Over the past decade, Western media have repeatedly portrayed images of Muslim women as victims. We have read about the Taliban publicly beating young

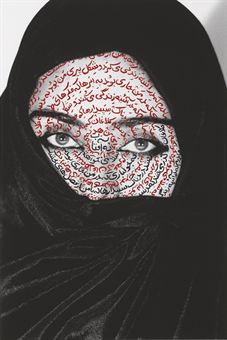

women who laugh in the street; we have read about the targeted killings of professional Iraqi women – doctors, journalists, lawyers – who represent an opposing view to an extremist agenda. Americans have so often seen Muslim women as silent victims that they probably conjure picturesque images of shapeless and silent figures in bright blue burqas as synonymous with “Muslim women.”

Behind the veil

To be sure, they are among the victims. But as the United States works with Afghan locals to develop policy, it must consider this: In order to responsibly promote democracy and support human rights within countries working toward reform, women must be included in making policy decisions.

Women are some of the greatest advocates for progressive, antiextremist agendas and to ignore their solutions would be an unfortunate mistake. If policymakers were able to identify and address the barriers to women’s participation in matters of public discourse, they would soon be able to open a new space for moderate voices.

It’s not as though women haven’t been trying to participate in such dialogue:

The Afghan Women’s Network called on NATO to include Afghan women’s perspectives in provincial reconstruction team activities in Afghanistan back in 2007.

They pointed out that women’s right to physical security and participation was being undermined, if not all together violated, because the reconstruction teams were not specifically taking women into account. International policymakers were missing out on reconstruction opportunity by not providing women the additional protection and resources they needed to travel safely to the provincial-level government meetings. Because their right to physical security was not addressed, they were unable to participate in important decisionmaking bodies and the ideas that they could have brought to the table – thoughtful suggestions on how to fight extremism based on their own experiences – was lost.

A hallmark of women’s groups, like the Afghan Women’s Network, is that their thinking on the fight against extremism is strategic and long-term. Their recommendations put forward solutions that would strengthen the US and NATO forces on the ground. They have emphasized the inclusion of gender advisers, and strengthened institutional memory in reconstruction teams to create a record of what works and what fails in conflict situation like Afghanistan.

Critics will argue that culture and human rights are two different values in conflict – they will say that a liberated woman is a Western value. Others will say that we need to win the war against extremists first, and then we will address women’s issues. But if the women themselves are working hard to be heard, then that argument falls apart.

More than 200 Muslim women leaders met at the Women’s Islamic Initiative for Spirituality and Equality (WIISE) conference in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, last summer to discuss the underrepresentation of women. WIISE launched the Global Muslim Women’s Shura Council, an all-women’s council that will promote women’s rights within an Islamic framework.

If such work was supported internationally, women could put their effort into solving unrest in the region.

For example, WIISE has begun training Muslim women as jurists who can offer valid legal opinions and interpret religious texts on issues such as women’s equality. By training women who have the authority to provide religious interpretation they are creating a new pool of thought leaders.

When women can offer new interpretations of religious texts such as the Koran, it allows for the emergence of moderate voices and views within Muslim society.

In most cases, giving a public voice to Muslim women’s opinions is giving voice to antiextremist perspectives on Islam. Educating women to be jurists, or supporting their participation in political decisionmaking, would not only act as leaven in societies where their ideas have traditionally been repressed, it would provide the space to help others actively challenge extremism.

If the US really wants to support Afghanistan, it should start by acting as the Afghan Women’s Network suggests and implement the policies and human rights agreements which the US has already signed, such as United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325, throughout US security operations by making women equal players at all levels.

Another way to support that would be to increase the use of US female troops in the already existing Female Engagement Teams (whose mission is to engage with local Afghan women) in Afghanistan and to mobilize them consistently. That type of modeling of respect for women and show of empowerment, would dramatically improve the US ability to build positive relations with both male and female community members, and through that improve US chances at creating a more stable environment in general.

We know that Muslim women’s rights agendas vary from country to country, from conflict zone to repressive regimes. Their problems are not monolithic and require solutions appropriate to their own particular Islamic cultural, political, and social context. Policymakers working on the development and direction of funds in places like Afghanistan should draw on these women’s experience, dedication, and knowledge to increase our combined ability to come up with appropriate, culturally sensitive, and long lasting solutions to combat extremist agendas.