Hue and cry about the Library of Congress acquiring the Twitter archive, dating back to its origins in 2006, has shown that we continue to stubbornly believe two myths about social networking. First, that it is private. Second, that it is trivial.

Social-networking sites seem to have a curiously alcoholic effect on users. We approach cautiously and often cynically, then, as we find friends or followers, we gain enthusiasm, lose inhibition, and start taking risks. Just a few days ago a 22-year-old Australian student was expelled from his political party after he tweeted racist rubbish while watching Obama on local television. One tweet read: “If i wanted to see a monkey on TV id [sic] watch Wildlife Rescue.” He said in his defense that his friends understood what he meant, and his tweets had been taken out of context. Which isn’t particularly reassuring. Of course, he is not alone—there is an enormous amount of racist venom online, much of which, annoyingly, is anonymous. And yet it remains part of who we are—as do those who howl it down. (To all who hide behind code names: stop being cowards. Free speech is one thing; hiding behind a pseudonym to bait, goad, and spew bile is simply gutless.)

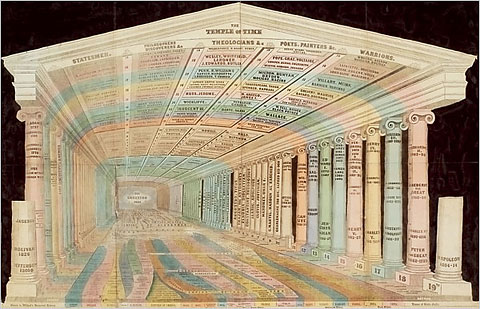

But Twitter is not usually anonymous. It should be obvious enough that if you want to keep something private, you should not tweet or post it in a public forum. Anyone can access it, unless you protect your tweets, and few do. This fact did not stop tweeters from crying—predictably, in these paranoid times—that the library’s decision to store public tweets was a sign of a looming “Big Brother.” Others argued it would be a waste of money to analyze what is commonly dismissed as mindless banter. Yet for historians, tweets would be a great treasure: imagine if the Boston Tea Party protesters had tweeted, or George Washington, or the suffragists. Moses could have tweeted a commandment a day, Babe Ruth between innings, Rosa Parks from her bus seat (or her driver could have!). For decades, historians have been scrambling to find ways that ordinary people thought; in most cases, elites are much better at leaving records behind.

There are 105 million registered users on Twitter, including 200 members of Congress, and 55 million tweets each day. Hourly, there are fierce debates about religion, abortion, politics, health care, the media, and, yes, celebrities, music, and sex. So what would an analysis of these 140-character blurts tell future generations? That we overshare, of course, and stupidly trust the Internet with our most intimate details. That our first use of new technologies tends to show us at our worst, partly because we feel free or somehow protected. It also shows us at our dirtiest. Almost 90 percent of the users of Chatroulette (which enables you to have video chats with random strangers) are men, and one in eight clicks brings up a penis. There’s progress! An RJMetrics study found that you are twice as likely to see a sign requesting female nudity on Chatroulette as you are to actually see it. So the more we advance, the more we … want to see boobs. Does this mean we are more narcissistic and perverted than any other generation? No, we simply have new modes of expression. Millions of tweets are funny, insightful, and clever. The famous are unedited and unguarded: pundits and politicians can look like fools; celebrities can be thought-provoking. Which is why Twitter can be addictive. Most tweeters watch other people: 10 percent of users are responsible for 90 percent of activity, and the median number of tweets is one. One study found that 40 percent of tweets are social babble, though that babble would be of intense interest to historians. In fact, many historians specialize in babble. What is banal today is often significant tomorrow: it tells us who, what, and why we loved, hated, cried—and voted. The trivial can show how madness accompanies sense.

Politics and junk, self-aggrandizement and social activism, the phony and the genuine, the mad and the sweet. This is the history we are hammering out, daily, in the online world that we consider ephemeral and intimate and yet that is rapidly becoming more concrete and public. Martha Anderson, head of digital archiving at the Library of Congress, told The American Prospect that her favorite tweet was “Regarding Library of Congress plan to archive tweets, if journalism is 1st draft of history, is #Twitter the doodles in the margins? :)” Which is a great way to put it. Wouldn’t you love to be able to see doodles in the margins of the Constitution? Would we be shocked if we saw sketches of naked ladies? We shouldn’t be.

Julia Baird is the author of Media Tarts: How the Australian Press Frames Female