There was a time, just a few months ago, when David Cameron was the toast of Brussels. Those who fretted about Britain’s new Conservative prime minister, a declared Eurosceptic, were surprised by how accommodating he could be. He did not stand in the way of the euro zone’s new treaty to create a permanent rescue fund. He even helped to bail out Ireland.

But now that yet another treaty change looms, the old resentment of the perfidious Brits is returning. For many European leaders, it is Britain that stands in the way of their attempt to save their currency from catastrophe. It is not the only problem facing them, of course, but as this column went to press Mr Cameron was set for a hard negotiation at a summit on December 8th-9th.

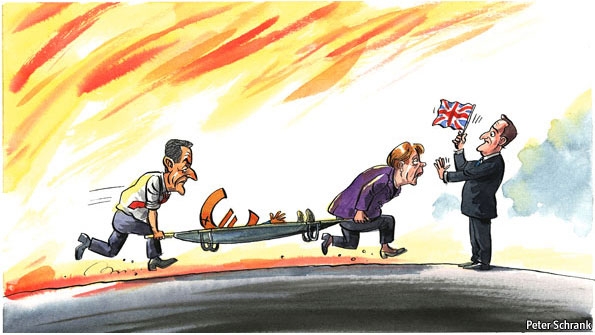

Days earlier in Paris, Nicolas Sarkozy and Angela Merkel, the French president and German chancellor, had all but given Britain an ultimatum: accept their plan to rewrite the laws of the EU, or prompt the 17 members of the euro zone to seek a separate deal and risk British isolation. Mr Cameron said he would veto any treaty that did not contain “safeguards” to protect British interests; if the euro zone wanted a treaty change, so did Britain.

A whiff of Margaret Thatcher and her battles for a budget rebate? The zealots on the Tory backbenches wish it were so. Just as the iron lady wanted her money back, they want Mr Cameron to get some (or all) EU powers back. For them, the prime minister is far too flexible. He has resisted calls for a British referendum. He has said his priority is to find a solution to the euro crisis. And he has given himself lots of room to decide which interests to defend. The EU’s lawyers, moreover, have come up with a partial fix so that changes to governance rules will require only a vote by the 27 leaders, rather than a full revision procedure involving a convention, an inter-governmental conference and ratification in all 27 countries (including some referendums).

British officials like this idea (though their parliament would still have to ratify the changes), but the Germans think it does not provide enough powers to impose fiscal discipline. Yet even if a bust-up can be averted, it would only postpone the reckoning. Slowly or quickly, Britain and the euro zone are moving apart.

EU veterans might see this as just another British spat. Initially excluded from the club by Charles de Gaulle, Britain has been equivocal about European integration ever since it joined in 1973. It got its budget rebate, stayed out of the Schengen free-travel area, opted out of the euro, stayed half-out of co-operation on judicial and police affairs and is blocking attempts to create stronger common defence and foreign policies. Its big reason for sticking with the EU is the single market. This is one area where Britain seeks deeper integration, particularly in freeing up services.

But this crisis really is different. Like the churning of milk to make butter, the financial turmoil is separating Britain from the euro zone. As it forces euro-zone countries to bind closer, the crisis convinces Britons of the wisdom of keeping the pound. Some say Britain would grow faster if it could shed more EU rules. Euro-federalists and Eurosceptics alike feel vindicated: monetary union cannot work without economic and political unity. Under pressure from the markets, leaders are having to address what the French call the finalité politique, the end point: United Nations, or United States of Europe? Nobody will say. Either way, the euro zone is heading for more federalism, and Britain may try to regain more sovereignty.

Mr Sarkozy, in particular, sees an opportunity to turn the euro zone into an exclusive (and perhaps more protectionist) hard core, dominated by France and Germany. There would be ever more summits of the euro members: during the crisis, he wants them monthly. Germany is more careful about ensuring the involvement of EU bodies and the ten non-euro members. But time and again Mrs Merkel has yielded to Mr Sarkozy on the form of “economic government” to try to win tougher controls on national debt and deficits. Whatever the process, the euro zone will be tempted to tamper with the single market. Take the latest German-French missive, on December 7th: it speaks of euro-zone action on financial regulation, labour markets, a financial-transactions tax and the harmonisation of the corporate-tax base. These should all be matters for the EU at 27, not at 17.

What price Britain’s interest?

Britain should worry. Mr Cameron’s price for his assent to treaty change is unclear. Officials speak of changes to EU employment laws; guarantees that EU regulation will not harm Britain’s financial-services industry; mechanisms to ensure that the euro “ins” don’t dominate the “outs”; and preserving the single market.

None of this will be easy. France and others will resist any hint of “social dumping” by Britain. Special pleading for the City of London gets short shrift from those who think “Anglo-Saxon speculators” caused the crisis and may be plotting to destroy the euro. Britain has more support when it seeks to defend the single market and the interests of the euro “outs”. But its friends are wary: if Britain gets special protection for the City, why not extend favours for the car industry in Germany or agriculture in France? And most “outs” do not want to be too closely associated with Britain; their ultimate aim is to become “ins”.

Mr Cameron has to balance aims that may be irreconcilable. In the short term he must avert the collapse of the euro zone and prevent a debilitating mutiny within his own party. This could push him into letting the euro zone go its own way in order to avoid a difficult British ratification. But his longer-term interests suggest he should moderate his bidding to allow treaty change at 27 and remain at the table. Why? To preserve the single market, promote British influence and act as a promoter of economic liberalism—for the sake of Britain and Europe.