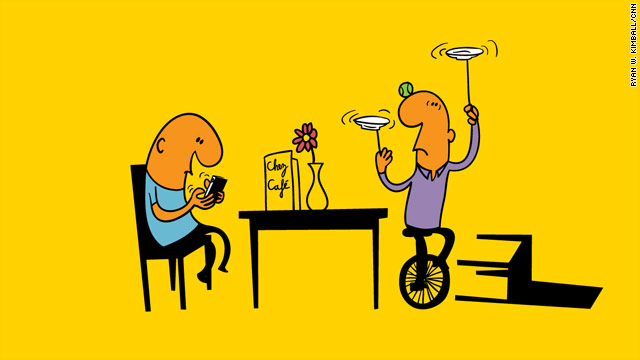

Our fixations on our smartphones are changing social norms, work routines and maybe even how our brains functions

- Smartphones are becoming an important part of life and culture

- Some smartphone owners say they could not possibly be without the devices

- One man uses a Bible app to read scripture to a church congregation

- “If it’s missing on me, I go into a little bit of a panic,” another user says

Doug Wilson takes his smartphone everywhere.

When the 28-year-old wakes up, he snatches the phone from the nightstand to read Twitter feeds and Facebook messages before he gets out of bed.

During the day, he tends to carry the iPhone 4 in his hand. Putting it in his pocket would be too risky, he said, because he might miss a photo opportunity — like that crazy “rat tail” hairdo he saw at a fast-food spot recently. (“I was like, ‘I’ve GOT to take a picture of this!'”)

And at night, access to this on-all-the-time gizmo is arguably more important than ever. First, there’s the dog. Wilson uses his phone’s LED camera flash to guide his steps as he takes Lucy, a bichon frise, outside. “I live in Arkansas, so I don’t want to step on a snake or anything,” he said.

Then there’s his wife, Ashlee, whom he accidentally impregnated one evening after forgetting to look at an iPod app that explains the details of the rhythm method.

“That’s how we got pregnant,” he said, “because I lost my [iPod Touch].”

While the couple from Russellville, Arkansas, are now thrilled about their expected baby girl, Doug Wilson said the slip-up was yet another reminder that his phone should be turned on, in his hand, ready to accept alerts — all the time.

Otherwise, he said, things tend to go awry.

He’s not alone in this hyperconnected world. It seems America is getting hooked on the smartphone. We depend on these modern Swiss Army knives for everything from planning our schedules to checking the news, finding entertainment and managing our social networks. Oh, and they also make calls — a fact that’s sometimes forgotten these days as text messages become a preferred means of communication for younger generations. (Nearly 90 percent of teen cell-phone users send and receive texts, according to the Pew Internet & American Life Project; on average, they send 50 messages per day.)

Only about one in five Americans owns a smartphone, according to a recent report from Forrester Research. But for those who have purchased these devices — which typically cost more than $150 — the experience can be life-changing. Gone are the days when you could wait a full day to reply to an e-mail, or respond to a text message on a several-hour delay, without violating new and rapidly evolving social norms.

Few locations today are off-limits to smartphones. That’s partly because texting, internet browsing and game playing can be done quietly, and because institutions like public schools — once enemies of the phone culture — are starting to embrace these tools.

Some members of the mobile generation love these changes. They say they can’t live without their phones and the always-connected lifestyle they promote. Just try to watch a movie in a theater these days without seeing the glare of a smartphone screen in a nearby seat.

There are serious questions, however, about what these gadgets may be doing to our brains. Some researchers say intense multitasking degrades a person’s ability to focus deeply, think creatively and, in the end, be more productive. Smartphones are among the technologies promoting this mode of thinking, where people toggle continually between streams of information.

A 2009 Stanford University research study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, found that multitaskers — those who try to view two or more types of media simultaneously — are more easily distracted.

“They’re suckers for irrelevancy,” Stanford professor Clifford Nass said in a written statement about the study, which examined 262 university students. “Everything distracts them.”

For these reasons, some people have developed love-hate relationships with their phones. Richard Glover, a 23-year-old political science student at Austin Community College in Austin, Texas, is dependent on his phone, he said, as much as he depends on a car to get him from place to place.

It’s essential that he’s able to check the latest political news all the time, he said, and to be able to respond instantly to text messages.

But in 2008, he took a trip to Yosemite National Park. He couldn’t get cell phone service there, so he left his phone in the hotel room.

“It felt liberating not to be connected to it,” he said, “but at the same time, I was very happy to get back to it — to feel connected again.”

Bud Kleppe, a 32-year-old real estate agent in St. Paul, Minnesota, said he can’t be away from his BlackBerry for any amount of time. He’s more likely to sell a home, he said, if he responds to client e-mails within 20 minutes and to texts instantly.

He likes that feeling of instant connectedness.

“It pretty much lives in my hand,” he said of the phone. “If it’s missing on me, I go into a little bit of a panic. My phone is probably never more than an arm’s grab away from me.”

He says he couldn’t go back to his pre-smartphone existence.

“No, I couldn’t see functioning,” he said. “To me, it’s not a curse. I love it. So I couldn’t — I would probably go into the shakes if I didn’t have it for a day or something.”

Technology won’t stop evolving, so perhaps figuring out how to manage this tech-infused, mobile life may be the way of the future. Kenny Fair, a 60-year-old graphic designer in Overland Park, Kansas, said he’s had to learn to control himself and his gadgets since purchasing a Palm Pre smartphone in August 2009, an event he described as “an immediate love affair” that changed his life.

If he doesn’t manage his smartphone use, he said, he can get lost in the constant “flow of information” from his phone to his head.

Wilson, the smartphone user in Arkansas, said there are moments when he feels as though he disappears into the smartphone’s tiny screen, particularly when he’s just sitting around the house watching TV with his wife.

“I’ll be on my phone looking at Twitter and Facebook and playing ‘Angry Birds’ and I should be showing her affection and stuff like that. Sometimes I forget to do that,” he said.

“I’m just out of touch with reality sometimes because of my phone — I can just look at all the apps and stuff like that and just dream about the iPad and whatever — wishing my screen was bigger — and without realizing it, well, I haven’t said anything to my wife for an hour. It’s not that great.”

Wilson said he’s happy to take his iPhone everywhere.

At Arkansas Tech University, where he’s a student, one sociology professor does not allow phones in his classroom, Wilson said. But instead of leaving his phone at home — one possible way to abide by this rule — Wilson goes through extra preparations to keep it at his side.

“When I go into that class, I put it into airplane mode and silent [mode] and I turn it off,” he said.

He even uses the phone during church services.

Once, when asked to read a scripture in front of the congregation at the West Side Church of Christ, Wilson used a Bible app on his iPhone to load up the correct verses.

“I bought it for like $7,” he said of the app. “It’s really awesome.”

Not everyone at church thought this use of technology was appropriate, he said. Several attendees approached him after the reading, he said, wondering if he was text messaging or something during his performance.

Wilson used to tote around a paper Bible.

But now that book is in the trunk of his car.