The 21st century will not be dominated by America or China, Brazil or India, but by the city. In an age that appears increasingly unmanageable, cities rather than states are becoming the islands of governance on which the future world order will be built. This new world is not — and will not be — one global village, so much as a network of different ones.

Time, technology, and population growth have massively accelerated the advent of this new urbanized era. Already, more than half the world lives in cities, and the percentage is growing rapidly. But just 100 cities account for 30 percent of the world’s economy, and almost all its innovation. Many are world capitals that have evolved and adapted through centuries of dominance: London, New York, Paris. New York City’s economy alone is larger than 46 of sub-Saharan Africa’s economies combined. Hong Kong receives more tourists annually than all of India. These cities are the engines of globalization, and their enduring vibrancy lies in money, knowledge, and stability. They are today’s true Global Cities.

At the same time, a new category of megacities is emerging around the world, dwarfing anything that has come before. A massive influx of people has not only spurred the growth of existing cities, but created new ones virtually from scratch on a scale not previously imagined, from the factory towns in China’s Guangdong province to the artificial “knowledge cities” rising in the Arabian desert. The defining feature of this new urban age will be megalopolises whose populations are measured in the tens of millions, with jagged skylines that stretch as far as the eye can see.

Many will pose challenges to the countries that give birth to them. For though no nation can succeed without at least one thriving urban anchor — and even then, a functioning Kabul or Sarajevo is still no guarantee of national survival — it’s also true that globalization allows major cities to pull away from their home states, a reality captured by the massive and potentially dangerous wealth gap between city and countryside in second-world countries such as Brazil, China, India, and Turkey.

Neither 19th-century balance-of-power politics nor 20th-century power blocs are useful in understanding this new world. Instead, we have to look back nearly a thousand years, to the medieval age in which cities such as Cairo and Hangzhou were the centers of global gravity, expanding their influence confidently outward in a borderless world. When Marco Polo set forth from Venice along the emergent Silk Road, he extolled the virtues not of empires, but of the cities that made them great. He admired the vineyards of Kashgar and the material abundance of Xi’an, and even foretold — correctly — that no one would believe his account of Chengdu’s merchant wealth. It’s worth remembering that only in Europe were the Middle Ages dark — they were the apogee of Arab, Muslim, and Chinese glory.

Now as then, cities are the real magnets of economies, the innovators of politics, and, increasingly, the drivers of diplomacy. Those that aren’t capitals act like they are. Foreign policy seems to take place even among cities within the same country, whether it’s New York and Washington feuding over financial regulation or Dubai and Abu Dhabi vying for leadership of the United Arab Emirates. This new world of cities won’t obey the same rules as the old compact of nations; they will write their own opportunistic codes of conduct, animated by the need for efficiency, connectivity, and security above all else.

Western cities have dominated the ranks of leading urban centers since the Industrial Revolution, a testament to their educated workforces, strong legal systems, risk-taking entrepreneurs, and leading financial markets. New York and London together still represent 40 percent of global market capitalization. But look at the economic map today, and a major shift becomes apparent. Asia-Pacific financial hubs such as Hong Kong, Seoul, Shanghai, Sydney, and Tokyo are leveraging globalization to spur an accelerating Asianization. Money floods into these capitals from around the world but tends to stay within Asia. An Asian monetary fund now provides stability for the region’s currencies, and trade within the Asian sphere has grown much larger than trade across the Pacific. Instead of long-haul flights, the story here is of low-cost carriers connecting planeloads of travelers from Ulan Bator to Kuala Lumpur to Melbourne.

Accelerating this shift toward new regional centers of gravity are port cities and entrepôts such as Dubai, the Venices of the 21st century: “free zones” where products are efficiently re-exported without the hassles of government red tape. Dubai’s recent real-estate overreach notwithstanding, emerging city-states along the Persian Gulf are investing at breakneck speed in efficient downtown business districts, offering fast service and tax incentives to relocate. Look for them to use sovereign wealth funds to acquire the latest technology from the West, buy up tracts of agricultural land in Africa to grow their food, and protect their investments through private armies and intelligence.

Alliances of these agile cities are already forming, reminiscent of that trading and military powerhouse of the late Middle Ages, the Hanseatic League along the Baltic Sea. Already, Hamburg and Dubai have forged a partnership to boost shipping links and life-sciences research, while Abu Dhabi and Singapore have developed into a new commercial axis. No one is waiting for permission from Washington to make deals. New pairings among global cities follow the markets: Witness the new Doha to Sao Paulo direct flight on Qatar Airways or the Buenos Aires to Johannesburg route on South African Airways. When traffic between New York and Dubai dried up due to the financial crisis, Emirates airlines rerouted its sleek Airbus A380 planes to Toronto, whose banking system survived the economic shake-up in better shape.

For these emerging global hubs, modernization does not equal Westernization. Asia’s rising powers sell the West toys and oil and purchase world-class architecture and engineering in return. Western values like freedom of speech and religion are not part of the bargain.

This is very much the case in the monarchies of the Persian Gulf, where urban ambition is manifest in iconic new districts ordered up in the desert sands. Abu Dhabi is creating the solar-powered, car-free Masdar City — meant to be the world’s first carbon-neutral, no-waste city — and colonizing its Saadiyat Island with architectural marvels to house new Guggenheim and Louvre collections in stunning new buildings by Frank Gehry and Jean Nouvel. The emirate has embraced a two-decade master plan to invest not only in new cities, but in smart ones that will take into account land use, sanitation, efficient transport, and community building, in hopes of making itself into a place where Westerners will flock for a better quality of life (certainly not because of the climate or its starring role in Sex and the City 2). Already the result in the Persian Gulf is something truly new, as a once-barren cultural zone features increasingly global melting pots like the Qatari capital of Doha, where residents hail from more than 150 countries and far outnumber the locals. If these new five-star hubs play it right, they could convince Westerners to give up their citizenship for permanent homes in a friendlier, tax-free environment.

Then there are the megacities, superpopulous urban zones that are worlds unto themselves but that — for now — still punch below their weight class economically: Think Lagos, Manila, or Mexico City. When Tokyo in 1980 became the first metropolitan area to reach a population of 20 million, the figure seemed almost unimaginable. Now we need to get used to the idea of nearly 100 million people clustered around Mumbai or Shanghai. Across India, more than 275 million people are projected to move into the country’s teeming cities over the next two decades, a population nearly equivalent to that of the United States. During a recent trip to Jakarta, a minibus-clogged megalopolis of 24 million, it struck me that many if not most of the residents will never leave their city’s expanding perimeter or know much of the outside world beyond the airplanes flying overhead. In just a few decades, Cairo’s urban development has stretched so far from the city’s core that it now encroaches directly on the pyramids 14 miles away, making them and the Sphinx commensurately less exotic than when my father was photographed there in the 1970s, with just the pyramids and a camel in view.

The millions of urban squatters pouring into megacities each year are not simply a new global migrant underclass, consigned to live in chaos and work in the shadow economy. Instead, they often form functional, self-organizing ecosystems that are “off the grid.” But one result is an echo of the physical stratification of medieval cities; where knights and walls once protected the aristocracy from unwanted outsiders, now electrified gates and private security agencies do the same. Gurgaon, not long ago a sleepy farming village outside New Delhi, has become a high-rise, high-tech satellite of more than half a million people and was recently ranked India’s best city to work in. It offers gated complexes, such as Windsor Court, with their own grocery stores, kindergartens, and social clubs all in one compound so that only working husbands ever have to face the real world of India’s choking traffic and noxious pollution.

Indeed, economic inequality flourishes in these massive new urban clusters. Consider the skylines of Istanbul, Mumbai, and Sao Paulo, where stunning high-rises are surrounded by ungodly scenes of destitution and squalor. Indian billionaire Mukesh Ambani, the world’s fourth-richest person, is reportedly spending close to $2 billion on the construction of his 27-story home — complete with hanging gardens, a health center, and helipads — all with a bird’s-eye view of Mumbai’s largest slum, Dharavi. Once, while jogging on a treadmill on the top floor of a Sao Paulo hotel, I tried to count the many helicopters buzzing by. The city has the highest rate of private helicopter use in the world — a literal sign of what heights people will go to in order to avoid the realities of the world below.

Build a better future or are heading toward a dystopian nightmare.

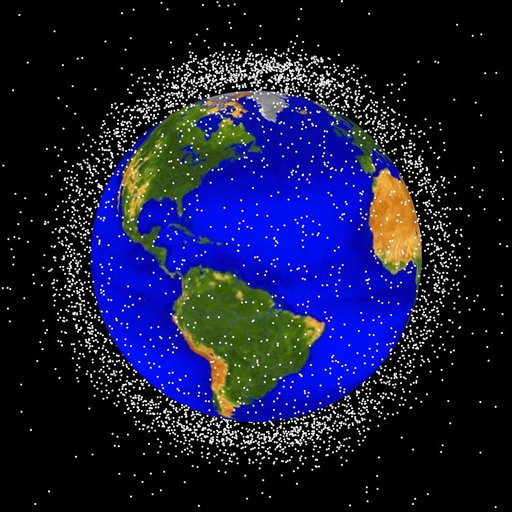

Taken together, the advent of global hubs and megacities forces us to rethink whether state sovereignty or economic might is the next age. Look at a satellite image of the Earth at night: It will reveal the shimmering lights of cities flickering below, but also an ominous pattern. Cities are spreading like a cancer on the planet’s body. Zoom in and you can see good cells and bad cells at war for control. In Caracas, gang murders and kidnappings are a fact of life, and al Qaeda terrorists hide in plain sight in Karachi. Film director Shekhar Kapur is working on an epic titled Water Wars: It is set not in parched Africa or the fractious Middle East, but Mumbai. Anyone who traveled to South Africa for the 2010 World Cup might have noticed how private security forces outnumbered official police two to one, and gated communities protected elites from the vast townships where crime is rampant. Cities — not so-called failed states like Afghanistan and Somalia — are the true daily test of whether we can bew prerequisite for participating in global diplomacy. The answer is of course both, but while sovereignty is eroding and shifting, cities are now competing for global influence alongside states.

Columbia University scholar Saskia Sassen has done the most to contribute to our thinking about how urban advantage translates into grand strategy. As she writes in The Global City, such places are uniquely suited to translate their productive power into “the practice of global control.” Her academic work has traced how Europe’s largely autonomous Renaissance cities such as Bruges and Antwerp innovated the legal frameworks that enabled the first transnational stock exchanges, setting the stage for international credit and the forerunners of today’s trading networks. Then as now, nations and empires did not restrain cities; they were merely filters for cities’ global ambitions. The supply chains and capital flows linking global cities today have similarly denationalized international relations. As Sassen argues, in cities we can’t make trite divisions between the government and private sector; either they work together or the city doesn’t work at all. Even massive national investments in telecommunications or other infrastructure don’t equalize the balance of power between cities and the rest; they ultimately reinforce the power of cities to conduct their own “sovereign” diplomacy.

Consider how aggressively Chinese cities have now begun to bypass Beijing as they send delegates en masse to conferences and fairs where they can attract foreign investment. By 2025, China is expected to have 15 supercities with an average population of 25 million (Europe will have none). Many will try to emulate Hong Kong, which though once again a Chinese city rather than a British protectorate, still largely defines itself through its differences with the mainland. What if all China’s supercities start acting that way? Or what if other areas of the country begin to demand the same privileges as Dalian, the northeastern tech center that has become among China’s most liberal enclaves? Will Beijing really run China then? Or will we return to a fuzzier modern version of the “Warring States” period of Chinese history, in which many poles of power competed in ever-shifting alliances?

Think about it: Even today’s most centralized empire-state could be undone by its cities. Gone are the days of Mao when peasant uprisings could collectively capture the nation. Today, controlling the cities, not the countryside, is the key to the Middle Kingdom. The same is very much the case in Africa’s fragile post-colonial nations. Africa’s urbanization rate is approaching China’s, and the continent already has nearly as many cities with a population of 1 million or more as Europe does. But decades of despotism and civil wars haven’t yielded governments that can hold together entire countries — let alone Africa’s two geographically largest nations, Sudan and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Instead, these countries seem to be headed toward division, with the new borders following and surrounding the main cities that are their gravity points, like Juba in South Sudan and Kinshasa in Congo. Or perhaps borders don’t need to change at all, but rather melt away, so long as locals have access to the nearest big city no matter what “country” it is in. This is, after all, how things really work on the ground, even if our maps don’t always reflect this reality.

As our world order comes to be built on cities and their economies rather than nations and their armies, the United Nations becomes even more inadequate as a symbol of universal membership in our global polity. Another model could be built on the much less rigid World Economic Forum of Davos fame, which brings together anyone who’s someone: prime ministers, governors, mayors, CEOs, heads of NGOs, labor union chiefs, prominent academics, and influential celebrities. Each of these players knows better than to rely on some ethereal “system” to provide global stability — they move around obstacles and do what works.

The scope of urban ambition today ranges from new business districts to special economic zones to entirely new cities never before on the map. Sitting down recently at a construction site on the banks of the Elbe River, I spoke with Jürgen Bruns-Berentelg, CEO of Hamburg’s bold new HafenCity project. A veteran of Berlin’s futuristically redesigned Potsdamer Platz, he has resuscitated Hamburg’s neglected industrial waterfront and turned it into an efficient, job- and family-friendly island, seamlessly integrated into this revitalized German city. “We’ve moved from arbitrary to curated urban design,” he told me confidently. Just as Hamburg was once a powerful trading linchpin of the medieval Hanseatic League because of its proximity to the Baltic Sea, HafenCity’s ample new port terminals look to capitalize on changing trade patterns to capture a larger slice of the massive global shipping market. But HafenCity is also designed to house 21st-century industries. Global companies such as Procter & Gamble have moved their regional headquarters into buildings that are so ecoefficient that their toilets don’t use water. “For both businesses and residents,” Bruns-Berentelg pointed out, “moving to HafenCity is more than a rental decision — it’s a lifestyle choice.” Officials from Rotterdam, Toronto, and other forward-thinking cities are coming to learn from HafenCity, whose residents are in a way the pioneers of urban renewal for the Western world, which doesn’t have the luxury of building cities from scratch.

Africa, however, does — and that’s precisely what Stanford University economist Paul Romer is pushing. His “Charter Cities” initiative aims to help poor countries leapfrog into the urban age by embracing an idea much like charter schools: Set aside a plot of land, give it special administrative status and flexibility (as China did in leasing Hong Kong to Britain), and then step out of the way and let experts run it. Romer is in discussions with countries in Africa to find a candidate willing to provide the land for a pilot project; his plan has the potential to transform an entire country’s fortunes. Whether or not his utopian and, to some, neocolonial dream goes anywhere, some places have already successfully experimented on their own: China’s Guangdong province has had special economic zones for decades, meant to cut out hidebound bureaucracies in favor of business-friendly parastatal governance. Enclaves from King Abdullah Economic City in Saudi Arabia to Binh Duong in Vietnam are now copying the model.

Charter cities are a poor man’s version of South Korea’s $40 billion Songdo project, which promises to stand in a class of its own upon completion in 2015. Touted as the most expensive private development in history, Songdo is more than a new business district or economic zone; it will be the world’s first sentient city, using advanced communications technologies to make life seamlessly interactive, from homes to schools to hospitals. Each wave of new residential and commercial blocks that comes on the market sells out almost instantly in connectivity-crazed South Korea. It also represents Asia’s chance to turn its demographic concentration and burgeoning consumption from a threat to the planet into a model that can be re-exported to the developing world. The estimated 300 new cities that China alone has planned are a huge market opportunity for green developers like Gale International, which leads the Songdo project, to deploy ecofriendly city plans.

Indeed, Songdo might well be the most prominent signal that we can — and perhaps must — alter the design of life. Cities are where we are most actively experimenting with efforts to save the planet from ourselves. Former U.S. President Bill Clinton has brought together mayors from 40 large cities to build a network of best practices for reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Vertical farming, long in vogue in Tokyo, is spreading to New York; the electric mass-transit system of Curitiba in Brazil is being copied in North America; Cisco is embedding sensors in Madrid’s traffic signals to make the city traffic-free. The consulting firm McKinsey recently estimated that if India pursues urbanization in an ecoefficient manner, it will not only make the country a healthier place, but add an estimated 1 to 1.5 percentage points to its GDP growth rate.

In this way, a world of cities can spark a cycle of virtuous competition. As geographer Jared Diamond has explained, Europe’s centuries of fragmentation meant that its many cities competed to gain an edge in innovation — and today they share those advances, making Europe the most technologically developed transnational zone on the planet.

What happens in our cities, simply put, matters more than what happens anywhere else. Cities are the world’s experimental laboratories and thus a metaphor for an uncertain age. They are both the cancer and the foundation of our networked world, both virus and antibody. From climate change to poverty and inequality, cities are the problem — and the solution. Getting cities right might mean the difference between a bright future filled with HafenCitys and Songdos — and a world that looks more like the darkest corners of Karachi and Mumbai.