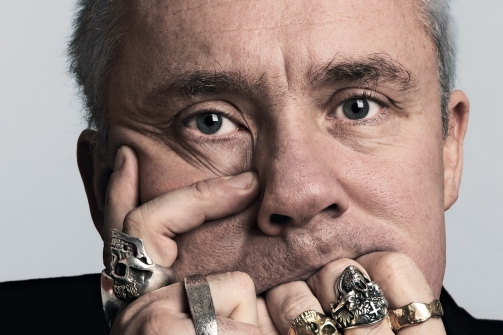

Behind an elegant door on a posh street in London, Damien Hirst, one of the world’s greatest artists, sits surrounded by treasures: an Andy Warhol “Electric Chair” is propped on a shelf; a major Francis Bacon hangs over the room’s mantel; a piece by Jeff Koons sits nearby. That’s as it should be—Hirst is filthy rich and those are his heroes—but what comes as a surprise is all that you expect him to do that he doesn’t: he doesn’t whip out his “willy”; he doesn’t fart or swear (the F word slips out four times, but in Leeds, where he’s from, a vicar would curse more); he doesn’t head-butt me, not even once. Yes, Hirst is dressed all in black and has skull rings on his fingers, but in London that’s the uniform of record producers and restaurateurs. The lout the British tabloids once followed so closely—the “yob” that Hirst says he made sure to be—seems to have disappeared.

“I haven’t had a drink for five years, and I feel great,” Hirst says, comparing that with his wild days in the ’90s. “And a lot of the things where I thought I was feeling great, I look back and I think I was crazy, and pretty volatile.” Hirst now sits demurely in his London business office, speaking with poise and insight. (His home and family are in faraway Devon; his studios, with a staff of almost 200, are scattered across southern England.)

Pop Life: “ ‘Enfant terrible’—I get called that a lot, still, and I’m 47,” Hirst complains. He has three sons, who are 16, 11, and 6, and he’s been with their mother since 1991. Aside from some gray hairs, there aren’t many signs of advancing middle age—except, maybe, that Hirst has agreed to something his younger self had always refused: a full retrospective, launching April 4 at London’s venerable Tate gallery. “Screw that, I’d never show at the Tate,” he says he once insisted to no less a pal than David Bowie. “That’s for dead artists.”

One of those has found a second coming in Hirst. More and more, Hirst’s thriving pop presence and giant market share have left him looking like the single greatest heir to Andy Warhol—and to Warhol’s pioneering collapse of art and artist and price tag into a single “social sculpture,” in the words of the American writer Jack Bankowsky. In 2009, Bankowsky helped put together a Tate show called “Pop Life,” in which he argued that, already in the 1960s, Warhol had made the leap from standard pop art, whose pictures simply showed us our commodified culture, to a new kind of art that combined marketing and buying and selling into part of the artwork itself. On those terms, Warhol’s a tyro compared with Hirst—and Hirst is now at the top of his game.

This could sound absurd, since today’s Hirsts are mostly riffs on objects he came up with two decades ago. By 1992, he’d already floated his famous shark and sheep in formaldehyde, begun his infinite series of spot and spin paintings, and launched into his butterfly collages. Last year, when Hans Ulrich Obrist, codirector of the Serpentine Gallery in London, was asked to select a work for an anthology of the greatest art of the last quarter century, he chose Hirst’s “A Thousand Years,” from way back in 1990. It’s a glass enclosure with a box full of maggots that hatch into flies, feed on a bloody cow’s head, and finally get killed by a bug zapper, and many people name it as the artist’s first masterpiece, and maybe his greatest.

Hirst, Inc.: The thing about such early Hirsts, however, is that they still stand as single works of art in the grand tradition of such things: they were precious objects meant to impress—not much different, in basic function, from any old-master painting or sculpture. They could hardly count as rethinking the nature of art, since they were dedicated to some of the same “timeless” themes as many establishment pictures. Victor Pinchuk, a Ukrainian oligarch who is one of Hirst’s biggest collectors, says he buys the artist for his grandiose subjects. “He is so much about these philosophical questions of life and death?…?More or less the same topic which Michelangelo raised on the Sistine Chapel of the Vatican—about creation and God.” But for Julian Stallabrass, a Courtauld Institute pro-fessor and the smartest of the anti-Hirstians, the “supposedly universal values” that Hirst appeals to are easy and empty clichés. “The surprise is that people haven’t gotten more bored with the objects, considering he keeps repeating them.”

What has happened in the last five years or so, however, is that each of those single pieces has been incorporated into a vast, overarching work of art that could be titled “Damien Hirst, Inc.” His true medium is no longer flies or sharks or spots. His medium is the tabloid press, and the auction market, and his collectors, and his art’s peculiar reception. “I’ve always been aware that the art somehow lies between the Mona Lisa and the postcards of the Mona Lisa. I think Warhol made it fine for artists to deal with all that?…?You’ve got to look at the world the way it is, and just reflect it back to the people who haven’t been born yet. The more you look at the world, the crazier it seems.” In 2007, Hirst created a platinum skull covered in diamonds that he priced at $100 million, and that therefore stood as the perfect symbol of the lunacy of art’s current status. “Money’s not only the key to enable you to make the work, but it’s also the subject as well,” he says. “I’ve said it before: it’s as important as love. And as elusive: I don’t only mean elusive in that you can’t get ahold of it—well, I do—but also to grasp the idea of it, conceptually.” (In fact, when the diamond skull was announced as having fetched its record price, it turned out that Hirst and some pals were the buyers. The giant price tag was a kind of final touch that Hirst added to his own work.) Warhol proposed that the business of art could also be great art. Hirst is Warhol updated for our freewheeling, free-market times.

Cool and Gross: Yet unlike Warhol, Hirst says he’s never put his real self on the line. “I don’t think it’s ever about Damien Hirst. I think that’s an illusion. I remember reading the newspapers and thinking, ‘Well, I’ve got to make art that’s got to operate in this medium’?…?I used to love going to an opening and being out of my mind, and being drunk and falling around and looking like a homeless guy.” He admits he was out to seize column inches: “It’s all about getting an audience.”

Hirst’s most recent audience magnet was last fall’s “Spot” project, which filled all 11 outposts of the worldwide Gagosian Gallery empire with more than 300 polka-dotted canvases, sold alongside spotty Hirst mugs and T-shirts. The project left many critics foaming at the mouth, calling it empty and sold-out. But Hirst feels it was about something peculiar to his situation, “a thing really to do with growth that I’ve been grasping at?…?When I went to the spot show, I thought, ‘S–t. There’s not really any other artist who could do this. And there’s no other gallery, really, that I could do it with.’?” His mega-art and his mega-dealer meshed “in a kind of cool way, but in a gross way as well. But I kind of pervertedly like that.”

Cool and gross—both readings fit the auction that Hirst staged at Sotheby’s in London on Sept. 15, 2008, the very day that Lehman Brothers went bust. Despite that context, more than 200 Hirsts made just for the sale fetched almost $200 million. Yet the auction was less about the objects that sold than it was about itself, as a public performance. “The Gesamtkunstwerk”—the all-encompassing work of art—“was very much a part of it,” says Cheyenne Westphal, who was in charge of the sale for Sotheby’s. (It also didn’t hurt the artist’s bottom line. He’s said to be worth $300 million.) Obrist, the Serpentine curator, notes that no auction except Hirst’s has also become a part of art history, on a par with the paintings and sculptures the discipline normally studies. That is truly redefining what art can be.

P.T. Barnum Redux: Hirst’s background may have uniquely suited him to make that move. Michael Craig-Martin, a conceptual artist who taught him at Goldsmiths College in London, explains that Hirst grew up toward the bottom of the British social ladder, but without ever being part of true working-class culture, with its built-in resistance to all things elite. That left him free to embrace making art, but without being bound by the bourgeois rules of the established art world.

Hirst’s mother, who worked as a florist, “was always drawing us as kids,” he remembers, “and doing paintings of us and paintings of my dad.” Hirst caught her art bug. In high school he would draw pictures, “and people would like them and I’d like that.” Hirst also remembers spending too much time with girls, “and then my male friends would call me gay?…?Being artistic—there’s something not quite macho about it.” He nevertheless found a tiny circle of like-minded peers. “Art filled a void of some kind—it was aspirational, it was visual, it was full of hope and excitement,” remembers Hugh Allan, part of that circle and now a top executive in the Hirst enterprise.

Hirst eventually ended up in a one-year art program. “It was basically to get me off the dole?…?It was almost too much fun to be a career.” But once he was there, his appetite for learning turned out to be voracious. “The Leeds art library had every book in it. And I remember thinking, ‘I’ve got to read everything.’?” (“He’s incredibly well read, Damien, and a very smart man,” confirms Jude Tyrell, a director of his business who’s been with him for 15 years. Like others who are close to Hirst, Tyrell also insists on his extreme generosity. “I’ve lost track of the number of Prada handbags he’s given me,” she says, and lists all the charities he supports.)

Hirst then made it to a squat and a laborer’s job in London, and then finally to Goldsmiths, where he started out making work that Craig-Martin remembers as “much tamer than I was used to from Goldsmiths students. It seemed to refer more to the art-historical past than to his own sense of the present.” Hirst came into his own only in 1988, when he organized Freeze, a pop-up show of fellow students’ work that caused a huge sensation, not only for its daring art (his still-dull sculptures excepted) but also because it broke out of London’s staid gallery system. Hirst always had “a curiosity about the art world itself. Not just about art, but about what surrounds art,” says Craig-Martin. Hirst had taken on the role of artist-impresario, and it’s what his own art has come to be about, as though the Damien Hirst of my visit—the sober thinker and brilliant businessman—were the P.T. Barnum behind a creation named “Damien Hirst.”

“He is what the English call ‘stroppy’ and ‘cheeky.’ By nature he’s a provocateur,” says Craig-Martin, an American expat. “He attracts criticism, but in his very English stroppiness he also provokes it.”

The Unignorable Artist: In London, I gather a trio of younger art-worlders and canvass their take on the artist. At first they all voice huge reservations. “In Britain, in our generation, liking Hirst is probably untenable,” says the 33-year-old artist David Raymond Conroy, “without implying that you’re interested in selling out.” The dealer David Hoyland, who is 34, says that “it’s a great reassurance that [Hirst] has never bought anything from my gallery”—and his tongue is only partly in cheek. Curator Paul Pieroni, 31, goes so far as to insist that Hirst is “the embodiment of everything that’s wrong with contemporary art, across the board?…?He is Thatcher’s child, the essence of neoliberalism that prioritizes the entrepreneurial essence of who you are.”

But then, almost as though their knees have finished jerking, they begin to praise what Hirst has done to change the London scene. Pieroni even admits to having “very warm, runny feelings about early Hirst shows?…?I get a flutter when I think about ‘A Thousand Years.’?” Hoyland, who came to London from Bury in Lancashire, says that “there were no f–king northerners in the art world, and certainly no working-class northerners?…?I don’t think I’d be here without Hirst. I’d be a graphic designer in Leeds or Doncaster.”

Conroy insists that, like it or not, Hirst is simply unignorable. “The business model is what’s interesting,” he says. “The way it deals with the machinations of the market.” He shakes his head, in grudging admiration, over Hirst’s diamond skull: “If you make something that is so s–t, and then sell it to yourself, then it’s interesting.”

Blake Gopnik writes about art and design for Newsweek and The Daily Beast. He previously spent a decade as chief art critic of The Washington Post and before that was an arts editor and critic in Canada. He has a doctorate in art history from Oxford University, and has written on aesthetic topics ranging from Facebook to gastronomy.

As the admin of this website is working, no doubt very soon it

will be renowned, due to its feature contents.

Hi! I just wish to offer you a big thumbs up for your great

information you’ve got here on this post. I will be returning to your

site for more soon.

I almost never leave a response, but i did some searching

and wound up here Damien Hirst: Art and Words From ?Enfant Terrible? | Independent

Research Network. And I do have 2 questions for you if it’s allright.

Could it be only me or does it look like a few of the remarks look

as if they are coming from brain dead individuals?

😛 And, if you are writing on additional social sites, I’d like to follow everything new you have to post.

Could you make a list of the complete urls of your community sites like your linkedin profile,

Facebook page or twitter feed?

I am really loving the theme/design of your web site.

Do you ever run into any internet browser compatibility problems?

A handful of my blog readers have complained about my site not operating correctly

in Explorer but looks great in Firefox. Do you have any solutions to help fix this issue?