A shambles on which the sun never sets: how the world sees Brexit

Rapt observers around the globe are confused, amused and saddened by a crisis that has torn Britain’s reputation for stability to shreds

by Jon Henley and Guardian correspondents

ANew York Times columnist believes the UK “has gone mad”. How, asks a Russian TV host, can Britain fail so spectacularly “to correlate its capabilities with reality”? For Australia, it’s like “watching a loved grandparent in physical and mental decline”.

From China to Israel and Russia to Brazil, a world well beyond Europe is watching Britain’s Brexit bedlam with sorrow, bafflement and amusement – and, in those parts of the globe once told that Rule Britannia meant order, stability and shared long-term prosperity, not a little schadenfreude.

“If you can’t take a joke you shouldn’t come to London right now, because there is political farce everywhere,” wrote the New York Times commentator Thomas Friedman. “In truth, though, it’s not very funny. It’s actually tragic.”

Here was a country “determined to commit economic suicide but unable even to agree on how to kill itself”, led by “a ship of fools” unwilling to “compromise with one another and with reality”. The result was an “epic failure of political leadership”, Friedland said: scary stuff, but “you can’t fix stupid”.

Besides questioning the UK’s collective mental stability, US commentators have seen Brexit as the last act in Britain’s decline from imperial hubris to laughing stock – and rejoiced that there is at least one western nation more at sea than Trump’s America.

The Washington Post’s Fareed Zakaria said in a piece titled “Brexit will mark the end of Britain’s role as a great power” that the UK, “famous for its prudence, propriety and punctuality, is suddenly looking like a banana republic” – and its implosion might even be the beginning of the end of “the west, as a political and strategic entity”.

Brexit plainly looks bad even from places with significant problems of their own. The BBC’s security correspondent, Frank Gardner, recently reported that his office had received an email from someone in Afghanistan saying: “Hope all is OK there in the UK with Brexit, wishing you luck.”

Given the “unbelievable mess that the UK has got itself into”, Israelis should perhaps “avoid wishing ourselves ‘the best of British luck’” ahead of elections this month, declared Susan Hattis Rolef in the Jerusalem Post. All in all, “Britain seems to be short of luck at the moment.”

Even the foreign minister of Venezuela, in the midst of a devastating political and socio-economic crisis, said the British government had been “unable to meet its obligations”. The country needed leadership that, rather than intervening abroad, “takes care of the most felt necessities of the country and distances itself from political chaos”, Jorge Arreaza tweeted.

In Britain’s former colonies, there has been amusement – “I am an Indian, and I can tell you that Brits take forever to leave,” tweeted researcher Deepak Saxena – but also incomprehension at such chaos and division in a supposed model of democracy.

For Kolkata’s Telegraph, not only had Brexit dented Britain’s international image, “the loss of respectability of institutions integral to a democratic set-up” risked damaging the credibility of parliamentary democracy itself.

“How could a modern, educated and open society … have got it so wrong?” asked Subir Roy in an editorial in the Hindu. The answer, he said, was that Britons “were deluded by their popular, lowbrow, chauvinistic, rightwing press”.

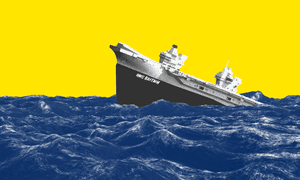

Sreeram Chaulia, dean of the Jindal School of International Affairs, said many Indians saw Brexit as the latest chapter in a “sharp decline in the place Britain commands as a great power”. The UK “is not a gold standard to look up to”, he said. “We get a feeling of a sinking ship, and everybody wants to leave a sinking ship.”

Australia, likewise, has watched the ongoing Brexit omnishambles closely. The two countries share more than historical ties: more British expatriates live in Australia than in any other country, and the EU is Australia’s second largest trading partner.

So observing the UK’s present predicament has been rather like watching the decline of an ageing relative, wrote the ABC’s Nick Rowley: “You care for them deeply. You appreciate all they have done for you. But each day they become more inwardly focused. Their world contracts. They seem increasingly incoherent.”

Cartoonists have skewered Brexit, depicting the UK government as Goldilocks rejecting one Brexit as too hot and another as too cold, or the country as a fish about to be thrown out of the EU tank and on to the chopping board.

Some of this is Australia – with five prime ministers in the past eight years – trying to feel better about itself. But there is genuine shock and sadness, too, for what Brexit will mean for Britain’s standing in the world.

To see a country “deliberately throwing away a close, mutually beneficial partnership, wilfully damaging its economy and influence on a point of cultural principle … was a surprise”, wrote Nick Miller of the Sydney Morning Herald and the Age.

In Hong Kong, Claudia Mo, a pro-democracy MP, told AFP she “used to think the Brits were a very sensible people”. But, she added: “As a former colonial person, it’s almost like a farce. It’s sadly funny, sadly amusing. I’m baffled as to why and how things got to where they are now.”

The Daily Maverick, a South African news website, compared the Brexit saga to a Gilbert and Sullivan light opera – although perhaps “not so likely to end the way they do, with everything nicely and tidily resolved in the last few minutes”.

Outside the EU, wrote commentator J Brooks Spector, “Britain shrinks to a sort of economic ‘Middling Britain’, useful for some great shopping and often great theatre, but not to be seen as a serious global player any more.

“Even if the country is ultimately able to cobble together some kind of new economic relationship with the EU, the international reputation of its prowess as a negotiator would seem to be fatally compromised.”

Other African commentators had some advice for the former imperial masters. “Dear Britain, have you ever heard of project management?” asked Adema Sangale in Kenya’s the Nation. “This discipline refers to when you set yourself a goal and clear milestones and tasks towards achieving it.”

Beyond Britain’s former empire, reactions have been just as forthright. After the 2016 Brexit referendum, Russia’s most recognisable television host, Dmitry Kiselyov, enthusiastically hailed a result delivered by “the bold British”.

Now even the veteran propagandist is looking a bit bored, barely needing to twist the facts to achieve his main goal: making the UK appear a complete basket case. “Our ideas of a certain civilised way of doing business in the west are once again being challenged,” he said last month.

“Everything that’s happening testifies to the irresponsibility of the British elite, their inability to correlate Britain’s capabilities with its reality, its ideas about the world with what its people want, and simply to answer our modern challenges.”

In China, where the British prime minister is referred to affectionately as “Auntie May”, her struggles have inspired some sympathy. On the microblog Weibo, one commenter said: “This is like a soap opera that never ends.” “It must be hard for Auntie May,” another said.

Other Weibo users questioned the merits of democracy. “A country’s people votes and decides, and they kill themselves,” one wrote. “A second people’s referendum is not allowed because it violates ‘democracy’, yet May’s shit Brexit agreement is repeatedly submitted to parliament. Is this democracy?” added another.

Chinese officials have stayed quiet on the topic but state media have weighed in, with the Global Times advising the UK to join China’s Belt and Road initiative, to which few western countries have signed up, as a way to “help bind the Brexit wounds that plague the hearts and minds of British people”.

In an interview with the Global Times, Cui Hongjian of the China Institute of International Studies blamed Brexit on the UK’s inability to deal with globalisation: “Moreover, there are the interests of various political elites which means Brexit has become a farce that won’t end for a long time.”

While Japan’s companies rethink their investments in the UK, the country’s media are increasingly aghast at the uncertainty surrounding Brexit. The Nikkei business paper urged MPs to “quickly put a stop to their endless – and fruitless – arguing”.

The paper added: “It is time for the UK to stop its indecisive politics, with lawmakers seeming as though they are asking for the impossible. The current quagmire can be seen as a test of the wisdom of a country that can take pride in its centuries-old tradition of parliamentary democracy.”

Many Japanese have never fully digested the referendum result, observing simply: “What a mess.” Others are still asking just one question: “What on earth has happened to Britain?”

Brazilians also struggle to understand how the UK could have ended up in such a mess. “When we see this happening in one of the nations of recognised tradition, public spirit and aversion to authoritarianism and anarchy, it makes you think: the world really is in crisis,” tweeted André Ricardo.

Helio Gurovitz wrote on the G1 website that if no agreement in parliament could be reached, “the tragedy of the UK will enter history as an example of where populist demagogy and narrow nationalism can lead”. A political scientist, Alfredo Valladão, argued that Brexit seems “more and more like a sort of slow-motion suicide”.

Others linked Brexit to the global rise of rightwing populist nationalism, including Brazil’s own far-right president, Jair Bolsonaro. “Democracies are fragile,” tweeted Leandro Fernandes.

Additional reporting by Julian Borger, Michael Safi, Kat