China and America square off in the latest round of recriminations, how bad are relations really?

It is probably the most important relationship of today’s world, and even more of tomorrow’s. If the United States and China cannot co-operate, what hope of stemming climate change and the spread of nuclear weapons, or returning the global economy to a path of stable growth? Over the past decade, the established superpower and the rising one have rubbed along reasonably well; relations with China are, by common consent, one of the few things George Bush junior got mostly right. But under Barack Obama, after a cordial start, slights have been building up for a while. The past week has produced a sharp reminder of how sensitive the relationship can be—and how quickly it might spin out of control.

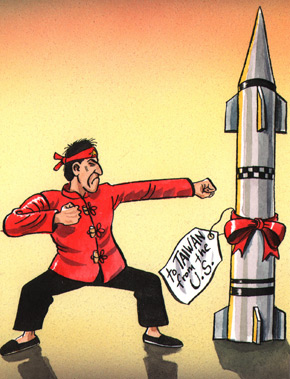

The issue, as so often in the past, was Taiwan, and in particular America’s promise to defend the island republic from the Communist mainland, which continues to claim sovereignty over it. America’s Congress has embodied this commitment in law: the United States is obliged under the Taiwan Relations Act of 1979 to provide the island with the arms it needs to defend itself. On January 29th the Obama administration gave Congress notice of more than $6 billion-worth of arms sales it had determined to be necessary for Taiwan’s defence. These included some sophisticated weaponry, including Harpoon anti-ship missiles and Black Hawk helicopters.

China promptly had a fit. It summoned America’s ambassador and scolded him for this interference in China’s “internal affairs”. It announced that it would cut some of the recently strengthening ties between the armed forces of the two countries. And it threatened to impose commercial sanctions on the American firms whose weapons might be sold to Taiwan, cutting them out of China’s own market. This looks like a highly uncomfortable collision between the two big powers. How worried should the rest of the world be?

To answer that question, it is necessary to look behind the show. China is rather prone to having fits, or at least at seeming to have them. But in fact Chinese officials would not have been in the least surprised by Mr Obama’s decision to sell these weapons to Taiwan. American officials have long insisted, for public consumption at least, that they do not consult China about such sales. Nonetheless James Jones, Mr Obama’s national security adviser, said on the same day as the announcement that America would consult China “in a transparent way” on the issue. Officials later clarified that he had meant notify, rather than consult. But since big elements of the package had been agreed on by Mr Bush (and delayed by political wrangling in Taiwan and haggling between Taiwan and America), China has had plenty of time to brace itself and plan its response.

Though they naturally did not say so, the Chinese were no doubt pleased that Mr Bush’s unfulfilled offer to equip Taiwan with submarines was not taken up by Mr Obama. The package did include 60 Black Hawk helicopters, which Mr Bush had not approved, but these will hardly intimidate China. Taiwan did not get the new F-16 fighter planes it has long requested. The last time America agreed to sell Taiwan F-16s (a less advanced version than Taiwan is now angling for) was in 1992 when the first George Bush was president. That did enrage China, but its reaction then was tempered by a sense of vulnerability after the collapse of communism in Europe. Now, in response to a less threatening list of weapons, it is feeling less restrained.

Even so, its reaction this time has not alarmed the China-watchers in Washington, DC—not so far, at least. A senior administration official said the response had been “pretty much as expected” and consistent with previous episodes. China commonly responds to American arms sales to Taiwan by suspending military dialogue. After the F-16 sale, it also withdrew from UN talks on arms control. But the importance of preserving its relationship with America has always been paramount. China knew when it established diplomatic ties with America in 1979 that arms sales would continue.

In effect it acknowledged this in a joint communiqué issued in 1982 under Ronald Reagan, in which America pledged non-committally “gradually to reduce its sale of arms to Taiwan, leading, over a period of time, to a final resolution.” Both countries promised to make efforts to create conditions “conducive” to this. As officials in America and Taiwan see it, China’s massive deployment of missiles and other offensive weaponry on its coast facing Taiwan since the late 1990s is far from conducive to an end to American arms sales. China’s arms build-up has continued since the inauguration in May 2008 of a more China-friendly president in Taiwan, Ma Ying-jeou, and despite a rapid improvement in cross-strait political ties.

As Chinese officials see it, however, the world has dramatically changed since the early 1990s when the first President Bush sold the F-16s, and again since 2001 when his son first offered Taiwan another huge array of weapons, including the submarines. America’s weaknesses, they feel, have become particularly apparent since the outbreak of the financial crisis in 2007. China, they believe, has continued to grow stronger. The global balance of power, argue many Chinese scholars, is shifting in China’s favour. China can afford to flex more of the muscle amassed by its double-digit annual increase in defence spending over most of the past two decades.

All the same, China is hardly likely now to stage a repeat of the sabre-rattling, including unarmed missile firings close to Taiwan, that brought it perilously close to war with Taiwan and America in the mid-1990s. That crisis was fuelled by what China saw as separatist statements by Taiwan’s president, Lee Teng-hui, including those he uttered on a private visit to America in 1995. China was unnerved too by the approach of Taiwan’s first direct presidential elections in 1996, and wanted to deter voters from supporting Mr Lee or other China-sceptical candidates. The health of Deng Xiaoping, China’s semi-retired elder statesman, was failing and his successor, Jiang Zemin, wanted to prove himself.

China’s relations with Taiwan have thawed massively after a dozen years of frostiness following the standoff. Having seen the strength of American resolve in 1996, with the sending of two aircraft-carrier battle groups close to Taiwan, it is probably not anxious to test it again—even though its own deployment of missiles and submarines could make American carriers more wary.

China’s fit of indignation was largely for show, what was Mr Obama’s motivation in announcing the Taiwan arms sales right now? One school of thought has it that the American president, beset by domestic troubles, decided at last to “push back” against a China that had been insufficiently responsive and on occasions downright hostile to his first-year charm offensive.

The Americans certainly feel they have cause for complaint and concern. The strength of China’s rhetoric over Taiwan suggests that relations are changing in what could prove a worrisome way. In recent months China’s leaders have become more prickly in their dealings with the outside world. Signs of this have included sending a relatively junior official to negotiate with Mr Obama during the climate-change summit in Copenhagen; the sentencing of a prominent dissident to an unusually lengthy jail term in December; the execution that month of a supposedly mentally ill British drug-dealer despite appeals from the British prime minister; China’s more robust position in territorial disputes with its neighbours, and an unwillingness to back sanctions on Iran.

After all that, there is scant evidence that Mr Obama intended to use the Taiwanese weapons sale as a means of showing a tougher face to China. The transfer had to be announced at some time, and this, said a senior official, was “one of those issues where the timing is never right”.

Indeed, one way to read the timing is that it was intended to minimise friction. It would have been far more provocative if America had announced the sale on the eve of Mr Obama’s visit last November or immediately afterwards—just before the Copenhagen summit. With President Hu Jintao expected to visit the United States later this year, this was not a bad time to get unpleasant business out of the way. American officials scoff at the idea that Mr Obama would let some of the “rude” personal behaviour he encountered from some Chinese officials in Copenhagen influence strategic decisions. And if he was in a mood for lashing out at China, why did this not show in the Defence Department’s latest Quadrennial Defence Review, released on February 1st?

Compared with the last such document issued in 2006 under the Bush administration, this one (see article) dwells far less on the danger posed by China’s rise. Four years ago the review said that, among major and emerging powers, China had the “greatest potential to compete militarily” with America. The pace and scope of China’s military build-up, it said, had already put regional military balances “at risk”.

The latest report repeated the last one’s concerns about the secrecy of China’s military build-up. But it also said that China’s developing military capabilities could enable it to play “a more substantial and constructive role in international affairs”. In 2006 the Defence Department noted China’s large investment in cyber-warfare as well as counter-space and missile systems. America, it said, would “seek to ensure that no foreign power can dictate the terms of regional or global security.” This time it stressed the need for China and America to “sustain open channels of communication to discuss disagreements” in order to reduce the risk of conflict.

The internet’s role

All in all, the evidence suggests that neither the American arms package nor China’s reaction to it was intended to disturb a relationship that is often fraught but in which both sides have made a big investment. That said, it would be wrong to suggest that the two countries see eye-to-eye on all or even most big issues, or to rule out a dangerous falling-out in the future. Some dangers seem to be increasing. One big change, says Doug Paal, a senior China adviser to previous American presidents and now at the Carnegie Endowment in Washington, DC, is that the growth of the internet generation in China nowadays requires its government to heed the strong nationalist sentiment of its own people.

Newspapers in China say as much themselves. The Global Times, a Communist Party-linked newspaper in Beijing, argued that China’s “stronger than expected response” to the Taiwan sales was in part a reflection of changing public opinion. In recent years, it said, public sentiment had been “increasingly shaping China’s foreign policy strategies” and driving the Chinese government to respond more strongly to American “provocation”.

That, admittedly, is only one side of popular Chinese attitudes to America. The newspaper did not discuss the enormous attraction that American culture still exerts in China. The Hollywood blockbuster “Avatar” has recently been a colossal hit, provoking much speculation among Chinese about how the authorities might be reacting to its anti-authoritarian overtones. Google’s recent battle with the Chinese authorities has also been widely applauded by people inside China. But the web cuts both ways. The past decade has seen periodic upsurges of anti-Western sentiment, magnified by the freedom internet users enjoy to air such views without interference from the usually heavy hand of China’s online censorship.

That is why there is likely to be both popular and government outrage against Mr Obama later this month if, as many expect, he decides to meet the Dalai Lama during the Tibetan spiritual leader’s visit to America. The White House said this week that the Dalai Lama was “an internationally respected religious and cultural leader” and that, although America considered Tibet a part of China, Mr Obama would meet him in that capacity. China responded that any meeting would “seriously undermine the political foundation of Sino-US relations.” Tibet touches a raw nerve (see article). The riots in Lhasa of March 2008 and subsequent unrest across the Tibetan plateau triggered an anti-Western backlash online and in the media.

Such feelings were tamed by the West’s sympathetic response to an earthquake in Sichuan Province in May 2008 that killed 70,000 people, and by the decision of Western leaders (Mr Bush especially) to attend the Olympic games in Beijing in August that year. But they have not gone away. Chinese officials, though wary of confrontation with America, also fret that popular nationalism could turn against the Communist Party itself if the party is seen as caving in to the West.

This might explain why officials are now threatening to impose trade sanctions on American companies involved in weapons sales in Taiwan (an idea that gained a lot of online support even before the announcement from Washington). China is unlikely to follow this through in more than a token manner. Some of the American firms involved do little or no business there. But Boeing, which makes the Harpoon anti-ship missiles, has also produced more than half of China’s commercial jets and ensures they stay airworthy with spare parts. The Chinese are well aware that Boeing has operations in many American states and that Congress would react strongly if sanctions went ahead.

Still, these are tense and unpredictable times in trade relations between the two countries. On February 1st China’s Ministry of Commerce issued a statement saying that trade protectionism had been on the rise in America since the outbreak of the financial crisis, and that China had been the “biggest victim” of America’s “misuse” of trade-remedy measures. Both countries have imposed anti-dumping tariffs on some of each other’s products in recent months. American impatience with China’s reluctance to let its currency appreciate has also been growing. Chinese bitterness over arms sales could complicate efforts to resolve such spats.

Having restored top-level military contacts with America just last year (last severed in 2008 after the Bush administration announced arms sales to Taiwan), China is likely to shun the Pentagon again at least for a few months. A planned trip by America’s defence secretary, Robert Gates, to Beijing may be one casualty. But it is less likely that Mr Hu will abandon his plans for a trip to Washington this year. China’s leaders have long felt they have more to gain politically at home by showing off the diplomatic respect they receive from Americans than they have by shunning them.

The Iran conundrum

Once the quarrel over the Taiwanese weapons dies down, the next big collision in geopolitics is likely to be over Iran. Indeed, one reading of the timing of the Taiwan deal is that America intended to show its annoyance over China’s reluctance to join the rest of the members of the UN Security Council and Germany in imposing new economic sanctions on Iran. Now that the deadline Mr Obama set for talking round the ayatollahs has expired, Iran is certainly one of America’s main foreign-policy worries. But the notion that America was punishing China by way of Taiwan looks wide of the mark. If anything, the administration appears to have been eager to avoid forging any linkage between Iran and Taiwan in Chinese eyes.

It is true that China is now the odd man out on Iran in the Security Council. But that, says Nina Hachigian of the Centre for American Progress, a think-tank close to the Obama administration, is because Russia has become more alarmed by Iran and co-operative with the West, rather than because China has changed its own stance. More to the point, America may not yet have given up on the possibility of China playing a constructive role in dissuading Iran from seeking nuclear weapons.

In a speech in Paris on the day of the Taiwan announcement, Hillary Clinton, America’s secretary of state, said she understood why China hesitated to impose sanctions on one of its main energy providers, but urged it to think about the destabilising “longer-term implications” of a nuclear-armed Iran. Given how much oil the Chinese import from Iran, and their appetite for investment in Iran’s energy riches, China is not expected to support strong sanctions. But nor will it necessarily do more than abstain when the Security Council votes—and, with careful handling, it may co-operate on other points.

In some ways, the new friction in relations between America and China is remarkable only for taking so long to make itself felt. Kenneth Lieberthal, director of the Brookings Institution’s China Centre in Washington, says that Chinese-American relations are typically prone to be testy in the first year of a new administration, as the two countries gauge each other’s mettle. Mr Obama’s conscious decision to postpone inevitable irritants such as differences over Taiwan, the Dalai Lama and Iran made for some cordiality, but still disputes occurred. The coming year, Mr Lieberthal says, will be a trying one.

Beyond that, nothing is certain. American officials keep saying that they are keen to build a more “mature” and “strategic” relationship with China, one better able to withstand the inevitable periodic fallings-out. But the relative balance of power between America and China is changing in some nerve-jangling ways—as are the internal politics of China itself. After a decade in power, Mr Hu will step down as party chief in 2012 and as president the following year. Succession uncertainties, as the Taiwan Strait crisis of 1996 demonstrated, can lead to unpredictable behaviour among Chinese leaders. If China misjudges its own strength and underestimates America’s, such unpredictability could become especially dangerous.