrealist Llyn Foulkes.”

For older artists making their comeback today, the challenges of stardom remain, though they have their own dynamics. “One has to make a decision whether one wants to be a comet or a star,” said Levin. “A comet blazes brightly as it quickly flies across the heavens — but it then burns out and disappears. A star’s light is softer than that of the comet, but it twinkles forever. It’s extremely rare for an older artist’s market and career to behave like a comet. The question is — can they solidify into a star?”

For Foulkes, Bernstein, and many others, it seems like it might be their time to sparkle.