David Cameron faces toughest hand of cards ever dealt a new prime minister

The Conservative party leader has no majority and an uncertain ally. He is not on top, but on probation

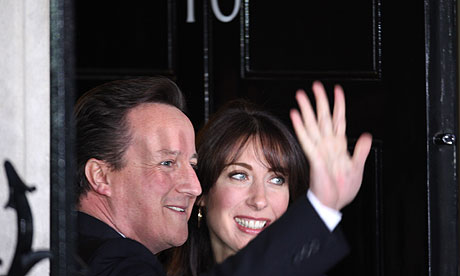

David Cameron at No 10 Downing Street. Photograph: David Levene for the Guardian

David Cameron at No 10 Downing Street. Photograph: David Levene for the Guardian

David Cameron‘s arrival in Downing Street at 8.45pm tonight saw no air-punching triumph. It was more like a marathon runner collapsing over the finishing line. But he had reached his goal. He spoke his homily with dignity. The door banged shut. The chaos and the discord of recent days receded and the adrenalin of power will have seeped into his veins. Cameron faces the toughest hand of cards ever dealt a new prime minister but he has orchestrated the game brilliantly so far. The first peacetime coalition since the 1930s has emerged fully formed from the electoral wreckage of the last four days. It at least hints at a political realignment on the centre-right, similar to that seen in English local government for the past five years (largely unnoticed at Westminster). Without it, Cameron clearly felt he could not undertake the engineering of a massive restructuring of public finances. He may be famously unflappable. He may have a sense of humour, a capacity to listen and social assurance, but he faces the labours of Hercules. He has passed the first test.

The Tory leader has conducted the five days since the election with dignity and some panache. On Friday afternoon, when he was exhausted, he arrived at his first press conference at the St Stephen’s Club cool and well briefed. A statesmanlike proposal for a “new and comprehensive” coalition with the Liberal Democrats was so well crafted as to seem premeditated. It took time to sink in, but it worked.

Cameron knew that Nick Clegg had to be made instantly comfortable. Whichever big party the Lib Dems chose to support, Clegg’s moment of power and glory would not last. Torn this way and that by his notoriously decision-averse backbenchers, he would dally and dither, but he had to feel personally at ease with Cameron, and he was unlikely to feel at ease with Gordon Brown.

On Monday evening Cameron carried his MPs with him to an extent that surprised observers. He had made the Lib Dems a fair offer and could do no more. It was up to them. The question was the same as faces a third party in any hung parliament: with whom would they stand the least chance of committing suicide? The Lib Dems chose the Tories.

The last time a new government faced a comparable economic crisis, under Margaret Thatcher in 1979, she enjoyed a parliamentary majority and an opposition in disarray. Cameron has no majority and, on past evidence, an uncertain ally. Thatcher’s budgets of 1979-81 proved so unpopular it took victory in the Falklands war to rescue her.

Cameron has a war but with no hope of victory. He must seem a responsible custodian of the nation’s economy through a transitional parliament, with probably less than a year in which to establish himself. Coalition is the weapon with which he has chosen to do so.

Cameron’s rise to power was famously effortless. Eton and Oxford – complete with embarrassing photographs – were followed by an apprenticeship in media public relations with which few voters could identify. He was then eased into the political purple under Norman Lamont and Michael Howard. With all this against him, one of his most successful campaigns has been to cleanse the image of his past.

A young family and a bicycling habit, a directness of speech and a careful distancing of his lifestyle from traditional Toryism played well. Cameron may look like a toff, but he never walks or talks like one. His defining “set”, that of media-friendly Notting Hill, was initially a presentational asset, even exploited as the new Tory Camelot.

His error was in becoming trapped by that asset, appearing the prisoner of a cabal of the close friends with whom he had long surrounded himself. Notting Hill served him well when it was merely the subject of envy. When things went less swimmingly, as under the “Brown bounce” of 2007, Notting Hill looked cosy and elitist. Seen from the suburbs and the shires, “the Cameroons” were reminiscent of the Tony Blair luvvies, cuckoos in their party nest, smart, metropolitan, faintly metrosexual and not completely trusted.

As Blair relied on his clique to the exclusion of his party, so Cameron seemed to turn his back on the Tory apparatus, local and national. There seemed no room for the old guard who once ran the Conservative national union, its central office and shadow cabinet. This semi-detached general staff had served such leaders as Macmillan, Douglas-Home and Heath. Thatcher and her successors tore it apart.

As the election headed for a hung parliament, Cameron’s court seemed ever more out of touch. His personal bonding with George Osborne was its key relationship, like Blair’s with Brown. Osborne was so identified with Cameron that he must be the only man accused of going to Eton when he never did. Nor, for that matter, did others in the court such as Steve Hilton, Andy Coulson and Michael Gove.

Cameron’s bond with Osborne meant he rejected private advice to reshuffle him in 2009, when the Tories were conspicuously failing to land blows on Brown’s handling of the economy and were being outgunned by the Lib Dems’ Vince Cable. Cameron compounded the mistake by putting his friend in charge of election strategy. This meant any mistakes would weaken Osborne as a future chancellor. There were plenty, including the choice of the wrong European party to join, support for Lord Ashcroft and the vacuous “big society” theme. It was William Hague, not Osborne, who emerged as Cameron’s spokesman for the negotiating team this past four days.

All this has been mere apprenticeship. On Monday and yesterday, Cameron took the message of his partial failure and scrupulously communed with his new MPs in the parliamentary anterooms. He consulted the older guard who have long whispered against his inexperience and lack of rapport with the grassroots. He fell back on his charm, his ability to command a room and, as was once said of him, “to make every crisis seem reasonable”. He sold a Tory-led coalition.

In fairer times Cameron’s qualities should make him a competent coalition prime minister. Like many Conservative leaders, he travels ideology-lite, with pragmatism bred in the bone. When he has drifted into ideology – on the big society and responsible citizenship – he has sounded wooden and waffly. When he has advocated a specific policy, as on Afghanistan or “efficiency savings”, he has been plodding. But when glad-handing his way across the political spectrum, he is all things to all men. Indeed to some, his one-time (private) reference to himself as “the heir to Blair” has seemed too close for comfort.

Despite the noises required of him during the campaign by the party back-woods on defence, immigration and crime, Cameron is far from the Thatcherite demon beloved of the Labour tribe. He is comfortable with the liberal climate of British politics, in contrast to his predecessors, Michael Howard and Iain Duncan Smith. He has no trouble with carbon capture, gay rights, civil liberties, cycle lanes and protecting frontline services. He and his circle are emphatically post-Thatcherite. Were most of them not forced to pitch their tents in Tory shires, they would probably liberalise the drug laws, cut prisons, punish bonuses and even be civil to Europeans. Now allied to the Liberal Democrats and with coalition able to silence the right, strange things may yet occur under Cameron.

The two coalition leaders reportedly got on well during the negotiations. They are much alike in outlook and in public school and Oxbridge background. A deal was almost signed at once, when Clegg was stopped in his tracks by elder statesmen such as Lord Ashdown and Lord Steel and by MPs sticking to the Lib Dem tradition of refusing to decide whom to support in power. As in 1977 and more recently in Wales and Scotland, Liberal Democrats tend to split even before they have come together.

That certainly suggests trouble ahead. A deeper trouble lies within Cameron’s own party. He may think coalition is the great disciplinarian. But over the past quarter century the party has been stripped to its hard core. Gone is the wide church of two to three million members, Young Tories and policy-making groups that underpinned electoral success in the 1950s and 1960s. Thatcher and her successors drove away milder Conservatives who might now see Liberal Democrats as tolerable bedfellows. The party backbone is composed of hard-nosed men and women with whom Cameron regularly crosses swords at constituency meetings, implacable on Europe and immigration, fierce on hunting and crime.

These Conservatives have spent this week rushing to the Tory blogs to demand that Cameron stay in opposition. In their view he should have allowed Brown to drive Labour yet deeper in the mire of illegitimacy. They see opposition as strength, from which to slay the wounded Labour carthorse for good and all at the next election.

For these party members, Cameron is already suspect. He did not win the expected election victory and has consorted “in flagrante” with despised Liberal Democrats. He is not on top, but on probation. He may have presented himself as well-groomed, decent and personable. But many of the party faithful prefer leaders who win elections by eating barbed wire for breakfast.

The new prime minister has a team that is painfully short of executive experience, either inside or outside government, and coalition partners who never even expected high office. They are all new boys and girls. Unless Cameron can perform miracles of leadership, his stay in Downing Street may be one of inner calm but it seems likely to see external turmoil. British politics remains tribal. Liberal Democrat and Tory MPs will slide easily into rebellious conclave, while Labour regroups under a new leader.

Cameron’s talent for seeing reason in every crisis will be sorely tested. For him the election may at last be over, but the next one has just begun.