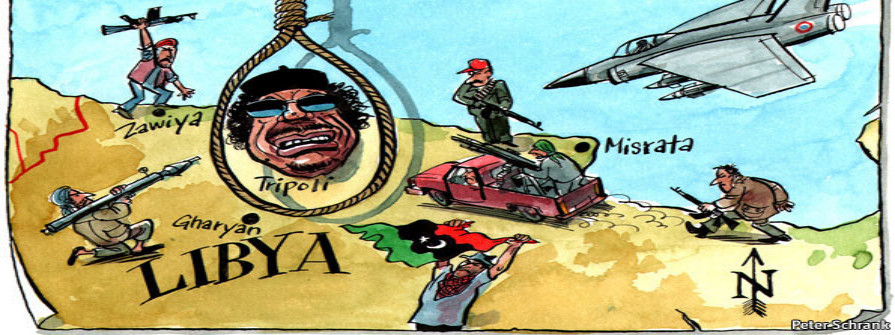

A BLOODY PERIOD OF RETRIBUTION ON LIBYAN HORIZON

The Tunisians are closest to events in the war-torn country on their eastern border. And so it was a clear sign of events to come on Sunday morning when Tunis unexpectedly recognized Libya’s National Transitional Council as the country’s legitimate government.

Up until that point, Tunisia — still reeling from its own recent revolution — had maintained a neutral stance and hosted secret talks between the warring Libyan parties on the island of Djerba.

As rebels appear in control of most of Tripoli, the focus is now on the Transitional Council. The fall of the Gaddafi regime would mean that the Council will assume power in this country of six million inhabitants that did not democratically elect it.

The rebel government in the eastern Libyan revolutionary capital of Benghazi has long been recognized by the US, most European governments, and many fellow Arab countries as the legal representative of the Libyan people. The same holds true for NATO, which is fighting on the rebel side on the basis of what was originally a purely humanitarian United Nations Resolution.

Tribal sheiks and Islamists of all stripes

Neither Libya’s population nor the rebels’ Western partners really know who is pulling the transitional government’s strings. On the outside, at least, former government figures as well as democratic opponents of the regime appear to dominate.

“President” Mustafa Abdul Jalil is a former Justice Minister in the Gaddafi regime who clashed with the dictator on more than one occasion. “Prime Minister” Ahmed Jibril is another former regime member now leading the effort to overthrow it. The other Council front men are civil rights activists and lawyers.

Before the revolution, the man who is now deputy chief of the rebel Council, Abdul Hafiz Ghoga, was a well-known defender of critics and victims of the Gaddafi regime. He was one of the faces of the uprising from the start. Civil rights activists like him automatically assumed leadership roles in Benghazi at the start of a revolution largely organized through Facebook.

The Transitional Council has 40 members. Only 13 of them are known by name — this being, according to the rebels, for “security reasons.” Not all of them are going to be democratically inclined politicians like Ghoga. In Libya, where the Gaddafi government basically dismantled the traditional institutions of government, tribes are very important and some of the anonymous members of the Council are without doubt tribal sheiks.

Islamists of all stripes will also have their place. Although Gaddafi moved against fundamentalists, there was an Islamist underground in Libya made up of former fighters from the wars in Afghanistan. To force the fundamentalists out of the country, Gaddafi, who has ruled Libya for 42 years, had sent them to the Hindu Kush on an anti-Soviet jihad in the 1980s. Among the jihadists who subsequently returned to Libya, there are some who are said to have links to al-Qaeda. Jihadists are said to be concentrated around the port city of al-Dirna, and because of their combat experience are fighting in the rebels’ front lines.

Democratic timetables, regional differences

Just last month, the Transitional Council had suffered a major setback. The rebel Minister of Defense, Abdul Fatah Younis, who served Gaddafi for decades as Minister of the Interior before going over to the rebel side, was shot — by the rebels. The murder was an indication of just how deep divisions are among opposition forces.

Just who is responsible for the general’s death is still unclear. His son put the blame on Islamists, while rebel president Jalil, following the murder, dissolved the Council’s Executive, which was a kind or transitional cabinet, citing “incompetence.” The body has yet to be completely reconstituted.

Worried about its image, a few days ago the Council came up with a democratic timetable which foresees a move from Benghazi to Tripoli a month after the fall of Gaddafi, a handover of power to a legitimate transitional government, and a call for elections. A constitution is to be drafted and put before Libya’s people for their approval.

The main problem the rebel leaders are going to face is getting moderate supporters of Gaddafi on board. Moussa Ibrahim, Gaddafi’s spokesman, has already warned of a bloody period of retribution. In Benghazi this past spring, the rebels arrested Gaddafi loyalists, but didn’t kill them. However, after six months of civil war and thousands of casualties, it will be a good deal more difficult to keep hostilities in check.

All the more so as there have been very few traditional ties between people living in the east and west of Libya. The west, which was home to the Gaddafi regime, also had stronger government ties during Italian colonization, and tends to look more to the Maghreb — Tunisia, Algeria and Morocco. The east is more influenced by Cairo and the classical Arab world.

Even the south, which is mostly desert, plays its own role: here, ties are more with black Africa than they are with the coast extending more than 1000 km between Tripoli and Benghazi. To keep this lightly connected, tribe-dominated state together is going to be the biggest challenge of all for any government after Gaddafi’s fall.

STAFF